Tattvopaplavasinha

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Tattvopaplavasimha" by Jayarasi Bhatta, based on the provided text:

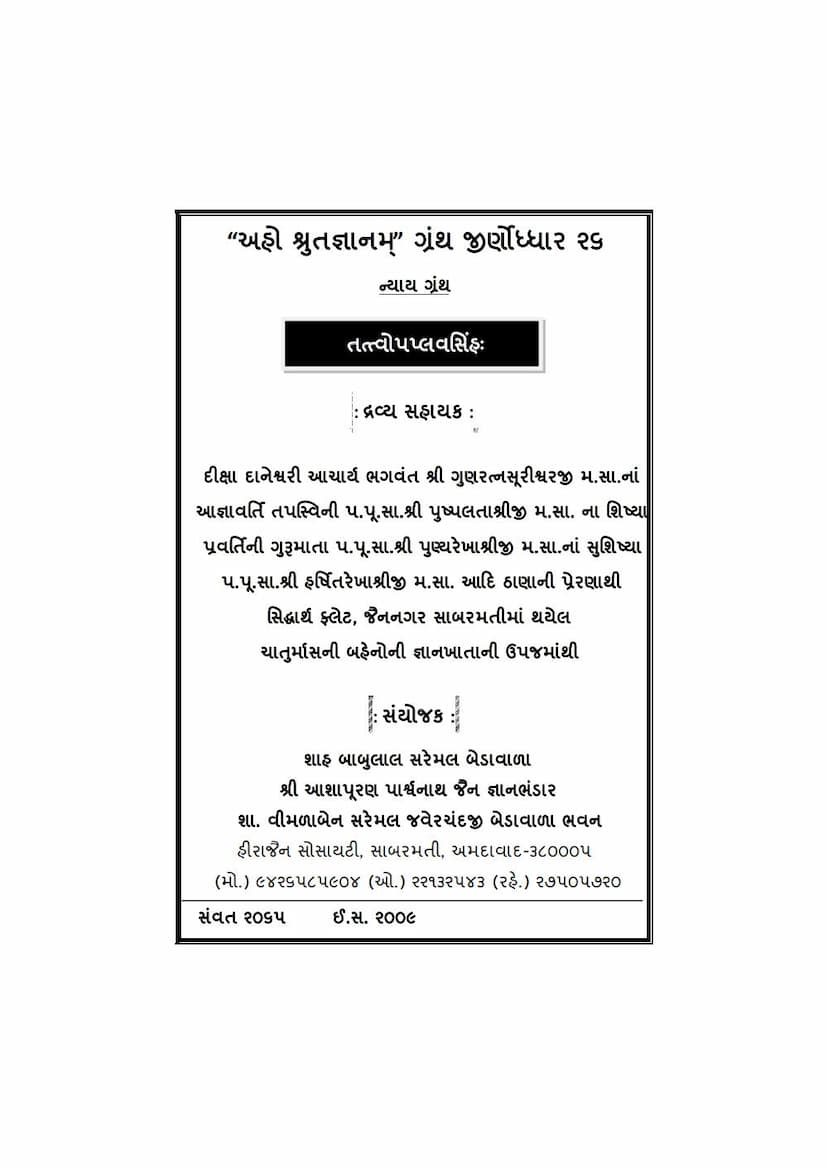

Title: Tattvopaplavasimha (तत्त्वोपप्लवसिंहः) Author: Jayarasi Bhatta (जयराश भट्ट) Editors/Translators: Pandit Sukhlal Sanghavi (पण्डित सुखलाल संघवी), Prof. Rasiklal C. Parikh (प्रो. रसिकलाल सी. पारेख) Publisher: Oriental Institute, Baroda (ओरिएंटल इंस्टीट्यूट, बड़ौदा) Publication Year: 1940

Overview and Significance:

"Tattvopaplavasimha" is a unique and highly significant work in Indian philosophy, primarily known for representing the Lokayata or Charvaka school of thought, specifically a skeptical branch of it. For a long time, the Charvaka school was only known through critiques in other philosophical systems. This work, however, is attributed to the Charvaka school itself, filling a crucial gap in our understanding of this materialist and atheist tradition. The book's title translates to "The Lion that Overthrows Principles," aptly reflecting its radical skeptical stance.

Core Argument and Method:

Jayarasi Bhatta's central argument in "Tattvopaplavasimha" is the refutation of all instruments of valid knowledge (pramanas) as understood by the various established schools of Indian philosophy. His method is rigorously critical, akin to a Kantian critical examination. He systematically analyzes the theories of pramanas proposed by the Nyaya, Mimamsa, Buddhist, Sankhya, and other schools, aiming to demonstrate their inherent contradictions and ultimate untenability.

Key Sections and Critiques:

The work undertakes a detailed critique of various pramanas and related concepts:

- Pratyaksa (Perception): Jayarasi meticulously deconstructs the Nyaya definition of pratyaksa, questioning the validity of terms like "avyabhichari" (non-erroneous) and "vyavasayatmakam" (determinate). He argues that the conditions for valid perception are impossible to meet, highlighting issues with the source of knowledge, the lack of certainty, and the problem of distinguishing between the real and the illusory.

- Anumana (Inference): He challenges the very possibility of inference by scrutinizing the concept of the "invariable connection" (avina'bhāva-sambandha) between the probans (hetu) and the probandum (sadhyā). He points out the difficulty in establishing this connection, especially across different times, places, and causal relationships, and critiques the Buddhist notion of inference based on dependent origination.

- Sabda (Testimony/Verbal Authority): Jayarasi dismisses the validity of testimony, including Vedic authority (apaurusheyatva - being without a human author) and the claims of aptas (authoritative persons). He questions the nature of linguistic meaning, the concept of an invariable relation between word and meaning, and the reliability of verbal testimony in general.

- Arthāpatti (Postulation): He criticizes the Mimamsa concept of arthapatti, arguing that the postulation of unperceived entities to explain perceived phenomena is flawed and lacks proper grounding.

- Upamana (Analogy): The validity of analogy is questioned due to the difficulties in establishing a truly comparable relationship between dissimilar things.

- Abhava (Non-existence): Jayarasi debunks the idea of non-existence as a separate valid means of knowledge, arguing that any knowledge of non-existence must be dependent on prior knowledge of existence or its absence, leading to circularity or ungrounded claims.

- Sambhavā and Aitihya (Possibility and Tradition): These are also critiqued and subsumed within other rejected pramanas, further diminishing the scope of valid knowledge.

Critique of Specific Schools:

Beyond the general refutation of pramanas, Jayarasi engages with specific philosophical doctrines of various schools:

- Nyaya: Detailed criticism of the Nyaya theory of perception and inference.

- Mimamsa: Challenges their understanding of pramana, arthapatti, and the authority of Vedic injunctions.

- Buddhism: Critiques their theories of pratyaksa (especially Kalpana'apodam), anumana, the concept of Skandhas and the denial of an enduring self, and the notion of momentariness (kshānikatva). He particularly targets the Buddhist concept of apoha (exclusion) as a basis for knowledge.

- Sankhya: Critiques their theory of pratyaksa and the concept of purusha and Prakriti, questioning the possibility of the purusha experiencing or being liberated.

- Jainism: Jayarasi refutes the Jain doctrine of anekāntavāda (the doctrine of manifoldness) and the concept of syadvada (conditional predication), arguing against their relativistic epistemology.

- Vedanta: He criticizes the Vedanta concept of ananda-maya Atman (self as bliss) and the idea of liberation (moksha) through knowledge of Brahman.

The Author and the Text:

- Jayarasi Bhatta: The author is identified as a proponent of the Lokayata/Charvaka school. While the exact period of his life is debated, the editors place him between the 8th and 9th centuries CE, based on references in other works. He is believed to have been a Brahmin.

- The Text: The present edition is based on a palm-leaf manuscript discovered in 1926 in Patan. The manuscript dates back to 1292 CE. The text has been critically edited with an introduction, indices of philosophical terms, proper names, and quotations to aid scholarly research. The editors have noted illegible portions and provided emendations.

Conclusion of the Work:

Jayarasi Bhatta concludes that, after this rigorous examination, all valid means of knowledge are ultimately undermined, leading to a state of "tattvopaplava" – the upsetting or dissolution of all principles and reality. This radical skepticism aligns with the core tenets of the Charvaka philosophy as understood in its most extreme form.

Overall Impact:

"Tattvopaplavasimha" is a monumental work of philosophical skepticism. It not only provides a detailed critique of the epistemological frameworks of major Indian philosophical schools but also offers a profound insight into the radical anti-establishment stance of the Charvaka tradition. Its critical method and the depth of its analysis make it a crucial text for understanding the history of Indian philosophy and the challenges posed by skeptical thought.