Tattvartha Sutra

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

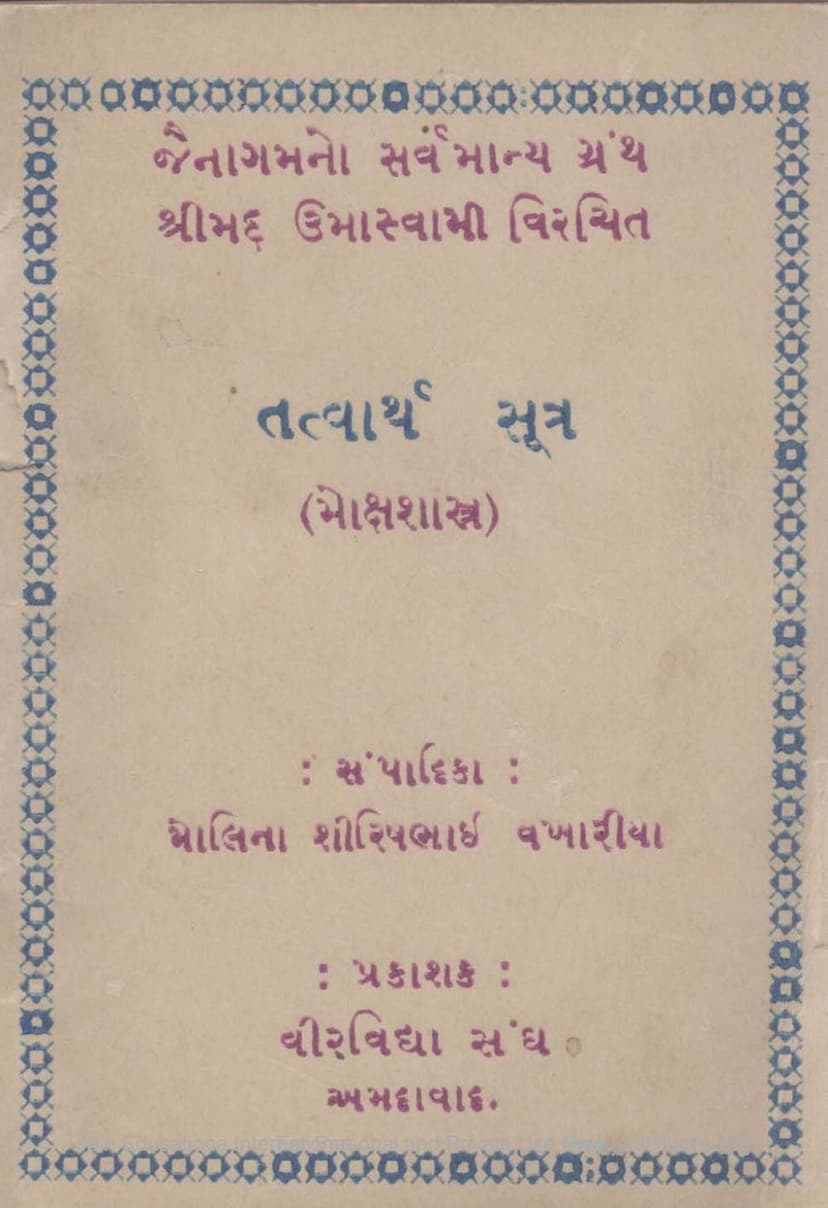

This document is a Gujarati translation and commentary of the Tattvartha Sutra, a fundamental Jain text authored by Acharya Umaswami. It is presented as "Mokshashastra" (The Scripture of Liberation).

Here's a breakdown of the content based on the provided text:

Book Details:

- Title: Tattvartha Sutra (also referred to as Mokshashastra)

- Author: Acharya Umaswami

- Editor/Compiler: Malina Shirishbhai Vakhariya

- Publisher: Veervidya Sangh, Ahmedabad

- First Edition: January 28, 1991

- Purpose: Intended for private and personal study and for distribution to the Jain community.

- Catalog Link: https://jainqq.org/explore/005342/1

Introduction (Prastavana):

- The Tattvartha Sutra is an ancient and highly revered text in Jainism, considered a foundational scripture.

- It is praised for its concise yet comprehensive presentation of Jain philosophy in Sanskrit sutras.

- Its significance is such that it is universally accepted across all Jain sects (Digambar, Shvetambar, Sthanakvasi).

- It is likened to the Quran for Muslims, the Bible for Christians, and the Gita for Brahmins in its importance.

Structure and Content Overview:

The text is divided into ten chapters (Adhyayas), each focusing on specific aspects of Jain philosophy:

-

Chapter 1 (Pratham Adhyay):

- Defines the path to liberation (Moksha Marga) as the union of Right Faith (Samyak Darshan), Right Knowledge (Samyak Jnana), and Right Conduct (Samyak Charitra).

- Explains the nature of Right Faith (faith in the true nature of reality/principles).

- Details the Seven Tattvas (principles): Jiva (soul), Ajiva (non-soul), Asrava (influx of karma), Bandha (bondage of karma), Samvara (cessation of karma influx), Nirjara (shedding of karma), and Moksha (liberation).

- Discusses methods of knowing these principles: Niskhepa (Name, Establishment, Substance, Form), Pramananaya (validity and partial views), and various analytical categories (Nirdesh, Swamitva, Sadhana, Adhikaran, Sthiti, Vidhan, Sat, Sankhya, Kshetra, Sparshan, Kalan, Antar, Bhav, Alpamahattva).

- Elaborates on the five types of knowledge (Jnana): Mati (sense-based), Shruta (scriptural), Avadhi (clairvoyance), Manahparyaya (telepathy), and Kevala (omniscience).

- Differentiates between paroksha (indirect) and pratyaksha (direct) knowledge.

- Explains the various classifications and subsets of Mati Jnana and Shruta Jnana.

-

Chapter 2 (Dwitiya Adhyay):

- Focuses on the soul (Jiva) and its unique states (Asadharana Bhavas) – Oupashamik, Kshayik, Mishra/Kshayopashamik, Audayik, and Parinamik.

- Details the different types and classifications within these states.

- Defines the soul by its characteristic of "Upayoga" (consciousness or application of soul's nature).

- Explains the classification of souls into Samsari (those in the cycle of birth and death) and Mukta (liberated).

- Further categorizes Samsari souls as Manasaka/Sanjni (with mind) and Amanaska/Asanjni (without mind).

- Discusses souls based on their senses (Indriyas) and the types of souls: Ekendriya (one-sensed), Trindriya (three-sensed), Chaturindriya (four-sensed), and Panchendriya (five-sensed), as well as the classification of Ekendriya into Sthavara (immobile) and the five types of earth-bodied, water-bodied, fire-bodied, air-bodied, and plant-bodied souls.

- Describes the five types of bodies (Sharira): Audarik, Vaikriyik, Aharak, Taijas, and Karman.

- Explains the concept of transmigration and the process of entering a new body.

-

Chapter 3 (Tritiya Adhyay):

- Focuses on the lower worlds (Adholok), describing the seven hellish realms (Naraka prabha).

- Details the number of dwelling places (Bil) in each hell.

- Describes the suffering, classifications of beings (Narakis), and the nature of their existence, including their severe suffering and the causes of their rebirth in hell.

- Explains the lifespan of Narakis.

- Discusses the middle world (Madhyalok), detailing the Jambu Island and the progression of island-continents (Dvipa-Samudras).

- Describes the structure and arrangement of these Dvipas and Samudras.

- Focuses on Jambu Island, the central Meru Mountain, and the seven regions (Varsha) within it.

- Explains the mountain ranges separating these regions and their characteristics.

- Details the lakes and lotuses on these mountains and the celestial beings residing there.

- Describes the rivers flowing through the regions and their tributaries.

- Explains the size and progression of regions and mountains.

- Discusses the cyclical nature of time (Utsarpini and Avasarpini) and its impact on life forms in the Bharat and Airavat regions, contrasting it with the unchanging nature of other regions.

- Describes the lifespan and bodily characteristics of beings in various regions.

-

Chapter 4 (Chaturtha Adhyay):

- Focuses on the celestial realms (Urdhva Lok), detailing the four types of celestial beings (Deva): Bhavanvasi (dwellers of lower celestial mansions), Vyantar (intermediate celestial beings), Jyotishi (luminous celestial beings), and Vaimanika (celestial beings residing in aerial vehicles).

- Explains the classifications within these types and their respective lifespans, powers, and enjoyments.

- Details the various celestial classes like Indras, Samanikas, Trayastrimshas, etc.

- Discusses the different forms of celestial reproduction and the evolution of their experiences, from physical interaction to purely mental union.

- Explains the types of celestial vehicles (Viman) and their hierarchical arrangement.

- Describes the respective lifespans, from the lower Bhavanvasis to the highest Vaimanikas.

- Mentions the different Lésyas (color of the soul's aura) of celestial beings.

-

Chapter 5 (Panchama Adhyay):

- Focuses on the non-soul (Ajiva) element.

- Defines the five types of Ajiva: Dharma (medium of motion), Adharma (medium of rest), Akash (space), Pudgala (matter), and Kala (time). (Note: The text clarifies Kala as a substance, making it six substances in total: Jiva and Ajiva, with Ajiva comprising the other five).

- Explains the fundamental characteristics of substances: eternity, immutability in essence, and the possession of qualities and modifications.

- Details the nature of Pudgala (matter) and its properties (touch, taste, smell, color).

- Explains the infinite nature of space and the immense, though not infinite, number of regions in time, Dharma, and Adharma.

- Discusses the concept of regions (Pradesha) within substances.

- Explains the function of Dharma (enabling movement), Adharma (enabling rest), and Akash (providing space for all substances).

- Describes the functions of Pudgala (forming bodies, speech, mind, breath) and Kala (enabling change and duration).

- Discusses the physical manifestations of Pudgala, such as sound, bondage, color, and form.

- Explains the atomic (Anu) and composite (Skandha) nature of matter.

-

Chapter 6 (Shashtha Adhyay):

- Focuses on the influx of karma (Asrava) and the causes of karma.

- Defines Asrava as the movement of soul-matter that leads to karma bondage.

- Classifies Asrava into auspicious (Puṇya) and inauspicious (Papa) based on the actions of mind, speech, and body (Yoga).

- Explains the concept of Sayog and Ayog Asrava (karma influx with or without the involvement of mind, speech, or body).

- Details the causes for the influx of specific karmas, such as knowledge-obscuring karma, perception-obscuring karma, feeling-producing karma, deluding karma, lifespan-determining karma, name-karma, status-determining karma, and obstruction-causing karma.

- Explains the specific actions and attitudes that lead to the accumulation of these different types of karma.

-

Chapter 7 (Saptama Adhyay):

- Focuses on vows (Vrata) and their practice.

- Defines vows as abstaining from violence, falsehood, stealing, unchastity, and accumulation.

- Categorizes vows into partial (Anu Vrata) and full (Mahavrata).

- Details the supporting practices (Bhāvanā) for each vow to maintain its stability.

- Explains the principles of Ahimsa (non-violence), Satya (truthfulness), Asteya (non-stealing), Brahmacharya (celibacy), and Aparigraha (non-possession).

- Discusses the faults (Atichara) or transgressions of these vows.

- Explains the importance of ethical conduct, virtuous qualities, and renunciation.

- Describes the practice of ethical restraints and the importance of purity of intention.

- Discusses the concept of Salelekhana (voluntary fasting leading to death) as a means of karma purification.

- Explains the nine qualifications for pure Right Faith (Samyak Darshan) and the faults to avoid.

-

Chapter 8 (Ashtama Adhyay):

- Focuses on the bondage of karma (Bandha).

- Reiterates the causes of karma bondage: wrong faith, vows broken, negligence, and passions.

- Explains the four types of karma bondage: Prakriti (nature of karma), Sthiti (duration of karma), Anubhaga (intensity of karma), and Pradesha (quantity of karma).

- Details the numerous sub-types of the eight main karmas (Jnanavarniya, Darshanavarniya, Vedaniya, Mohaniya, Ayushya, Nama, Gotra, Antaraya).

- Explains the duration (Sthiti) and intensity (Anubhaga) of these karmas.

- Defines Pudgala (matter) as the substance that forms karma.

- Distinguishes between meritorious (Puṇya) and demeritorious (Papa) karmas.

-

Chapter 9 (Navama Adhyay):

- Focuses on Samvara (cessation of karma influx) and Nirjara (shedding of karma).

- Defines Samvara as the prevention of new karma entering the soul.

- Explains the means of achieving Samvara: Gupti (control of mind, speech, and body), Samiti (careful conduct in walking, speaking, eating, etc.), Dharma (ten virtues), Anupreksha (contemplation of reality), Parishaha (endurance of hardships), and Charitra (conduct).

- Details the five Samitis and the ten virtues.

- Explains the 22 types of hardships (Parishaha) and their significance for spiritual progress.

- Discusses the five types of Charitra: Samayika, Chedopasthapana, Parihar Vishuddhi, Sukshma Samparaya, and Yathakhyata.

- Explains the practice of Tapas (austerities) as a means of karma shedding (Nirjara).

- Categorizes Tapas into external (Bahya) and internal (Abhyantara).

- Details the six external austerities (Anashana, Avamaudarya, Vrittisamkhyana, Rasatyaga, Vivikta Shayyasana, Kayaklesha).

- Details the six internal austerities (Prayashchitta, Vinaya, Vaiyavritya, Svādhyāya, Vyutsarga, Dhyāna).

- Explains the types of meditation (Dhyana) – Artā, Raudra, Dharma, and Shukla – and their role in spiritual development, with Shukla Dhyana being the path to liberation.

- Discusses the different stages of spiritual development (Gunasthana) and the Parishahas experienced at each stage.

-

Chapter 10 (Dashama Adhyay):

- Focuses on liberation (Moksha).

- Explains the conditions for attaining Kevala Jnana (omniscience) and subsequent Moksha, which involves the destruction of all karmas.

- Defines Moksha as the complete liberation of the soul from karmic bondage, leading to its eternal state of pure consciousness, bliss, and knowledge.

- Clarifies that liberation involves the cessation of not just material karma but also the passions and the states that bind the soul.

- Describes the upward journey of the liberated soul (Siddha) through the universe, its cessation at the end of the Lokakasha (luminous universe), and its eternal existence in a state of infinite bliss and knowledge.

- Provides analogies to explain the soul's upward movement and its eternal dwelling.

- Explains the subtle differences between liberated souls based on various factors like space, time, origin, etc.

This comprehensive summary provides a good overview of the Tattvartha Sutra's teachings as presented in this Gujarati edition.