Uttaradhyayan Sutram Part 01

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

This document is the first part of the Uttaradhyayan Sutra, covering chapters 1 through 13. It is presented as a commentary and explanation by Acharya Samrat Shri Atmaramji Maharaj, with editing by Acharya Samrat Shri Shivmuni Ji Maharaj.

Here's a breakdown of the content based on the provided pages:

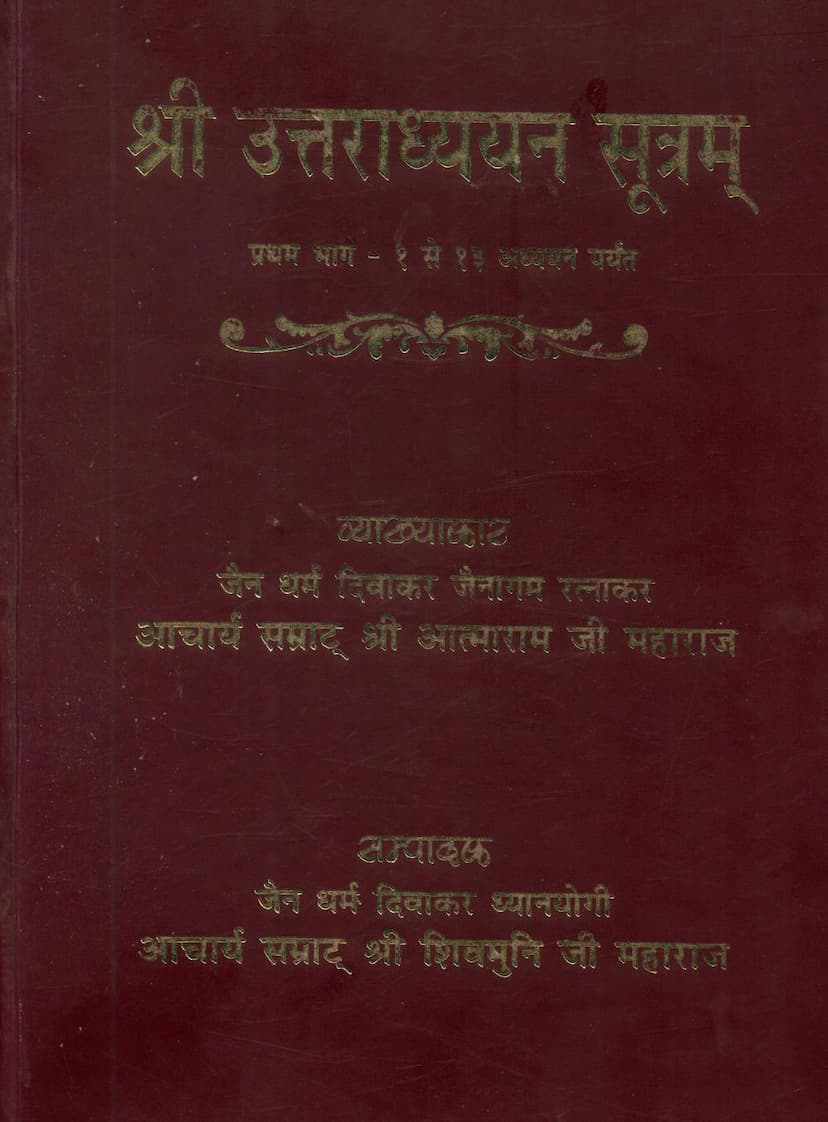

Pages 1-3: Title Page and Publisher Information

- Title: Shri Uttaradhyayan Sutram, Part 1 (Chapters 1-13).

- Author: Jain Dharma Divakar Jainagam Ratnakar Acharya Samrat Shri Atmaramji Maharaj.

- Editor: Jain Dharma Divakar Dhyanyogi Acharya Samrat Shri Shivmuni Ji Maharaj.

- Publisher: Atma-Gyan-Shraman-Shiv Aagam Prakashan Samiti, Ludhiana & Bhagwan Mahavir Meditation and Research Center, Delhi.

- Other Contributors: Guru Shishya Shri Gyanmuni Ji Maharaj (for clarification), Yuva Manish Shri Shirish Muni Ji Maharaj (for cooperation), Bhakt Shri Trilok Chand Ji Jain (Kasoor Wale) family (for financial support).

- Catalog Link: jainqq.org/explore/002202/1 (indicating a digital archive).

- Contact Information: Addresses and phone numbers for the publishing entities.

- Publication Details: Printed in March 2003, priced at three hundred rupees.

Pages 4-6: Publisher's and Editor's Foreword (Prakashkiya & Sampadakiya)

- Significance of Uttaradhyayan Sutra: The text highlights the Uttaradhyayan Sutra as a precious gem in Jain Agam literature, containing profound religious and philosophical teachings through stories, advice, and instructions. It is considered as important in Jainism as the Bhagavad Gita in Vedic tradition, the Bible for Christians, and the Quran for Islam.

- Content: It covers aspects of conduct (achar-vichar), the nature of the soul (atma), the supreme being (paramatma), life, body, and longevity. It emphasizes the importance of humility (vinay) as the foundation for understanding its teachings. The Sutra is described as unfolding countless doors of contemplation, revealing the instability of life and the means to utilize its rare opportunities. The teachings are characterized by their sharpness and heart-touching nature, capable of stirring the reader's life.

- Last Teaching of Lord Mahavir: The Uttaradhyayan Sutra is identified as the final discourse of Lord Mahavir, holding significant importance from this perspective. It comprises 36 chapters, each reflecting on different facets of life and spiritual practice, guiding the seeker on the path to liberation.

- Commentary: The commentary by Acharya Samrat Shri Atmaramji Maharaj is praised for simplifying the profound secrets of the Sutra, making it accessible to the common reader. His teachings are highly sought after, leading to the formation of the publishing committee to expedite the publication of his works.

- Inspiration: The current publication is inspired by Acharya Samrat Shri Shivmuni Ji Maharaj.

- Financial Support: The publication is made possible through the generosity of the family of Shri Trilok Chand Ji Jain.

- Publisher's Commitment: The publishing committee is dedicated to making Acharya Shri Atmaramji Maharaj's literature accessible and believes in achieving their goals with enthusiasm under the guidance of Acharya Shivmuni.

Pages 7-13: Introduction to Acharya Shivmuni Ji Maharaj and Jain Principles (Sampadakiya continued & Specific Sections)

- Acharya Shivmuni Ji Maharaj: He is described as a fearless seeker of the self (nirbhik atmarthi) and a personification of Panchachar (five types of conduct).

- True Strength: The text differentiates between external strength (caste, wealth, friends) and true inner strength (atmabal). It warns against pursuing external strength through unrighteous actions, as it weakens the true self. True strength brings fearlessness.

- Self-Reliance: Lord Mahavir is cited as an example of self-reliance, living fearlessly by relying on his inner strength, not external support.

- The Path of Self-Strength: Developing self-strength requires following the path of truth, non-violence (ahimsa), and spiritual practice (sadhana). This is the path of the brave.

- Asanyam (Lack of Restraint): Defined as excessive attachment to sense objects, leading to attachment to the means of fulfilling those desires (wealth, spouse, status, reputation). The pursuit of these means is called asanyam.

- Sanyam (Restraint): The effort made for controlling the senses and objects of desire.

- The Role of an Acharya: An Acharya is not only a practitioner but also guides others. They identify suitable spiritual paths for their disciples, much like a mother provides food tailored to everyone's needs. An Acharya provides a unifying vision for the community, fostering spiritual growth and purification.

- Panchachar (Fivefold Conduct): The text begins to elaborate on the five pillars of conduct:

- Gyanachar (Conduct of Knowledge): Emphasizes experiential knowledge derived from Jain scriptures, not just theoretical learning. It stresses understanding the essence of the teachings through personal realization and inspiring others. The author's own scholarly background and research in comparative religions are mentioned as contributing to the spread of Gyanachar.

- Darshanachar (Conduct of Perception/Faith): Refers to unwavering faith, devotion, and right perspective. This includes equanimity, inclination towards liberation, detachment amidst worldly engagement, faith in God, Guru, and Dharma, and self-reliance for happiness rather than external sources. It highlights the importance of the soul-view (atm-drishti) over the phenomenal-view (paryay-drishti), as the latter leads to attachment and aversion.

- Charitraachar (Conduct of Righteous Action): Defines charitra as the process of shedding accumulated karma. It leads to transformation and resolution of life's problems. The path of the detached monk (vitaragi muni) is described as one of solitude and happiness. Efforts are made to overcome enemies like anger, pride, deceit, greed, attachment, and aversion.

- Tapachar (Conduct of Austerity): Acharya Shivmuni is described as a secret ascetic, never discussing his austerities. He practices continuous self-study and meditation alongside external fasts. He inspires the community to focus on virtues rather than vices.

- Viryachar (Conduct of Energy/Effort): This involves persistent, attentive effort in self-purification and restraint.

Pages 13-38: Introduction to the Uttaradhyayan Sutra and its Interpretation

- The Nature of Agamas: The text explains the classification of Jain scriptures, mentioning the twelve Angas, twelve Upangas, four Chhedas, and four Moolas, totaling 32 authentic texts after the separation of Drishtivada. It lists the Angas (Achara, Sutrakruta, Sthana, Samavaya, etc.) and Upangas (Aupapatika, etc.).

- Four Anuyogas: The text details the four Anuyogas (streams of discourse) in Jain scripture:

- Charnanuyoga: Pertains to conduct and vows.

- Dharmanuyoga: Deals with religious teachings and narratives.

- Ganitanuyoga: Concerned with mathematics and astronomy (e.g., Suryaprajnapti).

- Dravyanuyoga: Focuses on the analysis and understanding of substances (dravyas), including the lost Drishtivada.

- Hierarchy of Anuyogas: It states that the Anuyogas are progressively more important, with Dravyanuyoga being the most significant, followed by Ganitanuyoga, Dharmanuyoga, and finally Charnanuyoga.

- The Uttaradhyayan Sutra's Place: It reiterates that the Uttaradhyayan Sutra belongs to the Dharmanuyoga category.

- The Meaning of "Uttaradhyayan": The name is analyzed etymologically. "Uttar" can mean 'principal' or 'later.' In the principal sense, it refers to the paramount importance of its religious subject matter. In the sense of 'later,' it signifies its composition after other Angas like Achara, or its current practice after the Dashavaikalika Sutra.

- Structure of Uttaradhyayan: It contains 36 chapters, each dealing with different aspects of life and spiritual discipline.

- Authorship Debate: The text addresses the debate regarding the authorship of some chapters of the Uttaradhyayan Sutra, mentioning that some are considered quotes from the Angas, some are Jin-spoken, and others are attributed to Pratyeka Buddhas or Sthaviras. The commentary by Jinadas Gani Mahattar and Shantisuri aligns with the views of the Niryuktikara (Bhadrabahu Swami).

- Lord Mahavir's Final Discourse: The text strongly supports the view that the Uttaradhyayan Sutra is Lord Mahavir's final discourse, referencing the Kalpa Sutra for corroboration. This point is debated with the Niryukti's mention of contributions from other sources.

- Validation of Lord Mahavir's Teachings: Despite potential influences from earlier traditions, the text emphasizes that Lord Mahavir's teachings were delivered to guide the world. The presence of "iti Vemi" (I say so) at the end of chapters is cited as proof of their direct origin from Lord Mahavir.

- The Importance of Shrut (Scriptural Knowledge): Shrut knowledge is highly valued for illuminating both the inner and outer worlds and for purifying the soul from karma.

- Influence on Buddhism: The text notes the influence of Uttaradhyayan Sutra's teachings on Buddhist scriptures like the Dhammapada, with many verses being directly or indirectly adopted.

- The meaning of "Adhyayan": This is explored in depth, linking it to contemplation of the self (adhyatma), the shedding of karma (apachay), and the path to liberation. It emphasizes Bhavadhyayan (meditation on the self) as the ultimate goal.

- Types of Sutras: The text defines Sutras as concise texts with profound meanings, comparing them to threads that hold together many ideas. It outlines four types of Sutras based on their content: Samjna (name/definition), Karaka (action/rule), and Prakarana (topic-based). It also discusses categories like Utsarga (general rule) and Apavada (exception).

- Reading Methodology: The importance of proper pronunciation (ghosh-sanyog), intonation (udatta, anudatta, svarita), and understanding the meaning is stressed. The six methods of commentary are listed: Samhita, Pada, Padartha, Pad-Vigrah, Chalana, and Pratyavasyan.

- The Goal of Shrut: The ultimate aim of studying scriptures is to achieve self-purification and liberation, not merely intellectual accumulation.

Pages 61-117: Chapter 1 - Vinayashrut (Humility/Discipline)

- Introduction: Begins with the importance of detachment from worldly possessions and relationships for an ascetic (anagar bhikshu).

- Definition of Unagars/Bhikshu: Explains these terms in a spiritual context, signifying detachment from both physical homes (dravya-agar) and mental afflictions (bhava-agar).

- Vinay (Humility/Discipline): The core theme. It's defined by obedience to gurus, attentiveness to their subtle cues (ingita-akar), and selfless service.

- Types of Vinay: Briefly mentions five types: Lokopachar (worldly courtesy), Arth (materialistic), Bhay (fear-based), Kaam (desire-based), and Moksha (spiritual). The focus is on Moksha-vinay.

- Avinay (Lack of Humility): Contrasted with vinay, it describes the behavior of the undisciplined student who disobeys gurus, acts against their will, is resentful, and lacks true understanding. Examples of negative consequences are given, comparing such individuals to dogs cast out from homes.

- The Analogy of the Pig: The text uses the analogy of a pig wallowing in filth, contrasting it with the seeker of knowledge who avoids negative influences.

- The Analogy of the Pig and the Dog: The text likens an undisciplined student to a pig wallowing in filth and a dog with decaying ears being cast out. This highlights how such behavior leads to rejection and suffering.

- Consequences of Avinay: The text emphasizes that undisciplined actions lead to exclusion and suffering, likening the undisciplined student to a pig wallowing in filth or a dog with decaying ears being cast out.

- The Importance of Self-Control: The text stresses the need for self-control, particularly over anger, pride, deceit, and greed, which are seen as internal enemies.

- The Path of the Wise: The wise student learns from gurus, practices patience, avoids associating with the wicked, and focuses on beneficial teachings.

- The Nature of True Knowledge: True knowledge (shruta) is learned from a guru and leads to self-reflection and spiritual growth. It's not about mere bookish knowledge.

- The Practice of Discipline: The student should listen attentively, remain calm, learn from their elders, and avoid meaningless conversations.

- Avoiding Negative Influences: Associating with the corrupt and engaging in frivolous activities are discouraged.

- Controlling Desires: The text advises against excessive attachment to worldly pleasures and the acquisition of wealth, emphasizing the transient nature of these pursuits.

- The Practice of Detachment: The ideal disciple remains detached from sensory pleasures and internal afflictions, focusing on spiritual growth.

- The Analogy of the Horse: The analogy of a well-trained horse vs. an unruly horse is used to illustrate the difference between a disciplined and undisciplined student, and how each is handled by their master.

- The Impact of Actions: The text concludes the first chapter by stressing that a disciplined student gains respect and spiritual progress, while undisciplined behavior leads to ruin.

Pages 110-158: Chapter 2 - Parishaha (Endurances/Trials)

- Introduction to Parishaha: This chapter begins after the discussion on Vinay, addressing the necessity of enduring trials and hardships while practicing spiritual discipline. It establishes the importance of understanding and preparing for these challenges.

- Number of Parishaha: The text states there are 22 types of Parishaha, as expounded by Lord Mahavir.

- The Purpose of Parishaha: These are presented as tests of one's commitment to the spiritual path. A monk who hears, knows, understands, overcomes, and remains steadfast when faced with these during their begging rounds (bhikshacharyā) will not fall from the path of restraint (sanyam).

- The List of 22 Parishaha: The chapters enumerates the 22 types of Parishaha:

- Kshudha (Hunger): Enduring hunger.

- Pipasa (Thirst): Enduring thirst.

- Sheet (Cold): Enduring cold.

- Usana (Heat): Enduring heat.

- Dansha-Mashak (Bites and Stings): Enduring bites from insects and animals.

- Achaila (Nudity/Lack of Clothing): Enduring the lack of clothing.

- Arati (Discomfort/Aversion): Enduring mental discomfort or aversion.

- Stri (Women/Attachment to the opposite sex): Enduring temptations related to women.

- Charya (Wandering/Movement): Enduring hardship during wandering for alms.

- Naishedhika (Sitting/Rest): Enduring discomfort while sitting or resting.

- Shayya (Bed/Comfort): Enduring uncomfortable sleeping arrangements.

- Akrosha (Abuse/Verbal Attack): Enduring harsh words or insults.

- Badha (Physical Suffering/Pain): Enduring physical pain or affliction.

- Yachana (Begging/Asking): Enduring the humiliation or difficulty of begging.

- Alabha (Non-acquiring/Lack): Enduring the failure to obtain desired alms or necessities.

- Roga (Illness): Enduring disease and sickness.

- Trana-Sparsha (Touch of Grass/Thorns): Enduring the discomfort of touching sharp objects or rough surfaces.

- Mala (Dirt/Filth): Enduring bodily filth or uncleanliness.

- Satkara-Puraskara (Honor and Respect): Enduring the lack of honor or respect, or indifferent treatment.

- Prajna (Knowledge/Wisety): Enduring intellectual challenges or the inability to recall knowledge.

- Ajnan (Ignorance): Enduring a state of ignorance or lack of understanding.

- Darshana (Perception/Faith): Enduring doubts or challenges to one's faith.

- Emphasis on Endurance: The chapter stresses that a true monk must not be deterred by these trials. They should face them with equanimity and determination, understanding that these are tests of their spiritual commitment.

- Practical Advice: For each Parishaha, the text often provides advice on how to mentally and practically endure them, such as not retaliating against insults, not entertaining lustful thoughts, and finding inner peace.

- The Goal: The ultimate goal is to overcome these trials through patience, fortitude, and unwavering faith, leading to spiritual progress and liberation.

Pages 159-195: Chapter 3 - Chaturangiya (The Four Essential Limbs)

- Introduction: Following the discussion on Parishaha, the chapter highlights the rarity and importance of four essential spiritual elements required for progress.

- The Four Rare Elements:

- Manushyatva (Human Birth): Being born as a human being is considered extremely rare.

- Shruti (Hearing the True Dharma): Even rarer is the opportunity to hear the true teachings of the Jinas.

- Shraddha (Faith/Conviction): Rarer still is developing genuine faith in the Dharma heard.

- Virya (Effort/Energy for Restraint): Rarest of all is the development of the energy and resolve to practice restraint (sanyam) and follow the teachings.

- The Importance of Each Element: The text elaborates on the difficulty of obtaining each of these, emphasizing that their combination is crucial for spiritual advancement.

- The Cycle of Birth and Death: The chapter describes the continuous cycle of birth and death across various species and realms (deva, narak, tiryanch, manushya) driven by karma. It illustrates how impure actions lead to unfavorable rebirths, while virtuous actions lead to better destinies.

- The Rarity of Human Birth: The human birth is particularly highlighted as a precious opportunity for spiritual liberation because it offers the potential for true understanding and practice of Dharma.

- The Four Rare Elements are Interconnected: The text implies that obtaining one without the others is insufficient. True progress requires all four.

- The Path to Liberation: The ultimate aim is to utilize these rare advantages to break free from the cycle of birth and death and attain liberation (moksha).

Pages 179-195: Chapter 4 - Asankshipta (Not Concise/Extensive)

- Theme of Pramada (Carelessness/Negligence): This chapter focuses on the dangers of negligence and the importance of vigilance (apramada) in spiritual practice.

- The Fleeting Nature of Life: Life is compared to a dewdrop on a blade of grass or a leaf falling from a tree, emphasizing its impermanence and the urgency of spiritual practice.

- The Futility of External Factors: External factors like wealth, family, and even external strength cannot protect one from the consequences of their karma or the inevitability of death.

- The Danger of Misplaced Trust: The text warns against trusting in fleeting worldly things or people for salvation. True refuge is in one's own efforts towards spiritual purification.

- Karma and its Consequences: It highlights that actions (karma) have inevitable consequences. One must face the results of their deeds, whether good or bad.

- The Analogy of the Thieves: The text uses analogies to illustrate how ignorance and carelessness lead to spiritual downfall.

- The Importance of Vigilance: The message is clear: seize the moment, practice diligence, and avoid any form of negligence in spiritual pursuits, as the opportunity for human birth and spiritual progress is rare and time-bound.

- Critique of Materialism: The chapter criticizes the pursuit of wealth and worldly pleasures through unrighteous means, warning of dire consequences in the afterlife.

- Self-Mastery: The ultimate victory is over one's own senses and mind (self-control), which is more significant than conquering external enemies.

- The Role of Wisdom and Humility: The text praises those who, despite their knowledge, remain humble and detached, contrasting them with the arrogant and the ignorant.

- The Illusion of Worldly Goods: It emphasizes that worldly possessions, relationships, and even physical strength are transient and cannot offer true protection or lasting happiness.

- The Need for Self-Reliance: True liberation comes from within, through self-discipline and spiritual effort.

Pages 196-251: Chapter 5 - Akammaraniya (Not Dying by Desire/Unwilling Death)

- Introduction: This chapter delves into the concepts of "Akam Maran" (unwilling/accidental death) and "Sakama Maran" (willing/planned death, often associated with spiritual practices likeSallekhana). It contrasts the deaths of the ignorant (bala) with the enlightened (pandita).

- Akama Maran (Unwilling Death): Associated with ignorance, attachment to desires, and negative karma. It leads to suffering and rebirth in lower realms. Examples of consequences for those driven by greed, anger, and delusion are given.

- Sakama Maran (Willing Death/Spiritual Death): Associated with knowledge, detachment, and virtuous practices. This is a conscious, voluntary departure from the physical body, often through ascetic practices, leading to favorable rebirths or liberation. It's a death chosen by the enlightened.

- The Fourfold Conduct: The chapter emphasizes that to achieve Sakama Maran, one must cultivate virtues like knowledge, right perception, right conduct, and right effort (Panchamarg).

- The Analogy of the Goat: A story illustrates how attachment to worldly desires and improper actions leads to suffering and an unwilling death, similar to a goat being prepared for sacrifice.

- Consequences of Ignorance: The text details the suffering experienced by the ignorant (bala) who are driven by sensual desires and harmful actions, leading them to hellish realms.

- The Importance of Knowledge and Detachment: It highlights how knowledge, detachment, and virtuous conduct lead to a peaceful, chosen death and ultimately liberation.

- The Contrast: The chapter constantly contrasts the fate of the ignorant, who suffer unwilling deaths due to their actions, with the enlightened, who consciously embrace their spiritual progression towards liberation.

- The Role of Karma: Karma is presented as the driving force behind the nature of death and subsequent rebirths.

Pages 277-307: Chapter 8 - Kapiliya (Related to Kapila)

- Introduction: This chapter focuses on the virtue of non-attachment (nirlobhta) and uses the story of Muni Harikeshi (initially named Bal, son of Kausalyanagara's King Nami) to illustrate its importance.

- The Story of Nami and Harikeshi: The narrative unfolds the life of Nami, a virtuous king who renounces his kingdom after experiencing detachment. He encounters Muni Harikeshi (initially named Bal), who, after being abandoned by his worldly attachments and subjected to trials, attains spiritual wisdom and becomes a revered Muni. The story highlights Muni Harikeshi's exemplary conduct and the reactions of the worldly to his austerity.

- The Value of Non-Attachment: The narrative emphasizes that true happiness and liberation come from detaching oneself from worldly possessions, relationships, and sensory pleasures.

- The Dangers of Ignorance and Attachment: The story of the ignorant disciples (students of the Brahmin priest) who insult Muni Harikeshi serves as a cautionary tale about the consequences of ignorance and lack of respect for spiritual seekers.

- The Role of Divine Intervention: The intervention of the Yaksha protecting Muni Harikeshi illustrates that those who uphold Dharma often receive divine support.

- The Distinction Between Internal and External: The chapter differentiates between external austerity (vesha) and internal spiritual discipline (bhava), stressing that true spirituality lies in the latter.

- The Nature of True Knowledge: It underscores that genuine wisdom (jnana) leads to detachment and self-realization, not mere intellectual accumulation.

- The Superiority of Self-Control: The text argues that conquering one's own mind and senses is a greater victory than conquering external enemies.

- The Path of the Virtuous: The story of Nami's renunciation and Muni Harikeshi's unwavering conduct illustrates the path of virtue, detachment, and spiritual pursuit as the means to transcend suffering and attain liberation.

- The Illusion of Worldly Pomp: The narrative critiques the pursuit of external grandeur and the illusion of permanence in worldly affairs, contrasting it with the ultimate reality of the soul's spiritual journey.

Pages 347-378: Chapter 10 - Drumapatraka (The Falling Leaf)

- Theme of Impermanence and Non-Primacy: This chapter uses the analogy of a falling leaf to illustrate the impermanence of life and the extreme importance of avoiding even the slightest negligence (pramada) in spiritual practice.

- The Analogy of the Falling Leaf: The falling leaf signifies the inevitable decay and departure from life, serving as a constant reminder of mortality.

- The Urgency of Spiritual Practice: The teachings of Lord Mahavir to Gautam emphasize the need for constant vigilance and immediate engagement in Dharma, as life is transient and opportunities are rare.

- The Danger of Procrastination: The text warns against postponing spiritual duties, as old age or unforeseen circumstances can hinder them.

- The Consequences of Negligence: Negligence leads to suffering, regret, and the loss of precious human life and opportunities for spiritual growth.

- The Importance of Each Moment: Every moment is precious and should be utilized for spiritual endeavors, as there's no guarantee of future time.

- The Rarity of Human Life: The chapter reiterates the rarity of human birth and the preciousness of life, urging constant effort in the right direction.

- The Cycle of Life and its Pitfalls: It describes how life in various realms (hells, animal kingdom, human realm, heavens) is conditioned by karma, and how negligence in human birth leads to further entanglement.

- The Three Rare Opportunities: The chapter emphasizes the difficulty of obtaining:

- Human birth.

- The opportunity to hear the Dharma.

- Faith in the Dharma.

- Effort (Virya) in practicing restraint.

- The Importance of Vigilance: The core message is to remain ever-vigilant, recognizing the impermanence of life and the preciousness of the present moment for spiritual progress.

- The Analogy of the Athlete: The text may draw parallels to athletes who train diligently to prepare for competition, urging the spiritual aspirant to prepare for the "battle" of life with constant vigilance.

Pages 378-407: Chapter 11 - Bahushruta-Puja (Veneration of the Learned)

- Introduction: This chapter follows the emphasis on vigilance by highlighting the importance of venerating the learned (Bahushruta) and respecting their teachings for spiritual progress.

- The Nature of the Learned: It defines a Bahushruta not just by the quantity of scriptures learned, but by their embodiment of virtue, humility, detachment, and self-control. Such individuals are described as calm, respectful, and detached from worldly desires and external validations.

- The Importance of Following Gurus: The text stresses the necessity of respecting and following the guidance of learned gurus (Bahushrut). Their teachings and example are crucial for dispelling ignorance and guiding the disciple towards liberation.

- The Dangers of Ignorance and Arrogance: It contrasts the qualities of the learned with the negative traits of the ignorant (Abahushruta) like pride, anger, greed, and lack of restraint, highlighting how these hinder spiritual progress.

- The Virtues of a Bahushruta: The chapter describes the Bahushruta as someone who remains unaffected by external praise or criticism, practices humility, maintains equanimity, and diligently follows the path of righteousness.

- Analogies for Bahushruta: Several analogies are used to illustrate the stature and qualities of a Bahushruta:

- The Moon: Like the moon among stars, a Bahushruta shines brightly with wisdom.

- The Elephant: Like an elephant that is not deterred by surrounding noise, a Bahushruta remains steadfast in their spiritual practice.

- The Lion: Like a lion that roars fearlessly, a Bahushruta speaks with authority based on their deep scriptural understanding.

- The Ocean: Like the vast and deep ocean, a Bahushruta possesses profound knowledge and profound calm.

- The Lotus: Like a lotus that remains unstained by mud, a Bahushruta remains detached from worldly impurities.

- The Horse: Like a trained horse guided by a skilled rider, a Bahushruta follows the path of Dharma with discipline.

- The Bull: Like a strong bull carrying its load, a Bahushruta bears the weight of their spiritual duties.

- The Sun: Like the sun dispelling darkness, a Bahushruta illuminates the path of Dharma.

- The Outcome of Bahushruta: Veneration of and learning from the Bahushruta leads to spiritual elevation, the attainment of higher realms (like heaven), and ultimately, liberation.

- The Role of Teachers: The text emphasizes the teacher's role in guiding the student, imparting knowledge, and fostering virtues like humility and detachment.

Pages 403-437: Chapter 12 - Harikeshiya (Related to Harikeshi)

- Introduction: This chapter, following the veneration of the learned, delves into the practice of austerity (tapa) and its importance in spiritual progress. It recounts the story of Muni Harikeshi, a great ascetic, to illustrate these principles.

- The Story of Muni Harikeshi: The narrative details the life of Harikeshi, who was born in a low caste but attained high spiritual status through his virtues and austerity. His encounters with Brahmins and his interactions highlight the hypocrisy of superficial rituals versus true inner purity and detachment.

- The Power of Austerity: The story illustrates how rigorous austerity and detachment from desires can lead to spiritual realization and overcome worldly temptations.

- The Nature of True Renunciation: Harikeshi's story shows that true renunciation is not just about external appearance but about internal detachment from desires and ego.

- The Consequences of Desires: The chapter emphasizes how attachment to desires, wealth, and sensory pleasures (like the story of Nami's desires) ultimately leads to suffering and hinders spiritual progress.

- The Importance of Correct Understanding: The interaction between Muni Harikeshi and the Brahmins highlights the difference between superficial religious observance and true spiritual understanding. The Brahmins, proud of their caste and rituals, fail to recognize the Muni's inner purity, while the Yaksha recognizes and respects his qualities.

- Karma and Rebirth: The text touches upon the cyclical nature of birth and death, where actions in this life determine future lives, emphasizing the importance of righteous conduct.

- The Analogy of the Pig and the Leaf: The chapter uses analogies like the falling leaf and the pig to illustrate impermanence and the consequences of worldly attachments.

- The Path of Vigilance: The overarching message is about the rarity of human birth and the critical need for vigilance in spiritual practice to break free from the cycle of suffering.

- The Role of Humility and Detachment: The story of Harikeshi exemplifies how humility and detachment from worldly desires, even in the face of adversity and insults, lead to spiritual strength and respect.

- The Power of Inner Purity: The narrative underscores that true worth lies in inner purity and spiritual discipline, not in external appearances or social status. The Muni's detachment and equanimity in the face of insults and temptations demonstrate the highest form of spiritual conduct.

- The Story of King Nami: The narrative also includes the story of King Nami, who renounced his kingdom for spiritual pursuits, illustrating the path of detachment and the pursuit of higher truth. The dialogue between King Nami and Indra highlights the contrast between worldly attachments and spiritual liberation.

- The Significance of Self-Control: The chapter emphasizes the mastery over the senses and the mind as the key to true spiritual victory.

Overall Theme: The initial chapters of the Uttaradhyayan Sutra, as presented, lay the groundwork for understanding the Jain path to liberation. They emphasize the rarity of human birth, the importance of ethical conduct (vinay), the necessity of enduring hardships (parishaha), the guidance of learned gurus (bahushruta), the pitfalls of negligence (pramada), the contrast between unwilling and willing death (akam-sakama maran), and the ultimate virtue of non-attachment (nirlobhta) and self-control, all exemplified through stories and teachings. The text serves as a comprehensive guide for spiritual seekers, highlighting the practical aspects of living a virtuous life leading to ultimate freedom.