Tattvartha Sutra

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

The provided text is the first chapter of the Tattvartha Sutra by Acharya Umaswati, along with introductory materials and a table of contents for the entire work. Here's a comprehensive summary based on the provided pages:

About the Text:

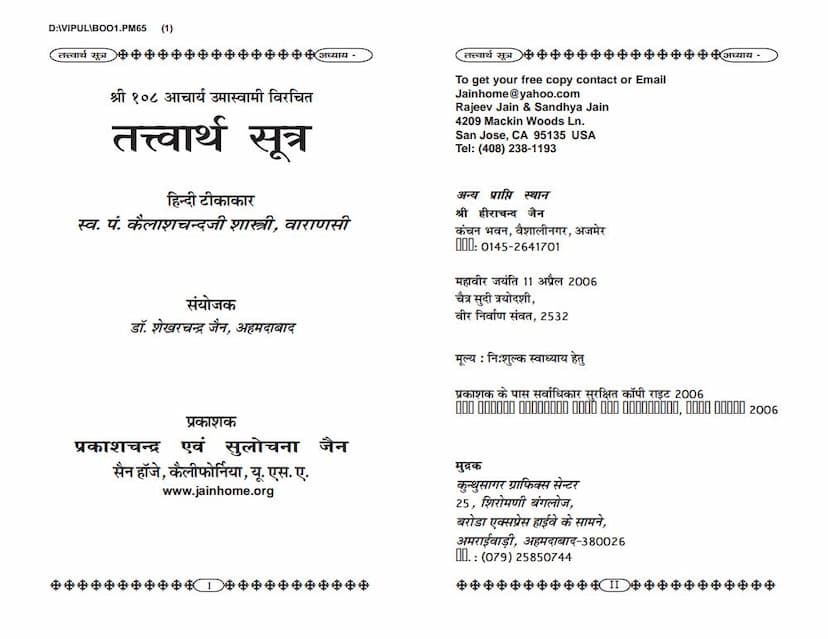

- Title: Tattvartha Sutra (तत्वार्थ सूत्र)

- Author: Acharya Umaswati (also referred to as Umaswami)

- Publisher: Prakashchandra evam Sulochana Jain, USA

- Commentary (Hindi): Late Pandit Kailashchandraji Shastri, Varanasi

- Significance: The Tattvartha Sutra is a highly revered and foundational text in Jainism, considered the first Jain scripture composed in Sanskrit. It holds a prominent place in the Digambara Jain tradition and has been elaborated upon by prominent Acharyas like Pujyapad Swami, Akalank Swami, and Vidyanand Swami, with commentaries such as Sarvarthasiddhi, Rajavartika, and Shlokavartika. Pandit Kailashchandraji Shastri's Hindi commentary is noted for its spiritual perspective, simplicity, and clarity, making the profound principles of Jainism accessible.

Core Jain Philosophy Presented in the Introduction and First Chapter:

The introductory pages and the first chapter of the Tattvartha Sutra lay out the fundamental purpose and principles of Jainism.

-

Purpose of Jainism: The ultimate goal of Jainism is to liberate all suffering beings from the cycle of birth and death (Samsara) across various states of existence (Nigoda, Naraka, Tiryancha, Deva, and Manushya) and to establish them in eternal, blissful, and indivisible spiritual happiness – Moksha (liberation).

-

Role of Tirthankaras: Tirthankaras, born under auspicious astrological alignments, are spiritually advanced souls who, despite possessing immense worldly power and enjoyments, renounce them. Through intense penance, they destroy all karmas that obscure their true nature, becoming omniscient and passionless Kevalis. Their teachings form the authentic path to liberation.

-

The Path to Moksha (The Moksha Marga): The very first sutra of the Tattvartha Sutra, "Sammyagdarshana-jnana-charitrani mokshamargah" (सम्यग्दर्शनज्ञानचारित्राणि मोक्षमार्गः), defines the path to liberation as the combined practice of Right Faith (Samyagdarshana), Right Knowledge (Samyagjnana), and Right Conduct (Samyakcharitra). These three are not sequential but must be practiced together.

-

Right Faith (Samyagdarshana): Defined as "Tattvartha-shraddhanam samyagdarshanam" (तत्त्वार्थश्रद्धानं सम्यग्दर्शनम्), Right Faith is the unwavering conviction in the true nature of reality (Tattvas). It is described as having two aspects:

- Saraga Samyagdarshana (with attachment): Characterized by feelings of introspection (Prashama), fear of worldly existence (Samvega), compassion for all beings (Anukampa), and acceptance of the Jina's teachings (Astikya).

- Vitaraga Samyagdarshana (without attachment): This is the highest state of purification.

-

Origin of Right Faith: Right Faith arises either spontaneously (Naisargika or Nisargaja) or through the teachings of others (Adhigamaja). The underlying cause for both is the subsidence, destruction, or partial destruction of the deluding karma (Darshana Mohaniya Karma).

-

The Seven Tattvas (Realities): The scripture then enumerates the seven fundamental realities of Jain philosophy:

- Jiva (Soul): Possesses consciousness (Chetana).

- Ajiva (Non-soul): Lacks consciousness. This category includes Pudgala (matter), Dharma (principle of motion), Adharma (principle of rest), Akasha (space), and Kala (time).

- Asrava (Inflow of Karma): The channels through which karmic particles enter the soul.

- Bandha (Bondage of Karma): The actual bondage of karmic particles to the soul.

- Samvara (Stoppage of Karma Inflow): The cessation of new karmic influx.

- Nirjara (Shedding of Karma): The exhaustion and shedding of accumulated karma.

- Moksha (Liberation): The complete liberation from all karmas and the cycle of rebirth.

-

The Seven Tattvas as the Subject Matter: The text explains that the seven Tattvas are the principal subjects of this scripture because they encompass the entire cycle of existence and liberation.

-

Nigshepas (Categories of Understanding): To understand any subject accurately, including the Tattvas, four categories are introduced:

- Nigama (Name): Naming something without its inherent qualities (e.g., naming a child 'Indra' without him possessing Indra's qualities).

- Nishchaya (Establishment): Representation of something through an image or symbol (e.g., establishing an image of a Tirthankara).

- Dravya (Substance): Referring to the potential or undeveloped state of something (e.g., calling a block of wood destined to become an idol, 'Indra').

- Bhava (Actual State): Referring to the Tattva in its actual, fully manifested form (e.g., calling the actual Indra, 'Indra').

-

Pramana and Naya (Means of Knowledge): The true knowledge of the Tattvas is gained through Pramana (valid, comprehensive knowledge) and Naya (partial or specific perspective).

- Pramana: Aims to know the entire object (e.g., the five types of knowledge: Mati, Shruta, Avadhi, Manahparyaya, Kevala).

- Naya: Focuses on a particular aspect or perspective of an object (e.g., seven Nayas: Naigama, Sangraha, Vyavahara, Rju-sutra, Shabda, Samabhirudha, Evam-bhuta).

-

Other Methods of Understanding: Besides Pramana and Nayas, understanding is also achieved through six "Anuyogas" (ways of analysis): Nidesha (description), Swamitva (ownership), Sadhana (cause), Adhikara (place), Sthiti (duration), and Vidhana (classification). An additional eight Anuyogas are also mentioned: Sat (existence), Sankhya (number), Kshetra (area), Sparshana (contact), Kala (time), Antara (interval), Bhava (state), and Alpabahutva (relative quantity).

-

Types of Knowledge (Jnana): The chapter details the five types of valid knowledge:

- Matijnana (Sensory/Mental Knowledge): Acquired through the senses and mind.

- Shrutajnana (Scriptural/Inferred Knowledge): Derived from Matijnana or from teachings.

- Avadhijnana (Clairvoyance): Direct knowledge of subtle, distant, or hidden material objects.

- Manahparyayajnana (Telepathy): Direct knowledge of the thoughts of others.

- Kevalajnana (Omniscience): Absolute and complete knowledge of all realities.

-

Pramana (Valid Means): The text clarifies that only these five types of knowledge are valid means of knowledge (Pramana), not the sensory organs or their contact with objects.

-

Pramana Classification: Knowledge is classified into two categories:

- Paroksha (Indirect): Matijnana and Shrutajnana, which depend on external aids (senses, mind, teachings).

- Pratyaksha (Direct): Avadhijnana, Manahparyayajnana, and Kevalajnana, which arise from the soul's own capacity.

-

Subtleties of Knowledge: The chapter further elaborates on the subtypes and characteristics of Matijnana (e.g., Avagraha, Eha, Avaya, Dharana) and Shruta Jñana, and the scope of Avadhi and Manahparyaya Jñana.

Overall Purpose of the First Chapter:

The first chapter serves as an introduction to the entire system of Jain philosophy, defining the ultimate goal (Moksha), the path to achieve it (Right Faith, Knowledge, Conduct), the fundamental realities (Seven Tattvas), and the methods of understanding these realities (Pramana, Naya, Nigshepas, Anuyogas, and types of Knowledge). It sets the stage for the detailed exposition of each Tattva in the subsequent chapters.