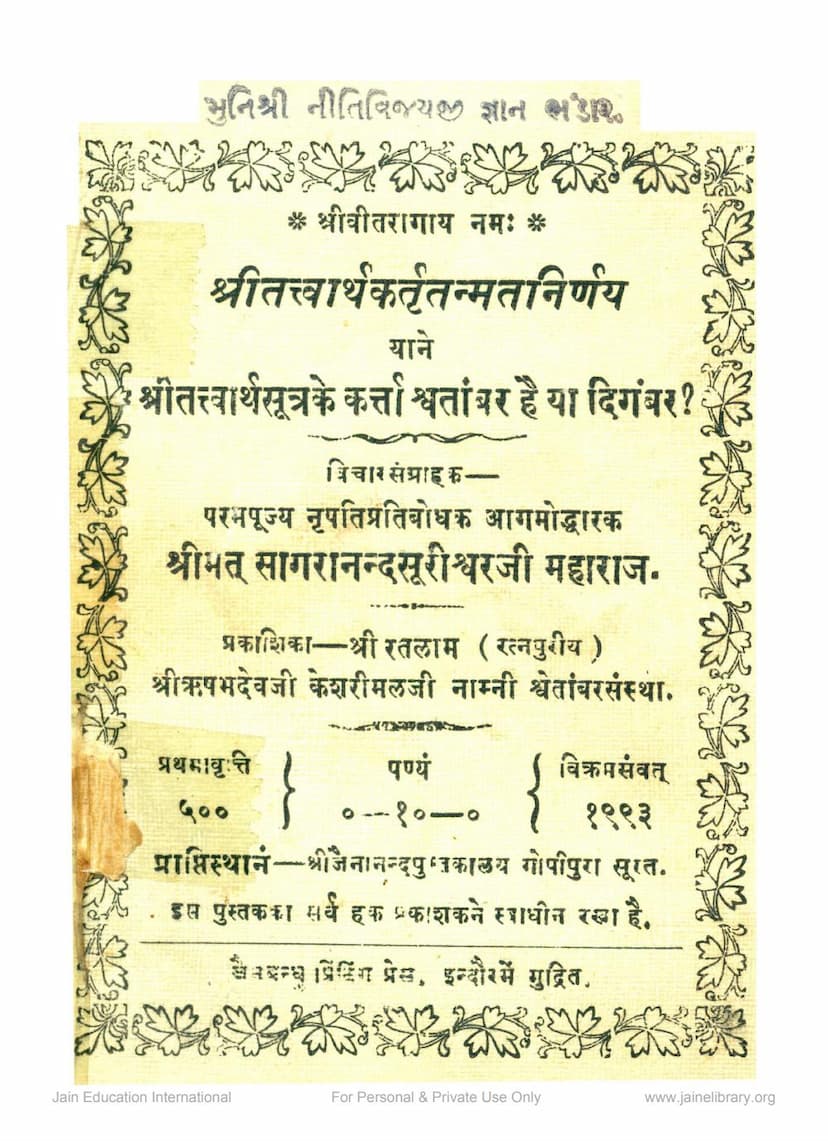

Tattvartha Kartutatnmat Nirnay

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Tattvartha Kartutatnmat Nirnay" by Sagranandsuri, based on the provided pages:

This book, "Tattvartha Kartutatnmat Nirnay," authored by Sagranandsuri and published by the Shri Rishabhdev Kesarimal Jain Shwetambar Sanstha in Ratlam, aims to determine whether the author of the Tattvartha Sutra is a Shwetambar or a Digambar. The author, Sagranandsuri, argues that the Tattvartha Sutra, in its entirety, aligns with Shwetambar philosophy and was authored by a Shwetambar Acharya, Umaswati.

The book systematically presents arguments by analyzing various sutras and philosophical concepts within the Tattvartha Sutra and comparing them with the doctrines of other philosophical schools (इतरदर्शनकार). The core of Sagranandsuri's argument rests on the idea that the Tattvartha Sutra's structure, terminology, and the way it addresses certain concepts demonstrate a clear Shwetambar perspective, often in contrast to or as a clarification of prevailing non-Jain or even Digambar interpretations.

Here's a breakdown of the key arguments presented:

I. Philosophical Underpinnings and Terminology:

- "Moksha-Marga" (Path to Liberation): The use of "Moksha-Marga" is presented as a distinct Jain concept, particularly when contrasted with other religions that used the term "marga" in their own paths.

- "Samagdarsan" (Right Faith): The sutra defining Samagdarsan separately from other aspects of knowledge is seen as a deliberate choice to highlight its unique importance, differentiating it from mere "shraddha" (faith) mentioned in other schools.

- "Nama-Sthapana" (Name and Installation) as Explanatory Tools: The Tattvartha Sutra's use of "Nama-Sthapana" for explanation, in contrast to other schools that relied solely on "Samhita" (collection of texts) for interpretation, is highlighted. This suggests a specific Jain methodological approach.

- "Adhigama" (Acquisition of Knowledge): The term "Adhigama" is used for knowledge, possibly to align with the common usage in other philosophical schools. However, the author clarifies that the emphasis within the Tattvartha Sutra is on "Shuddha Gyan" (Pure Knowledge), and the combination of "Pramana" (means of knowledge) and "Naya" (standpoints) for "Adhigama" reflects a Jain principle of approaching knowledge from multiple perspectives, unlike other schools that might rely solely on "Naya."

- "Dravya-Bhava" (Substance and Attributes/Qualities): The Tattvartha Sutra focuses on "Dravya-Bhava" in describing knowledge, contrasting with other schools that might also include "Kshetra" (space) and "Kala" (time) in their descriptions. This is interpreted as aligning with the Jain view where time and space can be considered as aspects of substance or attributes.

- "Dharana" (Conception/Belief): The author emphasizes the crucial role of "Dharana" in shaping knowledge. Correct "Dharana" is linked to the goal of spiritual upliftment. Knowledge without this correct "Dharana" is considered "Ajnana" (ignorance). This is likened to how a blind person cannot discern what to accept or reject, or how mistaking brass for gold leads to wrong actions.

- "Syadvada" (Doctrine of Conditionality): The Tattvartha Sutra's incorporation of "Syadvada" is a major point. The author argues that other philosophical schools reject "Syadvada," which is why they don't interpret texts comprehensively (upakrama). Jainism's ability to interpret from multiple "Nayas" (standpoints) is seen as a testament to its inclusiveness, whereas other systems limit themselves to single, often contradictory, standpoints.

II. Critiques of Other Philosophical Systems and Their Influence:

The book frequently contrasts Jain principles with those of other philosophical systems, often implying that the Tattvartha Sutra addresses or corrects their limitations:

- Elements as Sentient: While other philosophies consider Earth, Water, Air, and Fire as inert, the Tattvartha Sutra might depict them as sentient, a concept now gaining traction in some modern scientific views.

- Perception and the Mind: Other systems attribute differences in knowledge to sensory organs and their objects. However, Umaswati highlights that even with similar sensory input, the knower's "Dharana" leads to varied knowledge. The concept of an atomic "manas" (mind) in some systems to limit simultaneous knowledge is also discussed, with the argument that if one sense can perceive multiple objects, the knower's "Dharana" becomes paramount.

- Critique of Non-Jain Practices: The sutra's use of harsh words like "unmatta" (mad) for followers of other doctrines in the "Sad-Asat" sutra is seen as a reaction to their "unworthy and false propagation."

- Adoption of External Concepts: The author suggests that the Tattvartha Sutra's structure and some concepts are adopted from other philosophical traditions to make Jainism accessible and to demonstrate its superiority by integrating valid external ideas.

III. Specific Sutras and Their Interpretation:

The text delves into specific sutras to support its claims:

- "Pratyakshamanyat" (Perception is Different): This sutra and others like it are presented as aligning with the principles of other philosophical schools.

- "Matyaadi Jnanani" (Types of Knowledge): The Tattvartha Sutra's focus on "Dravya-Bhava" in describing knowledge is contrasted with other systems that might include "Kshetra" and "Kala."

- "Kritsna Karma Go Moksha" (Liberation is the Cessation of All Karma): This sutra is interpreted as a direct refutation of views that posit liberation as a state of disconnected knowledge or ignorance.

- "Kalashchetyeke" (Time, Some Say): This sutra is used to illustrate the Tattvartha Sutra's engagement with the concept of time and its potential ambiguity, which also serves to highlight the comprehensive nature of the Tattvartha Sutra in relation to "Syadvada."

- The Structure of the Tattvartha Sutra: The ten chapters are seen as reflecting a structure derived from other schools, such as an eight-part structure in some traditions, to explain the path to liberation, with Jainism's ten-chapter structure focusing on the ten types of Shraman Dharma.

IV. The Author of the Tattvartha Sutra:

The book extensively discusses the identity of the author, Umaswati (also referred to as Umaswami by Digambars).

- Praise from Shwetambar Acharyas: The author highlights that Shwetambar Acharyas like Hemchandracharya, Vijaygachchhadhipati, and Malayagiri have praised Umaswati as a foremost "Sangrahakar" (collector/synthesizer) of philosophical truths. This praise is argued to be absent in Digambar scriptures.

- Scholarly Recognition: The fact that later grammarians and scholars from both traditions cite Umaswati further supports his prominence.

- Name Origin: The Shwetambar tradition believes his name comes from his mother Uma and father Swati. The Tattvartha Bhashya itself, according to the book, mentions his father's name as Swati.

- "Vachaka" Title: The Shwetambars believe Umaswati earned the title "Vachaka" (preacher/reciter) after becoming a disciple and mastering the "Drishtivad Ang," the twelfth limb of the Jain Agamas.

- Ancient Origin: The text asserts the antiquity of the Tattvartha Sutra and its author, placing Umaswati before the 10th century CE, citing evidence from later Acharyas.

- "Upakrama" (Thematic Approach): The Shwetambar viewpoint is that Umaswati adopted an "Upakrama" approach to the sutras, explaining them comprehensively, which is only possible for someone who accepts "Syadvada."

V. Critiques of Digambar Interpretations and Variations:

A significant portion of the book is dedicated to comparing Shwetambar and Digambar versions of the Tattvartha Sutra, highlighting perceived differences and arguing that the Digambar versions are often later interpolations or misinterpretations. This includes:

- Number of Sutras: A detailed comparison of the number of sutras in each chapter between the Shwetambar and Digambar traditions is presented, showing discrepancies.

- Specific Sutra Deviations: The author meticulously points out specific sutras that are either omitted, added, or altered in the Digambar tradition. Examples include:

- Omission of "Dwividho Avadhih" (twofold visual knowledge) in the Digambar version.

- Addition of numerous sutras in the third chapter by Digambars, deemed to be too detailed for a "Sangraha" text.

- Alterations in the description of hellish beings, heavens, and their classifications, often in conflict with the Shwetambar count of heavens.

- Differences in the categorization of living beings ( स्थावर and त्रस), with the Tattvartha Sutra's classification of Tejas and Vayu as "Trasa" due to their movement being contrasted with other views.

- Debates on the interpretation of "Syadvada" and the emphasis on "Naya" (standpoints) as a core Jain principle rejected by others.

- Discrepancies in the number of hellish realms and their inhabitants.

- Differences in the enumeration of types of meditation and the qualifications for them.

- Variations in the description of karma, liberation, and the nature of the soul.

- The Role of the Bhashya (Commentary): The book argues that the Bhashya on the Tattvartha Sutra is also authored by Umaswati himself. Numerous examples of the Bhashyakara referring to the sutrakara using phrases like "Uktam Bhavata" (You have said) are presented to demonstrate this shared authorship. The author contends that Digambars reject the Bhashya because it supports Shwetambar interpretations, which would contradict their own doctrines.

VI. Purpose of the Tattvartha Sutra:

The author explains that the Tattvartha Sutra was created to:

- Simplify and Consolidate: To provide a concise and accessible summary of Jain philosophy for those with limited time or interest in extensive scriptures.

- Aid Beginners: To help new students grasp fundamental principles before delving into larger texts.

- Provide a Foundation: To lay a solid understanding of Jain tenets.

Conclusion:

Through detailed textual analysis and comparative philosophy, Sagranandsuri concludes that the Tattvartha Sutra, in its original and intended form, is a foundational text of Shwetambar Jainism, authored by the esteemed Shwetambar Acharya Umaswati. The book aims to clarify these points and encourage all Jain traditions to follow the path laid out by the Vitraag-Praneeta (propounded by the Tirthankaras).