Yogshastra

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

This is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Yogashastra" based on the provided Gujarati text. It focuses on the content of the book as presented in the introduction, chapter summaries, and historical context.

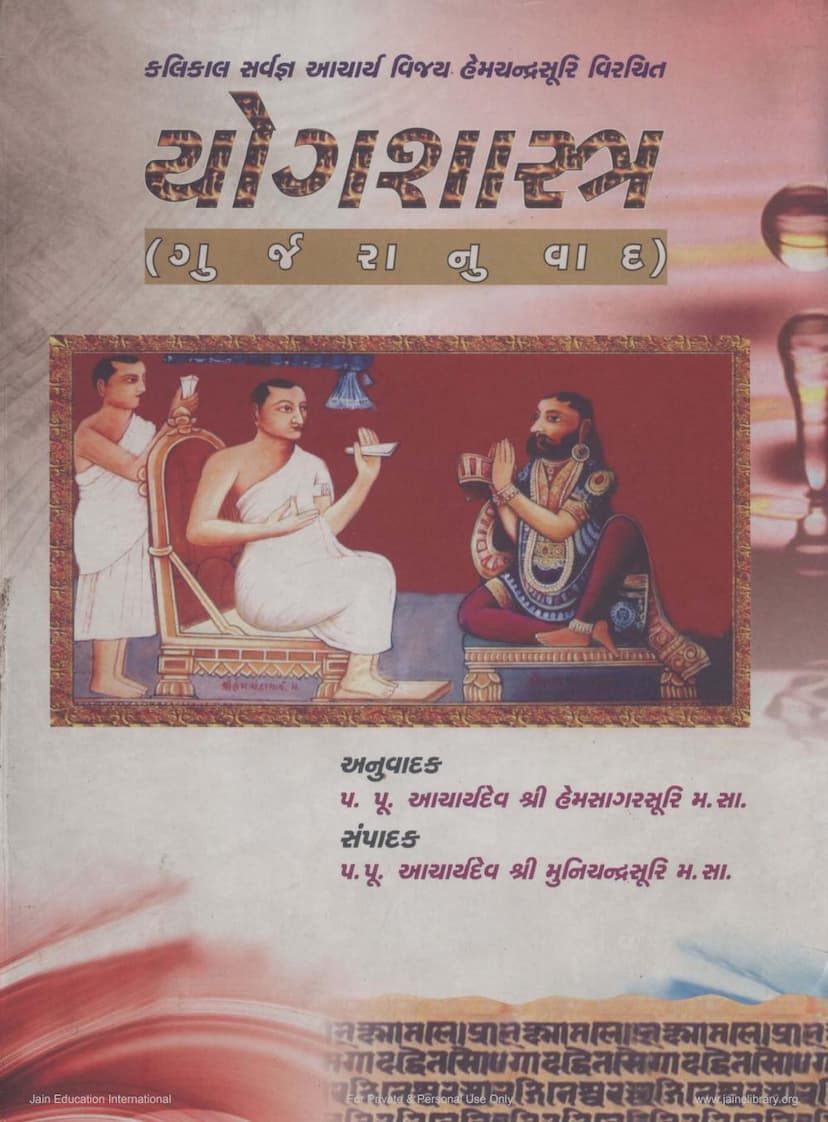

Book Title: Yogashastra Author: Acharya Hemchandracharya (with commentary by Hemchandrasuri, Muni Chandrasuri) Publisher: Omkarsuri Gyanmandir Surat Catalog Link: https://jainqq.org/explore/005118/1

Overview:

The Yogashastra, also known as Adhyatmopanishad, is a seminal Jain philosophical and practical treatise authored by the revered Jain monk and scholar, Acharya Hemchandracharya. It was composed in Sanskrit and later translated into Gujarati. The work is deeply influenced by the spiritual teachings and philosophies of Jainism and is considered a guide to achieving spiritual liberation (moksha) through the practice of Yoga, interpreted within the Jain framework. The book was commissioned by the Chalukya king Kumarpala, who was a devout follower of Jainism and a significant patron of Acharya Hemchandracharya's work.

Authorship and Context:

- Acharya Hemchandracharya: A prominent figure in Jain history, renowned for his vast literary contributions across various subjects, including grammar, philosophy, history, and logic. He lived during the 12th and 13th centuries CE (Vikram Samvat 1145 to 1229). He is famously known as 'Kalikal Sarvajna' (omniscient of the present era).

- Hemchandsuri and Munichandrasuri: These are the translators and editors of the Gujarati version, contributing to its accessibility for a wider audience.

- Publisher: Omkarsuri Gyanmandir Surat, indicating its dissemination within Jain religious and educational circles.

- Historical Patronage: The work was a prayerful request and inspiration from King Kumarpala of Gujarat, who ruled during the late 12th and early 13th centuries CE. Kumarpala's reign was marked by his staunch adherence to Jain principles, including the promotion of non-violence (ahimsa) and the prohibition of animal slaughter, alcohol, and gambling, largely attributed to the influence of Acharya Hemchandracharya.

Structure and Content:

The Yogashastra is structured into twelve 'Prakash' (sections or chapters), comprising approximately 1009 verses in Sanskrit, accompanied by a detailed commentary (svopajnya vivaran) by Acharya Hemchandracharya himself, estimated to be around twelve thousand verses. The book elaborates on the Jain path to liberation, blending philosophical insights with practical guidance.

Key Themes and Content Breakdown by Chapter (Prakash):

-

Chapter 1: Focuses on the auspicious beginning with prayers to Lord Mahavir. It establishes the 'Abhidhey' (subject matter), 'Sambandh' (relation), and 'Prayojan' (purpose) of Yoga. It explains the nature of Yoga through examples of past saints like Dhruvaprahari, Chilatiputra, Emperor Bharat, and Mata Marudevi. It emphasizes that a life not touched by the "stick of Yoga" is futile and likens such a person to an animal. The chapter highlights Moksha as the ultimate goal among the four Purusharthas (Dharma, Artha, Kama, Moksha), with Yoga being its cause. It defines Yoga as the threefold path of Right Knowledge (Samyak Jnana), Right Faith (Samyak Darshan), and Right Conduct (Samyak Charitra). It provides a brief overview of the five Mahavratas (great vows), five Samitis (carefulness in actions), and three Guptis (restraint). It also outlines thirty-five essential qualities required for a householder.

-

Chapter 2: Introduces the twelve vows of a lay follower (Shravak). It begins by explaining the nature of Right Faith (Samyaktva), contrasting it with false faith (Mithyatva), and the characteristics of true deities (Sudev) versus false deities (Kudev), true preceptors (Suguru) versus false preceptors (Kuguru), and true religion (Sudharma) versus false religion (Kudharma). It details the five signs (Chinha) and five ornaments (Bhushan) of Samyaktva, along with five faults (Dushana) to be avoided. The five minor vows (Anuvratas) are then explained:

- Non-violence (Ahimsa Anuvrat): Emphasizes the abandonment of violence through various teachings, condemning those who cause violence. It includes narratives of Subhuma and King Brahmattra who went to hell for causing violence, and the praiseworthy story of Sulsa, the son of a butcher, who renounced violence. It criticizes the creators of scriptures that incite violence and condemns violence in various contexts like hunting, ancestral rites (shraddha), and rituals for divine appeasement or Vedic sacrifices. It praises non-violence and its auspicious fruits.

- Truthfulness (Satya Anuvrat): Explains the importance of truth, detailing the negative consequences of falsehood in this life and the hereafter. It presents the story of Kalkacharya, which yielded auspicious results, and Vasuraja, which led to inauspicious outcomes. It also narrates the story of Kaushik, who spoke truth to inflict pain on others. It condemns speaking falsehood and praises truthfulness.

- Non-stealing (Achaurya Anuvrat): Explains non-stealing, highlighting that theft is considered a graver offense than violence in certain contexts. It tells the story of Mandik the thief, who faced inauspicious results, and Rauhineya the thief, who gave up theft and attained auspicious results.

- Celibacy/Satisfaction with one's own spouse (Swadara Santosh and Paradara Viraman): Discusses the flaws of marital infidelity and lustful desires for others' wives, citing the story of Ravana and the virtuous lay follower Sudarshan Sheth, who renounced extramarital relations. It emphasizes the merits of celibacy and its excellent fruits in this world and the next.

- Non-possession/Limitation of possessions (Parigraha Parimana): Explains the faults of excessive accumulation, referencing stories of Emperor Sagar, Kuchikarna, Merchant Tilak, and King Nanda, and praising the contentment of Abhaykumar, who renounced excessive possessions.

-

Chapter 3: Introduces the three supplementary vows (Gunavratas) for lay followers.

- Restriction on travel (Dik Pariman): This vow is explained first.

- Restriction on indulgence (Bhogopbhog Viraman): This vow is explained in detail, enumerating prohibited items like liquor, meat (detailing its defects and prohibitions), and refuting opposing viewpoints. It also lists forbidden foods like ghee, honey, certain fig fruits, foods with infinite lives (anantkay), unknown fruits, eating at night, raw dairy products mixed with double-sown grains, fruits mixed with insects, and flowers.

- Restriction on purposeless evil (Anarthdand Viraman): This vow involves abstaining from harmful thoughts and actions that lead to suffering, such as those stemming from Arta (afflictive) and Raudra (fierce) meditation, and avoiding harmful advice and various types of negligence. Following the Gunavratas, the four training vows (Shikshavratas) are introduced:

- Samayika: The vow of equanimity or meditation, explaining its nature and the karma-nirjala (shedding of karma) it brings, citing the story of Chandravantam Suk.

- Deshavagashika: The vow of restricting activities to a certain region or time. The story of Chulni's father is mentioned in relation to this vow.

- Paushadh: The vow of observing a day of fasting and spiritual practice, explaining its characteristics and citing the story of Chulni's father.

- Atithisamvibhak: The vow of hospitable charity or giving to deserving guests, illustrated by the story of Sangamaka, who practiced excellent charity. The chapter also explains the transgressions (aticharas) of the twelve vows, advises against fifteen types of karmic trade and business, defines a great lay follower (Mahashravak), and elaborates on seven fields for cultivating good deeds (Jina-bimba, Jina-mandir, Jina-agama, Sadhus, Sadhvis, Shravaks, Shravikas). It refutes Digambara beliefs as inappropriate and explains the daily routine of a Mahashravak, including temple worship, veneration of Jinas, the meaning of various Prakrit mantras (like Ir'yavahi, Namo Arihantanam, Logassa, Siddhanam Buddhanam, Jay Viray, Vandanaka), guru-veneration, duties at dawn and dusk, twenty-five essential practices, thirty-two faults of guru-veneration, dialogues between guru and disciple, thirty-three instances of disrespect, the meaning of 'Pratikraman', the ritual of Kayotsarg (standing meditation), twenty-one faults to avoid during Kayotsarg, and the extensive meaning of 'Pratyakhyan' (renunciation). Finally, it discusses nighttime observances, philosophical reflections on female physical parts from a detached perspective, the steadfastness of vow-keepers illustrated by the story of Kamdev Shravak, contemplation of noble aspirations, the eleven stages (Pratima) of a lay follower, and the story of Anand Shravak in relation to intentional death (Samadhi-maran), praising the path of a lay follower and their superior destination.

-

Chapter 4: Focuses on the internal journey: the unity of the soul with the Triple Jewel (Ratnatrayi), the praise of self-knowledge, the nature of the four passions (Krodha, Mana, Maya, Lobha), victory over passions and senses, the futility of austerities without mental purification, the nature of courtesans, the difficulty of conquering attachment and aversion, and the means to achieve it. It elaborates on the twelve Bhavanas (contemplations): impermanence, loneliness, the body, the influx of karma (Ashrava), the stoppage of karma (Samvara), the shedding of karma (Nirjara), the nature of Dharma, the rarity of obtaining the right path (Bodhi-durlabhata), the structure of the universe (Lok) and the twelve Bhavanas. It describes the fruits of equanimity (Samata-phal) and the nature of meditation (Dhyana), including the four meditations: Maitri (friendliness), Pramod (joy), Karunya (compassion), and Madhyastha (equanimity). It describes the characteristics of a meditating yogi.

-

Chapter 5: Delves into the practical aspects of Yoga, discussing the types of Pranayama (breath control) such as Rechaka (exhalation), Kumbhaka (retention), and Puraka (inhalation), their methods, and their benefits. It explains the nature of Prana and the five types of Vayu (air) – Prana, Apana, Samana, Udana, Vyana – and the fruits of mastering them. It covers the methods and fruits of Dharana (concentration). It describes the movements of Prana (Pavan-cheshta) and the benefits of such knowledge. It details the four Mandal (circles) – Bhauma, etc. – and the four types of Vayu (air) – Purandara, etc., and the application of this knowledge. It covers the fruits of Vayu-knowledge, the nature and fruits of Dharana, the movements of Prana, and the knowledge of Nadis (energy channels). It touches upon Kalan (time) knowledge, determining the time of death through external signs and other indications, dreams, omens, and astrological factors. It discusses knowledge of time of death through external signs, other methods of knowing time of death, dreams, other omens, auspices, hearing sounds, the concept of Shanaishchar Purusha, and relating to birth charts (Lagna), it covers the lords of the Lagna in various zodiac signs. It also discusses knowledge of time of death through machine, knowledge of victory and defeat, and other methods of knowing time of death. It explains the means of fixing Vayu and observing Bindu. It discusses the results of Vedha Vidhi and contemplates Parmkaya Pravesh (transmigration).

-

Chapter 6: Addresses the topic of Parmkaya Pravesh (entering another's body), stating it is ultimately meaningless, and suggests that Pranayama is not the ultimate goal for liberation. It describes the nature and fruits of Pratyahara (withdrawal of senses) and Dharana (concentration).

-

Chapter 7: Outlines the stages for meditation, defining the meditator (Dhyata) and the object of meditation (Dhyeya). It explains the nature of the five types of Dharana: Parthivi (earth), Agneyi (fire), Vayavi (air), Van'i (speech), and Tattvabhu (truth). It highlights the greatness of Pindastha Dhyana (meditation on the body).

-

Chapter 8: Explains the characteristics and fruits of Padastha Dhyana (meditation on syllables or mantras). It describes the nature of Padmayi Devata (deity associated with syllables) and the fruits of meditating on the king of mantras (Mantra Raja). It explains the Padmayi Devata associated with Parmeshthi (the five supreme beings) and its types, along with the fruits of meditating on other mantras.

-

Chapter 9: Focuses on Rupastha Dhyana (meditation on form) and prohibits Ashubha Dhyana (inauspicious meditation).

-

Chapter 10: Discusses Rupatita Dhyana (meditation beyond form), introducing Ajnavichaya, Apayaparichaya, Vipakavichaya, and Samsthanavichaya. It explains the nature of Lokadhyana (worldly meditation) and Dharmadhyana (meditation on righteousness).

-

Chapter 11: Explains Shukladhyana (pure meditation), its qualifications, and four types. It discusses the meditative achievements of Kevalis (omniscient beings) even in the state of Amanaska (mindless). It details the four types of Shukladhyana, the destruction of Ghati (karma that obscures knowledge, etc.), the inherent powers of Tirthankaras, the nature of ordinary Kevalis, Kevalisamudghata (the process of radiating omniscient knowledge), Shaileshikarana (achieving the state of liberation), and the reasons for the upward movement of Siddhatmas (liberated souls).

-

Chapter 12: Contains the exposition of elements realized through experience. It explains the four states of the mind: Vikshipta (distracted), Yadayaata (wandering), Slishtha (attached), and Sulina (pure). It describes Niravalambana Dhyana (meditation without support), the nature of Yoga, and the forms of Bahyātmā (external soul), Antarātmā (internal soul), and Paramātmā (supreme soul). It discusses the unity of the soul and the Supreme Soul, the necessity and quality of a Guru's guidance, the conduct of a yogi according to the Guru's teachings, indifference (Udasinya) and its fruits, the prohibition of sense-control, the means to stabilize the mind, the method of conquering the mind and its fruits, the state of being Amanaska (mindless), and the essence of the teachings. It also reveals the reason behind the creation of the Yogashastra, mentioning the prayer of Maharaj Kumarpal of the Chalukya dynasty.

Historical and Cultural Significance:

- King Kumarpala's Devotion: The Yogashastra served as a crucial text for King Kumarpala, who embraced Jainism under Hemchandracharya's guidance. The text was instrumental in his spiritual development and reign, characterized by adherence to Jain ethics. The king's patronage highlights the profound influence of Jain philosophy on Gujarati society and governance during that era.

- Comparison with Patanjali's Yoga: The text acknowledges the existence of Patanjali's Yoga Sutras and its commentaries, but distinctly presents the Jain perspective on Yoga, emphasizing the Ratnatrayi (Right Faith, Right Knowledge, Right Conduct) as the core of the path to liberation, differing from the Samkhya-Yoga tradition.

- Influence on Jain Literature: The Yogashastra is a significant work in Jain literature, offering a comprehensive approach to spiritual practice that integrates philosophical understanding with ethical conduct. It has been subject to translations and commentaries, further solidifying its importance.

- Enduring Relevance: The emphasis on non-violence, truthfulness, detachment, and spiritual discipline continues to hold relevance in contemporary society, particularly in discussions on ethical living and spiritual well-being. The book's teachings aim to foster personal peace, societal harmony, and ultimately, spiritual liberation.

Summary of the Gujarati Introduction (by Lalchand Bhagwandas Gandhi):

The introduction by Lalchand Bhagwandas Gandhi highlights the profound legacy of Acharya Hemchandracharya, particularly his contributions to Gujarat. It emphasizes the Yogashastra's importance as a guide for both householders and ascetics, and its potential to lead individuals to spiritual liberation. The introduction also mentions various earlier efforts at translating and explaining the Yogashastra, acknowledging the work done by Pandit Kesharvijayji Gani and the Shri Mahavir Jain Vidyalaya. It notes the vastness of Hemchandracharya's commentary, which runs into thousands of verses, and expresses hope that this Gujarati translation will promote the teachings and help alleviate societal ills like violence, dishonesty, and immorality. It also touches upon the current societal issues of increasing violence and the consumption of meat, urging readers to draw inspiration from the Yogashastra to adopt non-violent and ethical practices. The introduction concludes by drawing parallels between the eight limbs of Patanjali's Yoga and Hemchandracharya's explanation of Yamas (ethical restraints) in the context of Mahavratas and Anuvratas.

In essence, Yogashastra by Acharya Hemchandracharya is a profound Jain scripture that provides a detailed exposition of Yoga as a means to achieve spiritual liberation, integrating ethical conduct, philosophical understanding, and practical meditative techniques, all within the framework of Jainism and patronized by King Kumarpala.