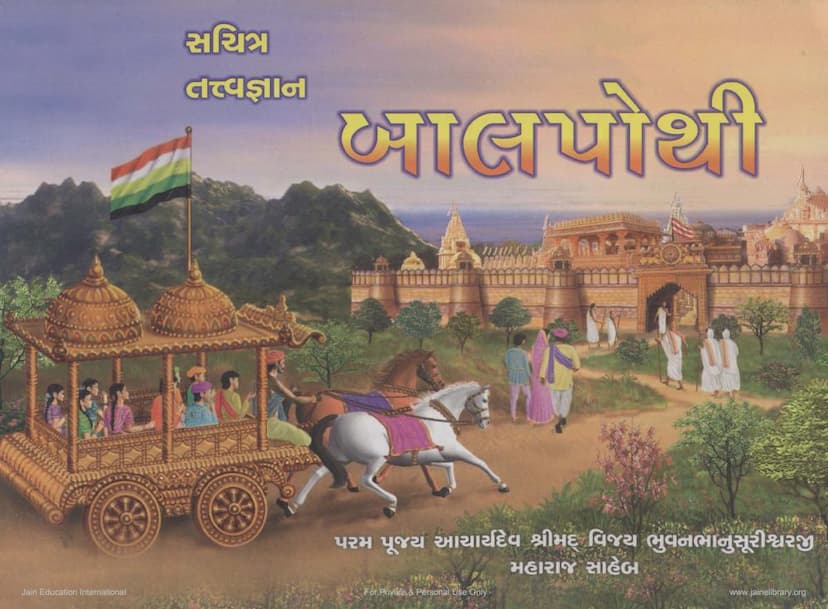

Tattvagyan Balpothi Sachitra

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Tattvagyan Balpothi Sachitra" authored by Bhuvanbhanusuri, published by Divya Darshan Trust, based on the provided pages:

This book, "Tattvagyan Balpothi Sachitra" (Illustrated Book of Tattvas for Children), is a foundational text designed to introduce the core principles of Jainism to young learners in an accessible and engaging manner. Authored by the revered Acharyadev Shrimad Vijay Bhuvanbhanusuri, a prominent figure in the 20th century known for his pioneering use of illustrations in religious education, the book aims to instill moral and spiritual values from a young age.

Key Objectives and Approach:

- Simplify Complex Concepts: The primary goal is to present profound Jain philosophical concepts in simple, child-friendly language, making them easily understandable and relatable to a young audience.

- Illustrative Learning: The book heavily relies on illustrations to depict Jain teachings, recognizing that visual aids are highly effective for children in remembering and grasping information. This approach is presented as a novel and influential method in Jain literature.

- Holistic Development: The book emphasizes that understanding these fundamental Jain principles contributes to the development of individual character, family harmony, social responsibility, and national integrity.

- Bridging the Gap: This re-publication aims to fill a void left since the third edition 32 years prior, making these valuable teachings available once again.

Core Jain Teachings Covered:

The book systematically covers a range of essential Jain concepts, presented in a structured manner:

- Our God, Our Guru, and Parmeshthis: It begins by identifying the supreme beings in Jainism, focusing on the Arihants (the enlightened ones, also known as Tirthankaras or Jineshwaras). These are described as venerable beings who have conquered inner passions (like attachment and aversion), are the founders of the path of liberation, and are worshipped by even celestial beings. The text highlights the 24 Tirthankaras of the current era, and mentions the cyclical nature of Tirthankaras across time. It also introduces the concept of Viharmans Tirthankaras in Mahavideha regions, who are currently propagating the Dharma. The text explains the Arihant's state of Vitragta (passionlessness), their attainment of Kevalgyan (omniscience) through intense penance, and their role in revealing the truth and the path to liberation. The book also emphasizes that becoming a Tirthankara is attainable through dedicated spiritual practice and service.

- Our Guru: The book identifies Sadhus and Munirajs as true Gurus. It details their renunciation of worldly possessions, family, and worldly life, and their adherence to the five great vows (Mahavratas): non-violence, truthfulness, non-stealing, celibacy, and non-possession. Their lives are characterized by strict discipline, adherence to vows, service to others, and continuous spiritual practice through scriptures, penance, and meditation. The three types of Gurus are explained: Acharyas (leaders), Upadhyays (teachers), and Sadhus (practitioners), all of whom strive for liberation.

- Dharma (Religion/Righteousness): Jain Dharma is presented as the path taught by the omniscient, passionless beings. It is categorized into four main types:

- Dan (Charity/Giving): This includes devotional offerings to the Lord, providing food, clothing, and medicine to monks, helping the needy, offering Abhaydan (fearlessness, by not harming living beings), donating to religious causes, and imparting religious knowledge.

- Sheel (Virtue/Conduct): This encompasses celibacy, good conduct, adherence to vows and disciplines, practicing Samayik (equanimity), unwavering faith in the Tirthankaras, Gurus, and Dharma, and showing respect to elders and spiritual guides.

- Tap (Penance/Austerity): This includes practices like fasting (Navkashi, Porisi, Ayambil), reducing intake (Unodari), controlling desires for specific foods (Ras-tyag), enduring hardships for Dharma (Kaykasht), controlling the mind and speech, and scriptural study.

- Bhav (Inner Disposition/Attitude): This involves cultivating pure thoughts and intentions, such as understanding the impermanence of the world, the truthfulness of the Parmeshthis, viewing all beings as friends, abstaining from sin, wishing well for others, and recognizing the soul as distinct from the body. The book emphasizes that Ahimsa (Non-violence), Samyam (Self-control), and Tap (Austerity) are the core principles of Dharma, with Samyakdarshan (Right Faith) being its foundation.

- Daily Routine (Dincharya): A detailed daily schedule is outlined for a Jain householder, emphasizing waking early, prayer, performing religious duties like Pratikraman and Samayik, visiting the temple, listening to discourses from Gurus, eating before sunset, and engaging in scriptural study and virtuous activities.

- Jain Mandir (Temple) - Rituals: The importance of visiting the Jain temple daily is stressed. The book describes the reverence shown upon seeing the temple spire, the practice of Nisithi (renouncing worldly thoughts upon entering), performing Pradakshina (circumambulations), offering prayers and prostrations, and engaging in the ritualistic worship of the deity's idol, which involves cleansing, decorating, and offering various items.

- Seven Deadly Sins and Forbidden Foods (Abhakshya): The text enumerates seven major sins that lead to suffering and rebirth in lower realms: violence, falsehood, stealing, lustful conduct, hunting, theft, and hoarding. It also details forbidden foods (Abhakshya) which are avoided due to the presence of numerous subtle and gross living beings (like meat, alcohol, honey, butter, root vegetables, fungi, stale food, and improperly prepared items). The illustrations vividly depict the negative consequences of consuming these forbidden items and committing sins.

- The Body and the Soul (Jeev): A fundamental distinction is made between the body and the soul. The body is described as inert, made of matter, and incapable of experiencing emotions or knowledge. The soul (Jeev), on the other hand, is the sentient essence that experiences happiness, sorrow, knowledge, and desires. The book uses the analogy of a bird in a cage to explain the soul's entrapment within the physical body. It highlights that the soul is eternal and transmigrates through various life forms based on its Karma.

- Sixteen Stages of the Soul (Jeeva's Six Places): While not fully elaborated in the provided excerpts, this indicates a discussion on the different states or stages of the soul's journey.

- Types of Living Beings: The book classifies living beings into Sthavar (immobile, with one sense organ) and Trasa (mobile, with two to five sense organs).

- Sthavar are further divided into five categories based on their elemental nature: Prithvikaya (earth-bodied), Aakay (water-bodied), Teukaya (fire-bodied), Vayukaya (air-bodied), and Vanaspati-kaya (plant-bodied).

- Trasa are categorized by their number of sense organs: Dvi-indriya (two senses), Tri-indriya (three senses), Chatur-indriya (four senses), and Panch-indriya (five senses), which include beings like animals, humans, and celestial beings (Devas) and hellish beings (Naraki).

- Soul's True and False Nature: The true nature of the soul is described as possessing infinite knowledge, perception, bliss, and power. However, due to the accumulation of Karma, the soul appears clouded and exhibits false characteristics like ignorance, delusion, attachment, aversion, and limitations in perception and knowledge. The eight types of Karma are introduced as the "cloudy veils" that obscure the soul's true essence.

- Soul, Karma, and God (Jeev, Karma, Ishwar): The book asserts that there is no creator God in Jainism. The transmigration and experiences of the soul are governed by Karma, which are subtle material particles that attach to the soul. These karmas are responsible for the creation of bodies and the experiences of happiness and sorrow. The text uses analogies like wind bringing dust or magnets attracting iron to explain how karmas influence the soul without an external divine agent.

- Ajiva and the Six Substances (Ajiva and Shad-dravya): The non-living substances (Ajiva) are explained: Pudgal (matter), Akasha (space), Kala (time), Dharmastikaya (medium of motion), and Adharmastikaya (medium of rest). The Jeev (soul) is the seventh and final substance. Pudgal is the only tangible substance, possessing form, taste, smell, and touch.

- The Universe (Dravya, Paryaya): The universe (Lok) is defined as the abode of the six substances, within the vast expanse of Akasha. The book describes the Jain cosmological model, with its various realms of celestial beings (Devas), human realms, and hellish realms (Naraki), and the central Meru mountain. Dravya (substance) is defined as that which possesses inherent qualities and undergoes changes in states (Paryaya).

- The Nine Tattvas (Navatattva): These are the nine fundamental categories of Jain philosophy that explain the path to liberation:

- Jeev (Soul): The sentient being.

- Ajiva (Non-soul): The inert substances.

- Punya (Merit): Karmas that bring happiness.

- Paap (Demerit): Karmas that bring suffering.

- Asrava (Influx of Karma): The channels through which karmas enter the soul, driven by senses, passions, vows, etc.

- Samvara (Stoppage of Karma): Practices that prevent new karmas from accumulating, like controlling senses and passions.

- Nirjara (Shedding of Karma): Practices that destroy existing karmas, primarily through penance.

- Bandha (Bondage of Karma): The actual attachment of karmic particles to the soul.

- Moksha (Liberation): The state of freedom from all karmas and the cycle of rebirth.

- Punya and Paap (Merit and Demerit): This section elaborates on the consequences of good deeds (Punya) leading to happiness, favorable circumstances, and higher rebirths, while bad deeds (Paap) result in suffering, unfavorable conditions, and lower rebirths. The book provides numerous examples and illustrations to show these outcomes.

- Asrava (Influx of Karma): This explains the root causes of karmic influx, identifying the senses, passions (anger, pride, deceit, greed), lack of vows, and wrong beliefs as the primary drivers.

- Samvara (Stoppage of Karma): The methods to prevent the influx of new karmas are discussed, including the practices of Gupti (control of mind, speech, and body), Samiti (mindful conduct), Parishaha (endurance of hardships), Yati-dharma (conduct of ascetics), Bhavana (contemplation), and Charitra (righteous conduct).

- Nirjara (Shedding of Karma): This section details the practices that help eliminate existing karmas, focusing on the twelve types of austerities (Tap), both external (fasting, reduced intake, etc.) and internal (penance, humility, service, study, meditation).

- Bandha (Bondage of Karma): The book explains how karmas bind the soul, akin to iron or gold chains, and how they have different qualities, durations, intensities, and quantities, influencing the soul's experiences.

- Moksha (Liberation): The ultimate goal of Jainism, Moksha, is described as the state of complete freedom from all karmas and the cycle of birth and death. This leads to an eternal existence of infinite knowledge, perception, bliss, and power. The text emphasizes that achieving Moksha is possible through the consistent practice of Dharma and the eradication of all karmic matter.

Illustrations: The book is richly illustrated, depicting the Tirthankaras, Gurus, various types of living beings, karmic consequences, the universe, and the nine tattvas, making the teachings more vivid and memorable for young readers.

Overall Impact:

"Tattvagyan Balpothi Sachitra" serves as a comprehensive and visually appealing introduction to the core tenets of Jainism. It aims to cultivate a strong foundation of spiritual understanding, ethical conduct, and moral values in children, guiding them towards a virtuous life and the ultimate goal of liberation. The legacy of Acharya Bhuvanbhanusuri's approach through this book is acknowledged for its significant contribution to Jain education.