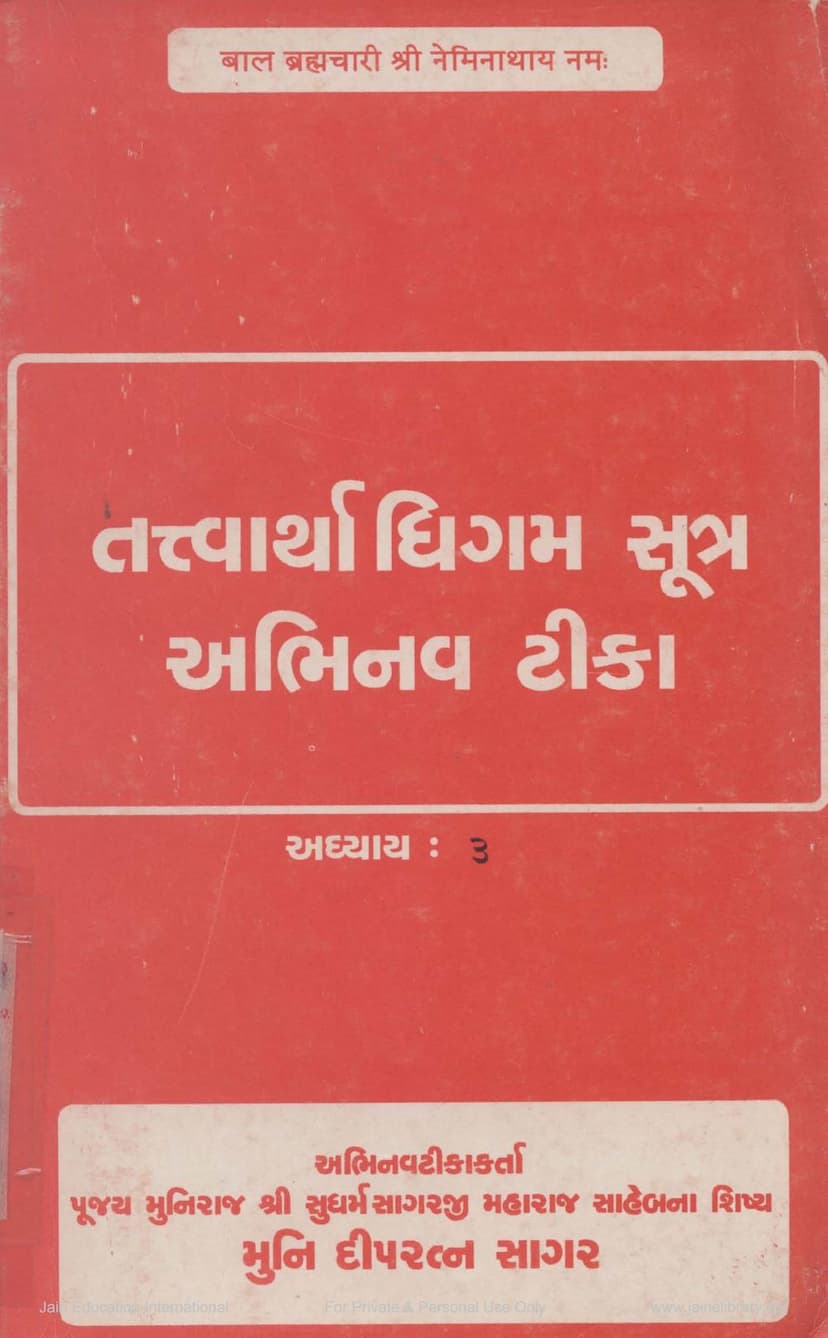

Tattvarthadhigam Sutra Abhinav Tika Adhyaya 03

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the provided Jain text, "Tattvarthadhigam Sutra Abhinav Tika Adhyaya 03," in English:

Book Title: Tattvarthadhigam Sutra Abhinav Tika Adhyaya 03 Author(s): Dipratnasagar, Deepratnasagar (commentary by Muni Deepratnasagar, disciple of Pujya Muniraj Shri Sudharmasagarji Maharaj Saheb) Publisher: Shrutnidhi Ahmedabad / Abhinav Shrut Prakashan Catalog Link: https://jainqq.org/explore/005033/1

Overview of Chapter 3:

Chapter 3 of the Abhinav Tika (commentary) on the Tattvarthadhigam Sutra focuses primarily on the realms of hell (Narak) and the middle world (Madhya Lok). It comprises a total of 18 sutras, which, despite their relatively small number, contain a vast amount of information. The chapter's core aim is not just to present information about these realms but to instill a sense of detachment and guide the soul towards liberation (Moksha) by understanding the nature of the cycle of birth and death (Samsara) within the four life-forms (Chatur-gati). Studying the forms of hell, lower beings (Tiryanch), and humans provides a foundation for the "Lok Swarup Bhavna" (contemplation on the nature of the universe) and "Samsthan Vichay Dhyan" (meditation on the forms of the universe), ultimately leading to detachment and liberation.

Summary of Key Sutras and Concepts:

-

Sutra 1: Description of the Seven Underworlds (Narakas)

- The sutra identifies the seven hellish realms, named from lowest to highest: Ratnaprabha, Sharkaraprabha, Valukaprabha, Pankaprabha, Dhumaprabha, Tamaprabha, and Mahatamaprabha.

- These realms are situated one below the other, becoming progressively wider as they descend.

- The sutra explains their foundational structure, indicating they are supported by dense water (Ghanodadhi), dense air (Ghanvaata), subtle air (Tanuvata), and space (Aakash).

- The commentary elaborates on the meaning of "Prabha" (radiance) associated with each layer, highlighting the characteristics of each realm (e.g., Ratnaprabha is characterized by the radiance of jewels).

- It also discusses the two classifications of hellish earth names: Nir anvaya (without etymological meaning) and Sanvaya (with etymological meaning), providing alternative names found in some scriptures.

- The profound philosophical significance of the "Prabha" suffix is explained, signifying the inherent nature or essence of each hellish plane.

-

Sutra 2: The Presence of Narakas within Each of the Seven Underworlds

- This sutra states that Narakas (inhabitants of hell) reside within each of the seven hellish planes described in the previous sutra.

- The commentary details the placement and structure of these Narakavasas (dwellings of hell-dwellers), explaining that they occupy the central portions of each hellish plane, with portions above and below being left unoccupied.

- It elaborates on the concept of "Pratara" (levels or storeys) within each hellish plane, noting their varying number (13 in Ratnaprabha down to 1 in Mahatamaprabha) and their height (3000 yojan).

- The immense distances between these Pratara are also calculated.

- The commentary provides the total number of Narakavasas across all seven hells (84 lakh) and names the central Narakavasas.

-

Sutra 3: The Ever-Increasing Wretchedness of the Lower Realms

- This sutra describes the progressively more unfortunate and intense nature of the hellish realms as one descends.

- It highlights that each lower realm is characterized by increasing unpleasantness in terms of life-force (Leshyā), mental states (Parinam), physical bodies (Deh), feelings of suffering (Vedana), and modifications of the subtle body (Vikriya).

- The commentary details the specific types of Leshyā (Kṛṣṇa, Nīla, Kāpota), the intensity of suffering, and the nature of the hellish beings' bodies and experiences, emphasizing the worsening conditions in lower hells.

-

Sutra 4: The Mutual Torment Inflicted by Hell-Dwellers

- This sutra describes the suffering caused by the hell-dwellers to each other.

- The commentary explains that hell-dwellers, driven by intense enmity and deluded by their false knowledge (Vibhanga Gyan), inflict great suffering upon one another using various weapons created through their willpower (Vaikriya Samuddhata).

- It differentiates between the suffering caused by the environment (Kshetra Kruta), by each other (Paraspar Udit), and by higher powers (Paramadhāmī Kruta), with this sutra focusing on the second type.

-

Sutra 5: The Torment Inflicted by the Asuras (Paramadhamis)

- This sutra details the suffering caused by Asuras (demonic beings, often referred to as Paramadhamis) to the hell-dwellers.

- Crucially, it specifies that this torment is primarily experienced in the first three hellish planes (Ratnaprabha, Sharkaraprabha, and Valukaprabha) as the Asuras' influence is limited to these realms.

- The commentary lists fifteen types of Asuras (e.g., Amba, Ambarisha, Shyama) and describes in graphic detail the horrific torments they inflict, such as boiling in oil, being torn apart, and being forced to consume foul substances. The purpose of this detailed, albeit disturbing, description is to instill extreme aversion to hellish existence.

-

Sutra 6: The Lifespans of Hell-Dwellers

- This sutra specifies the maximum lifespan of the beings in each of the seven hellish planes.

- The lifespans are given in Sagaropama (a vast unit of time), increasing from one Sagaropama in the first hell to thirty-three Sagaropama in the seventh hell.

- The commentary provides a table of these lifespans and also discusses the concept of "Palyopama" and "Sagaropama" as units of time, explaining their immense scale. It also touches upon the minimum lifespans (Antarmuhurta) which will be discussed later.

-

Sutra 7: Description of the Islands (Dwipa) and Oceans (Samudra)

- This sutra marks the beginning of the description of the Middle World (Madhya Lok), also known as Tiryak Lok.

- It introduces the concept of continents (Dwipa) and oceans (Samudra), starting with Jambudvipa and the Lavana ocean, which are described as having auspicious names.

- The commentary explains the cosmological structure of the universe, including the concept of Rajuloka (a measure of the universe's extent), and the three divisions of the world: Adholok (lower world), Madhya Lok (middle world), and Urdhvalok (upper world).

- It details the concentric arrangement of Dwipas and Samudras, with each subsequent island and ocean being twice the size of the preceding one, and all being circular (Valayakar).

-

Sutra 8: The Circular Arrangement and Doubling of Islands and Oceans

- This sutra elaborates on the structure of the Dwipas and Samudras, emphasizing their circular shape and the progressive doubling of their width.

- It states that each island is encircled by an ocean, and each ocean is encircled by another island, forming a series of concentric rings.

- The commentary provides specific measurements and descriptions of various Dwipas and Samudras, starting from Jambudvipa and Lavana Samudra, and extending to Swyambhuramana Samudra. It also delves into the complex system of counting "Asankhyata" (innumerable) and "Ananta" (infinite) as units of measure.

-

Sutra 9: Jambudvipa and Mount Meru

- This sutra introduces Jambudvipa as the central and innermost continent, with a width of one lakh yojan.

- It highlights the presence of Mount Meru at the very center of Jambudvipa, describing it as the "navel" of the continent.

- The commentary provides detailed descriptions of Mount Meru's dimensions, its structure (divided into three parts: lower, middle, and upper), the four celestial groves (Vanas) around its base (Bhadralshala, Nandana, Saumanasa, Panduka), and the four significant rock platforms (Shilas) where the birth-annointments of Tirthankaras take place.

-

Sutra 10: The Seven Regions (Kshetra) of Jambudvipa

- This sutra names the seven major regions within Jambudvipa: Bharat, Hemvant, Harivarsha, Mahavideha, Ramya, Hairanyavat, and Airavat.

- The commentary explains the geographical arrangement of these regions, separated by mountain ranges (Varshadhara Parvat), and highlights their symmetrical characteristics. It also discusses the nomenclature of these regions, often relating to the presiding deities or dominant features.

-

Sutra 11: The Mountains Separating the Regions

- This sutra names the six great mountain ranges (Varshadhara Parvat) that divide Jambudvipa into its seven regions. These are Himavan, Mahahimavan, Nishadha, Nilavan, Rukmi, and Shikari.

- The commentary provides detailed descriptions of these mountains, including their dimensions, composition (e.g., made of gold, silver, jewels), the regions they border, the rivers originating from them, and the celestial abodes (Jinalayas) located on them. It also explains the meaning behind the names of the regions and mountains.

-

Sutra 12: The Continents and Oceans of Dhātakīkhaṇḍa

- This sutra states that the continents and oceans in Dhātakīkhaṇḍa are twice the size of their counterparts in Jambudvipa and are also arranged circularly.

- The commentary reiterates the concept of concentricity and doubling, applying it to the structure of Dhātakīkhaṇḍa, which is divided into two halves by the Ikṣukāra mountains. It details the number of regions and mountains within each half and mentions the presence of two Mount Merus.

-

Sutra 13: The Continents and Oceans of Puṣkaravara

- This sutra describes the half of Puṣkaravara island, stating that its regions and mountains are also twice the size of those in Dhātakīkhaṇḍa.

- The commentary explains that Puṣkaravara is divided into two halves by the Mānuṣottara mountain. It then details the regions, mountains, and the two Mount Merus located within the eastern and western halves of Puṣkaravara, emphasizing the doubling of dimensions compared to Dhātakīkhaṇḍa.

-

Sutra 14: The Location of Humans

- This sutra clarifies that humans (Manushya) reside within the regions and sub-regions (like Antardvipas) that lie before the Mānuṣottara mountain.

- The commentary explains the concept of Aryas (civilized people) and Mlecchas (uncivilized people) based on their location (within the 25.5 Arya-deshas in Bharat and other regions), their adherence to Dharma, and their refined conduct. It provides detailed lists of these regions and the characteristics of Aryas and Mlecchas. It also clarifies that beings in the Bhoga Bhumis (like Devakuru and Uttarakuru) are considered Mlecchas because they lack the opportunity for strenuous spiritual practice.

-

Sutra 15: Types of Humans (Arya and Mleccha)

- This sutra categorizes humans into two main types: Aryas and Mlecchas.

- The commentary elaborates on the definition of Arya, which is based on factors like birth in Karma Bhumi, lineage, actions, skills, language, and adherence to righteous conduct. It lists the 25.5 Arya-deshas within Bharat and Airavat, the regions within Mahavideha, and the characteristics of beings in Bhoga Bhumis (considered Mlecchas due to the absence of spiritual struggle).

-

Sutra 16: The Karma Bhumis

- This sutra identifies the Karma Bhumis (lands of action), which are those regions where the possibility of spiritual liberation exists.

- It clarifies that the regions of Devakuru and Uttarakuru are excluded from this classification, despite being located within Mahavideha, because they are Bhoga Bhumis (lands of enjoyment) where the opportunity for strenuous spiritual practice is absent. The primary criteria for a Karma Bhumi are the presence of Tirthankaras, the possibility of liberation through self-effort, and the practice of meritorious actions.

-

Sutra 17: Lifespans of Humans

- This sutra states the maximum lifespan of humans as three Palyopama and the minimum lifespan as Antarmuhurta.

- The commentary provides a detailed explanation of Palyopama and Antarmuhurta as units of time, including their calculation through various analogies (like counting mustard seeds filling a well). It also discusses the lifespans of humans in different Yugas (Avasarpini and Utsarpini) and in various regions.

-

Sutra 18: Lifespans of Tiryanchs (Sub-Human Beings)

- This sutra indicates that the lifespans of Tiryanchs (beings in the animal and lower forms) are also measured in Palyopama and Antarmuhurta, mirroring human lifespans.

- The commentary elaborates on the diverse lifespans of various Tiryanch species (from one-sensed beings to five-sensed animals) and discusses the concepts of Bhavasthiti (lifespan within a specific existence) and Kayasthiti (the potential for repeated births within the same life-form). It highlights that while lifespans can vary greatly, the ultimate goal of attaining liberation is only possible in the human birth.

Commentary's Approach (Abhinav Tika):

The "Abhinav Tika" by Muni Deepratnasagar offers a modern and accessible commentary. It breaks down complex concepts, provides etymological explanations for names, and connects the descriptions to the broader Jain philosophical framework, particularly the path to Moksha. The commentary aims to make the profound teachings of the Tattvarthasutra understandable for contemporary readers.

This summary provides a foundational understanding of the key themes and concepts covered in Chapter 3 of this specific commentary.