Uttaradhyan Sutrano Ark

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

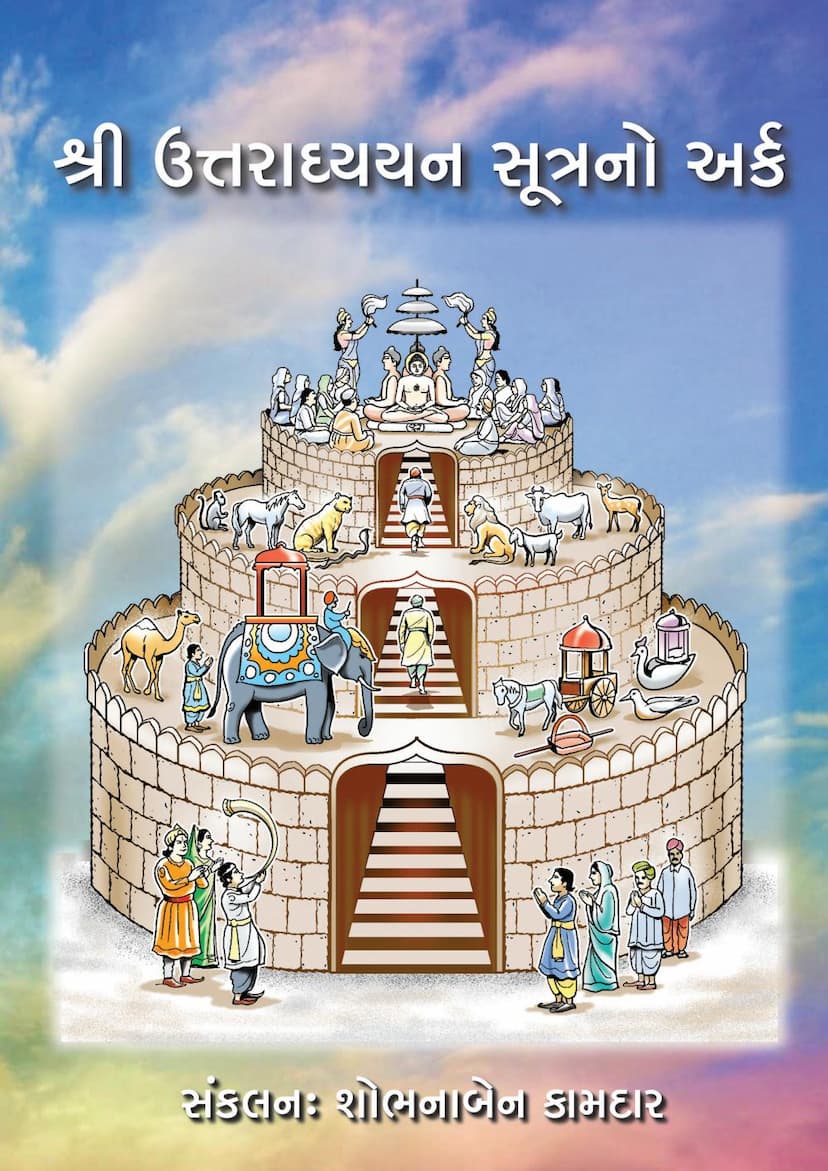

This document is a detailed summary and explanation in English of the Uttaradhyayan Sutra, specifically the Gujarati translation titled "Uttaradhyayan Sutrano Ark" (Essence of Uttaradhyayan Sutra) compiled by Shobhna Kamdar. The book is published by Nima Kamdar.

The summary meticulously outlines the content of each of the 36 chapters (Adhyayans) of the Uttaradhyayan Sutra, providing insights into Jain philosophy, ethics, and practices. Here's a breakdown of the key aspects covered:

Overall Scope:

- The Uttaradhyayan Sutra: It is presented as a treasure trove of Lord Mahavir's teachings, containing the essence of all Jain Agamas. It's a confluence of spiritual, philosophical, and moral life, covering topics like soul and non-soul, karma, six substances (Sad-dravya), nine truths (Nav-tattva), and more. It integrates all four types of Agamas (Anuyogas).

- Compilation: Shobhna Kamdar is praised for her diligent work in distilling the essence of these ancient texts into an accessible format.

- Purpose: The book aims to make the 2000 verses and 36 chapters of the Uttaradhyayan Sutra easily understandable for a modern audience, particularly for children and general readers.

Summary of Key Chapters (Adhyayans):

The summary provides detailed explanations for several chapters, highlighting core Jain teachings:

-

Chapter 1: Vinay Shrut (Importance of Humility and Discipline): This chapter emphasizes the virtue of vinay (humility, discipline, respect) for mendicants. It defines vinay and contrasts the characteristics of a vineet (disciplined one) versus an avineet (undisciplined one). It outlines ten qualities of a vineet, discusses appropriate speech and behavior towards gurus, the importance of self-control, and the duties of gurus towards disciples. It also touches upon ethical guidelines for mendicants, such as avoiding solitary conversations with women and the proper way of accepting alms.

-

Chapter 2: Parishah (Endurance of Hardships): This chapter details the 22 types of parishahs (hardships) that ascetics may encounter in their spiritual journey. It stresses the importance of parishah vijay (conquering hardships) through knowledge and equanimity, rather than succumbing to them. Each of the 22 parishahs is explained with specific examples of how a mendicant should remain steadfast.

-

Chapter 3: Chaturangiya (The Four Essential Elements): This chapter highlights four rare and essential elements for spiritual liberation: human birth, the opportunity to hear the true Dharma, faith in Dharma, and striving for self-control. It elaborates on the cycle of birth and death, the rarity of human birth, the importance of hearing the Dharma, developing faith, and putting in effort for self-control, explaining the results of obtaining these elements and their future implications.

-

Chapter 4: Asanskrut (The Irreversible Nature of Life): This chapter emphasizes the transient and irreversible nature of life, warning against pramada (negligence). It discusses the futility of attachment to wealth and worldly possessions, the inevitability of karma's consequences, and the importance of living a vigilant and disciplined life. It stresses the need to overcome desire, anger, pride, deceit, greed, and carelessness.

-

Chapter 5: Akaam Maraniya (Involuntary Death): This chapter distinguishes between akaam maran (involuntary death, typically due to ignorance or unintentional actions) and saakaam maran (voluntary death, achieved through conscious spiritual practice and equanimity). It describes the consequences of akaam maran, which leads to unfortunate rebirths, and emphasizes the ideal of achieving saakaam maran through spiritual discipline.

-

Chapter 6: Kshullak Nirgathiya (The Ascetic's Detachment): This chapter focuses on the folly of ignorance and the resulting suffering. It highlights that worldly relationships and possessions cannot offer solace during difficult times or in the face of karma's results. It advocates for detachment from worldly connections and material possessions, urging the practice of non-violence and equanimity towards all living beings. It critiques those who rely solely on external appearances or mere rituals without genuine spiritual practice.

-

Chapter 7: Urthiya (The Value of Human Birth and Dharma): This chapter uses various analogies (like goats, coins, and kings) to illustrate that attachment to sensual pleasures and immoral actions leads to hellish realms. It underscores the preciousness of human birth and divine realms, equating the loss of human birth to losing valuable capital. It emphasizes that good deeds and adherence to Dharma lead to favorable outcomes, while the neglect of Dharma results in suffering.

-

Chapter 8: Kapiladiya (The Path to Avoidance of Evil Destinies): This chapter explores how to avoid falling into unfortunate destinies. It stresses the importance of renouncing worldly attachments, controlling the senses, practicing non-violence, and abstaining from greed and sensual indulgence. It highlights the difficulty of renouncing sensory pleasures but illustrates how adhering to great vows can lead to liberation, comparing it to a merchant successfully crossing the sea.

-

Chapter 9: Nami Pravarjya (The Renunciation of King Nami): This chapter recounts the story of King Nami, who renounced his kingdom and worldly pleasures after gaining spiritual insight. It describes his dialogues with Lord Indra, where King Nami intelligently addresses Indra's attempts to dissuom him from asceticism, highlighting the ultimate superiority of spiritual detachment over worldly power and possessions.

-

Chapter 10: Kram Patrak (The Importance of Diligence): This chapter, addressed to Gautama Swami, strongly emphasizes the impermanence of life and the necessity of avoiding pramada (negligence) at every moment. It details the immense difficulty of attaining human birth and the long durations spent in lower life forms, urging constant vigilance in spiritual practice. It highlights the decline of senses with old age and the crucial need for timely spiritual effort.

-

Chapter 11: Bahushrut Mahima (The Glory of Extensive Knowledge): This chapter extols the virtues of a bahushrut (one who possesses extensive scriptural knowledge). It outlines qualities that hinder the acquisition of knowledge (pride, anger, negligence, illness, laziness) and qualities that foster it (humility, self-control, truthfulness, etc.). It contrasts the characteristics of the undisciplined (avineet) and disciplined (vineet) monks, illustrating the immense benefits of scriptural knowledge through various analogies.

-

Chapter 12: Harikeshiya (The Story of Harikeshpal): This chapter narrates the story of Muni Harikeshpal, who was born in a low-caste family but achieved great spiritual stature through his knowledge and conduct. It highlights that true worth lies in one's spiritual attainment (knowledge, conduct) rather than birth or social status, a core tenet of Jainism. It contrasts the violence inherent in rituals like Vedic sacrifices with the non-violent path of asceticism.

-

Chapter 13: Chitra Sambutiya (The Stories of Chitra and Sambhuta): This chapter tells the story of two brothers, Chitra and Sambhuta, who, through jati smaran gnana (knowledge of past lives), recalled their previous births and the consequences of their past actions. It illustrates how past karma influences present circumstances and emphasizes the importance of renouncing worldly attachments and pursuing spiritual liberation.

-

Chapter 14: Ishukariya (The Story of Ishukari): This chapter narrates the story of King Ishukari's sons who, after witnessing the hardships of worldly life and recalling their past lives, renounced their opulent lifestyle to embrace asceticism. It highlights the dialogues between the sons and their father, showcasing the wisdom of renunciation over sensual pleasures and the ultimate goal of eternal happiness through spiritual discipline.

-

Chapter 15: Sabhikshuk (The Ideal Mendicant): This chapter defines the characteristics and conduct of an ideal mendicant (bhikshu). It outlines the virtues of detachment, non-violence, truthfulness, celibacy, non-possession, controlling senses, enduring hardships, and living a life of renunciation and service. It emphasizes that true mendicancy lies not in external attire but in inner transformation and adherence to Jain principles.

-

Chapter 16: Brahmacharya Samadhisthan (States of Tranquility in Celibacy): This chapter details ten specific practices or principles for maintaining celibacy and achieving mental tranquility. These include maintaining a secluded living space, avoiding discussions about women, maintaining distance from women, controlling the gaze, not listening to suggestive sounds, renouncing memories of past sensual experiences, moderate eating, avoiding overindulgence, abstaining from bodily adornment, and controlling all five senses.

-

Chapter 17: Pap Shramaniya (The False Ascetic): This chapter criticizes those who adopt the outward appearance of an ascetic without genuine inner transformation and adherence to principles. It describes various forms of "false asceticism" characterized by negligence, pride, attachment to worldly comforts, lack of discipline, and deviation from prescribed conduct. It warns against the detrimental consequences of such practices in this life and the next.

-

Chapter 18: Sanjaya (King Sanjaya's Path): This chapter recounts the story of King Sanjaya, who, after witnessing the suffering of animals intended for sacrifice, experienced deep remorse and renounced his kingdom to become an ascetic under the guidance of Muni Gardabhali. It highlights the transformative power of spiritual guidance and the pursuit of truth over worldly power. It also mentions the stories of other righteous kings who renounced their kingdoms for spiritual liberation.

-

Chapter 19: Mrigaputra (The Story of Mrigaputra): This chapter tells the story of Mrigaputra, a prince who, upon witnessing the suffering of beings destined for slaughter, gained jati smaran gnana and renounced his worldly life for asceticism. It depicts the poignant farewell to his parents and his firm resolve to endure the hardships of ascetic life, drawing a parallel between his path and that of a deer in the wilderness.

-

Chapter 20: Mahanirgathiya (The Great Renouncer): This chapter discusses the path to moksha (liberation) and Dharma. It begins with King Shrenik's encounter with Muni Anathi, who explains the concept of being 'without a protector' (anath) in the worldly sense, contrasting it with the self-reliance and liberation achieved through spiritual discipline. It emphasizes that the soul itself is the creator of its happiness and suffering and that self-control is the key to liberation.

-

Chapter 21: Samudrapaliya (The Story of Samudrapal): This chapter narrates the story of Samudrapal, a wealthy merchant's son who, after witnessing a condemned man being led to execution, gained insight into karma and its consequences, leading him to renounce his worldly life. It emphasizes the importance of virtuous conduct and detachment for spiritual progress.

-

Chapter 22: Rathnemiya (The Story of Rathnemi): This chapter recounts the story of Prince Rathnemi, who, on his way to his wedding, was deeply moved by the sight of animals destined for sacrifice. This experience led him to renounce his marriage and embrace asceticism. It also highlights the story of Rajamati, Rathnemi's intended bride, who, upon hearing of his renunciation, also chose the path of asceticism. It concludes with the eventual downfall of some Yadavas due to their misconduct.

-

Chapter 23: Keshi Gautamya (The Dialogue between Keshi and Gautama): This chapter features a significant dialogue between Muni Keshi (disciple of Parshvanatha) and Muni Gautama (chief disciple of Mahavir Swami). They discuss the apparent differences in the teachings of their respective Tirthankaras, such as the four great vows (chaturyaam) versus the five great vows (Pancha Mahavrata), and the practice of wearing clothes versus nudity. The dialogue clarifies that these differences arise from the specific needs and understanding of the disciples of each era, with the underlying goal of liberation remaining the same.

-

Chapter 24: Pravachan Mata (The Mothers of Precepts): This chapter introduces the concept of the "Eight Mothers of Precepts," which are the five samitis (careful conduct) and three guptis (restraints). These are considered essential for spiritual practice and are called "mothers" because they nurture and protect the spiritual path. The chapter details each samiti (Eryia, Bhasha, Eshana, Adan-Nikshepa, Pratishthapana) and gupti (Man, Vachana, Kaya) with their respective rules and principles.

-

Chapter 25: Yajniya (The True Sacrifice): This chapter contrasts the external rituals of Vedic sacrifices with the internal purification achieved through true spiritual practice. It highlights that mere outward appearances like tonsure or wearing specific garments do not constitute true asceticism or Brahmanism. True Brahmins are those who embody self-control, detachment, and knowledge, irrespective of their birth.

-

Chapter 26: Samachari (Conduct and Practices): This chapter outlines ten specific rules of conduct (samachari) for mendicants, covering their daily routines, interactions, and practices. These include rules for entering and leaving dwellings, seeking permission from gurus, the proper way to accept alms, performing vavaiyavachcha (service), practicing introspection, and maintaining equanimity in various situations.

-

Chapter 27: Khakiya (The Imperfect Disciple): This chapter discusses the consequences of having imperfect or undisciplined disciples. It uses the analogy of a bad bull in a cart to illustrate how undisciplined disciples can hinder the spiritual progress of their guru and cause disruption. It highlights the challenges faced by a guru with such disciples and the importance of self-discipline for both the guru and the disciple.

-

Chapter 28: Moksha Marga Gati (The Path to Liberation): This chapter elaborates on the means to achieve liberation (moksha). It reiterates the importance of right faith (samyak darshan), right knowledge (samyak gnana), right conduct (samyak charitra), and right austerity (samyak tapa). It delves into the nature of the soul, the six substances (shat dravya), the nine truths (nav tattva), and the process of karma bondage and liberation.

-

Chapter 29: Samyak Parakrama (Right Effort): This chapter lists 73 essential elements for right effort in spiritual practice. These cover various aspects of discipline, devotion, introspection, detachment, self-control, and the ultimate goal of achieving moksha. It elaborates on the benefits of each practice, such as samvega (ardent desire for liberation), nirveda (dispassion), faith in Dharma, serving gurus, confession, self-criticism, repentance, equanimity, and various forms of austerities.

-

Chapter 30: Tapomarga Gati (The Path of Austerity): This chapter provides an in-depth explanation of tapasya (austerity) as a crucial means for spiritual purification and liberation. It categorizes austerity into external (bahya tapas) and internal (aantrik tapas), detailing the various practices within each category, such as fasting, moderation in food, renunciation of desires, physical endurance, and practices like confession, humility, service, study, meditation, and non-attachment.

-

Chapter 31: Charan Vidhi (The Practice of Conduct): This chapter outlines the principles of righteous conduct (charitra) for ascetics. It emphasizes the importance of the five great vows (Pancha Mahavrata), five careful practices (Pancha Samiti), and three restraints (Tri Gupti). It also discusses various ethical considerations, such as controlling desires, avoiding attachments, living austerely, and the progressive stages of spiritual development.

-

Chapter 32: Pramada Sthan (States of Negligence): This chapter focuses on the dangers of negligence (pramada) in spiritual practice and outlines the means to achieve tranquility (samadhi). It highlights the importance of controlled eating, wise companionship, and secluded living. It discusses the origins of suffering in attachment, desire, and ignorance, emphasizing the need to overcome these through self-control and detachment.

-

Chapter 33: Karma Prakriti (Nature of Karmas): This chapter delves into the intricate science of karma, explaining the eight main categories of karmic matter (ashtakarma) and their specific effects on the soul. It describes how karmas are formed through passions (kashayas) and actions (yog), and how different types of karma influence one's destiny, lifespan, physical attributes, and spiritual progress. It details the process of karma bondage and the stages of its fruition.

-

Chapter 34: Leshya (Subtle Dispositions): This chapter explains the concept of leshya, which refers to the subtle mental and emotional states that influence one's karma and destiny. It describes the six types of leshya (Krishna, Neela, Kapota, Tejo, Padma, Shukla), their associated colors, tastes, smells, textures, mental states, and their impact on one's rebirth and experiences. It highlights the importance of cultivating positive leshya to progress spiritually.

-

Chapter 35: Angaar Marga Gati (The Path of the Unattached): This chapter focuses on the path of the angaar (ascetic) who renounces all worldly attachments and follows the principles of Jainism. It details the ascetic's lifestyle, including detachment from family, adherence to the five great vows, the importance of choosing appropriate living spaces, and the ethical considerations regarding food and possessions. It emphasizes the ultimate goal of liberation through steadfast spiritual practice.

-

Chapter 36: Jiv Ajiv Vibhakti (Distinction Between Soul and Non-Soul): This chapter provides a fundamental explanation of the Jain metaphysical principles, distinguishing between the soul (jiv) and non-soul (ajiv). It elaborates on the six substances (shat dravya) of the universe: soul, non-soul, medium of motion (dharma), medium of rest (adharma), space (akash), and matter (pudgal). It describes the characteristics and classifications of each substance, including the different types of souls (mobile and immobile) and the subtle and gross forms of matter. It also outlines the path to liberation through right knowledge, faith, and conduct.

Overall Impression:

The summary indicates that this Gujarati compilation serves as a valuable resource for understanding the profound teachings of the Uttaradhyayan Sutra in a simplified and systematic manner. The introduction by Dr. Ratanben Khimji Chadwa highlights the book's comprehensiveness and its ability to distill complex spiritual concepts into easily digestible lessons.