Tattvarthadhigama Sutra Tika

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the provided Jain text, "Tattvarthadhigama Sutra Tika," authored by Umaswati and commented upon by Dhirajlal D. Mehta, as published by Shri Jinshasan Aradhana Trust. This summary is based on the provided Gujarati text, focusing on its introductory and explanatory sections.

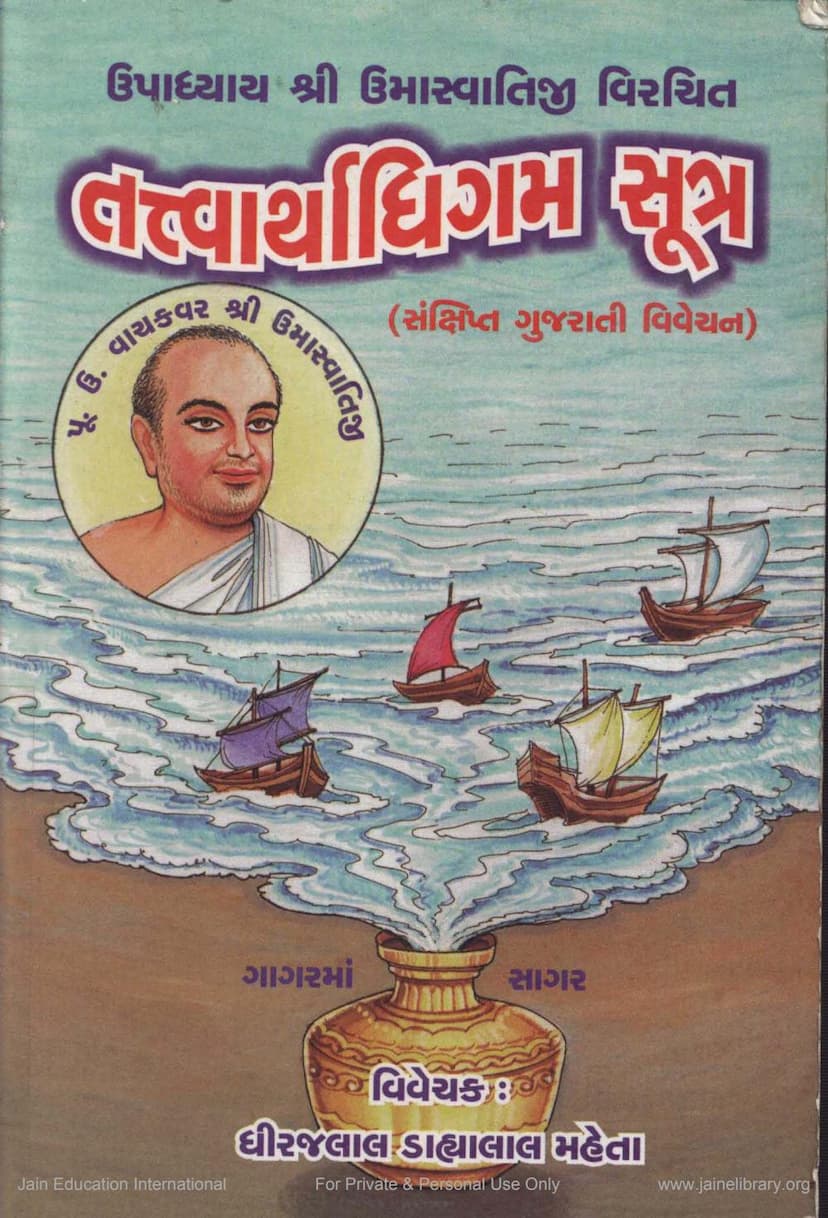

Book Title: Tattvarthadhigama Sutra Tika (A Brief Gujarati Commentary) Original Author: Acharya Umaswati (also known as Umaswami) Commentator/Author of Gujarati Commentary: Dhirajlal Dahyalal Mehta Publisher: Shri Jinshasan Aradhana Trust, Mumbai Manuscript Reference: JainQQ.org Catalog Link Provided

Overall Nature of the Work:

The "Tattvarthadhigama Sutra" is a fundamental and unique text in Jain philosophy, considered seminal by both the Shvetambara and Digambara traditions. It systematically explains the core principles of Jainism. This specific publication is a concise Gujarati commentary on this foundational sutra, making its profound teachings accessible to a wider audience.

Key Aspects of the Commentary and Introduction:

-

Significance of Tattvarthadhigama Sutra:

- It is described as an "original" (maulik) text that explains the principles of Jain philosophy.

- It covers a vast array of essential Jain concepts, including:

- The Nine Tattvas (Navatattva)

- Six Substances (Shatdravya)

- The Three Jewels (Ratnatrayi: Right Faith, Right Knowledge, Right Conduct)

- Karmic literature

- Five States of the Soul (Panch Bhav)

- The soul's passage to the next life (Jiva ka Parabhavagaman)

- The geography of the Jain universe (Jambudweepa and other continents/oceans)

- Deities of the four realms (Chare Nikaya ke Devo)

- Tri-pada (Three entities/aspects)

- Substance, Qualities, and States (Dravya-Guna and Paryaya)

- The Twelve Vows (Dwaadash Vrat) and their transgressions (Atichara)

- The different types of karmic influx (Ashrava) and bondage (Bandha)

- The four types of bondage: Prakriti, Bandha, Adi, and Bandha.

- The sutras are concise (approximately 344 sutras) but carry immense depth and meaning, often implying vast concepts within short phrases.

-

Acceptance Across Jain Traditions:

- The text is uniquely accepted by both the Shvetambara and Digambara traditions.

- While there are minor differences in the numbering of some sutras or the phrasing in some sutras, the core principles are universally recognized.

- There is a slight difference in the pronunciation of the author's name: Digambaras refer to him as "Umaswami," while Shvetambaras use "Umaswati."

-

Author's Affiliation (Umaswati/Umaswami):

- The commentary extensively discusses the scholarly debate regarding whether Acharya Umaswati belonged to the Shvetambara or Digambara tradition.

- Arguments for Shvetambara affiliation are presented with references to prominent Shvetambara scholars (Acharya Yashovijayji, Acharya Atmaramji, Acharya Sagaranandsuri, Acharya Rajshekharasuri) and commentators. Specific points raised include:

- The description of the twelve heavens in a particular sutra (Shashthipad-padvitpa) aligns with Shvetambara views.

- The mention of 'hunger' and 'thirst' as afflictions (parishaha) for Kevali Bhagwants in another sutra (Shi-nin-e) supports the Shvetambara belief in Kevali-bhukti (eating by Kevalis).

- Certain sutras (Nava Dharmadharmaputa, Trishayee) contradict Digambara beliefs.

- The author's own work, "Prashamrati," depicts the monastic attire, which is argued to be consistent with Shvetambara practices.

- The colophon at the end of his commentary ("Swopajna Bhashya") mentions him as belonging to the "Uchchhanagar" branch, whose lineage is traced in Shvetambara scriptures.

- Arguments for Digambara affiliation are also acknowledged, citing scholars like Pandit Phoolchand Shastri and Pandit Kailashchandra.

- Some scholars propose the author belonged to the "Papaniya" sect.

- The commentator, Dhirajlal Mehta, leans towards the Shvetambara affiliation based on the presented evidence.

-

Author's Biographical Details (from Swopajna Bhashya Prasasti):

- His spiritual lineage traces back through Shivashri (great-grandfather), Ghoshnandi (grandfather, knowledgeable in 11 Angas), Mundapad Shraman (great-grandfather), and Mool (grandfather) – all referred to with high honorifics.

- Born in a town called "Nyagrodhika."

- Resided and authored the work in the city of Kusumpur (Pataliputra, modern Patna).

- Belonged to the Kausbini gotra.

- His father's name was Swati.

- His mother's name was Vatsi.

- He belonged to the Uchchhanagar branch.

- The purpose of writing the sutra was to alleviate the suffering of a world whose intellect was corrupted by false philosophies.

-

Author's Time Period:

- The exact time of Umaswati is difficult to ascertain definitively due to a lack of conclusive evidence.

- Scholarly opinions vary between the Shvetambara and Digambara traditions.

- Based on his association with the Uchchhanagar branch, which originated four generations after Aryasuhasti (who passed away 291 years after Mahavir's nirvana), it's estimated he lived around 500 years after Mahavir's nirvana, placing him in the 1st or 2nd century CE.

- The Digambara commentary "Sarvarthasiddhi" by Pujyapad Swami is dated to the 5th-6th century CE, suggesting Umaswati lived before this period.

-

Literature on Tattvarthadhigama Sutra:

- Numerous commentaries (Tikas) and critical analyses (Vivechan) have been written on this sutra by esteemed scholars from both traditions.

- Umaswati himself wrote a commentary called "Swopajna Bhashya."

- A list of prominent Shvetambara Tikas is provided, including those by Siddhasen Gani, Haribhadrasuri, Yashobhadrasuri, Yashovijayji, and Malayagiri.

- A list of prominent Digambara Tikas is also given, including Sarvarthasiddhi by Pujyapad Swami, Tattvarthavarttikalankara by Akalankacharya, and Shlokavartika by Acharya Vidyananda.

- The commentary notes the availability of critiques in Gujarati, Hindi, and English.

-

Purpose of the Present Gujarati Commentary:

- To serve as a concise textbook for students and scholars.

- To provide a brief but clear understanding of the sutras' meanings.

- To facilitate the study and teaching of the Tattvarthadhigama Sutra, which has seen increased interest globally.

- The methodology includes presenting the sutras in Sanskrit type, Gujarati type, and then with word-by-word separation in Gujarati for easier pronunciation and understanding.

-

Acknowledgments:

- The commentator expresses gratitude to Param Pujya Acharya Bhagwant Shrimad Vijay Hemchandrasurishwarji M.S. for inspiration, the Jinshasan Aradhana Trust for publishing support, and Pujya Sadhvi Shashi Prabhashriji M.S. for encouraging the printing of 500 copies.

- The commentator humbly seeks forgiveness for any unintentional errors arising from their limited knowledge.

This summary aims to capture the essence of the introductory material and the overall intent of the commentary, highlighting the text's importance, the author's background, and the contextualization of the commentary within the broader Jain scholarly tradition.