Sutrakritanga Sutra Part 04

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

This is a comprehensive summary of the provided Jain text, "Sutrakritanga Sutra Part 04" by Manekmuni, based on the pages you've shared:

Overall Context and Purpose:

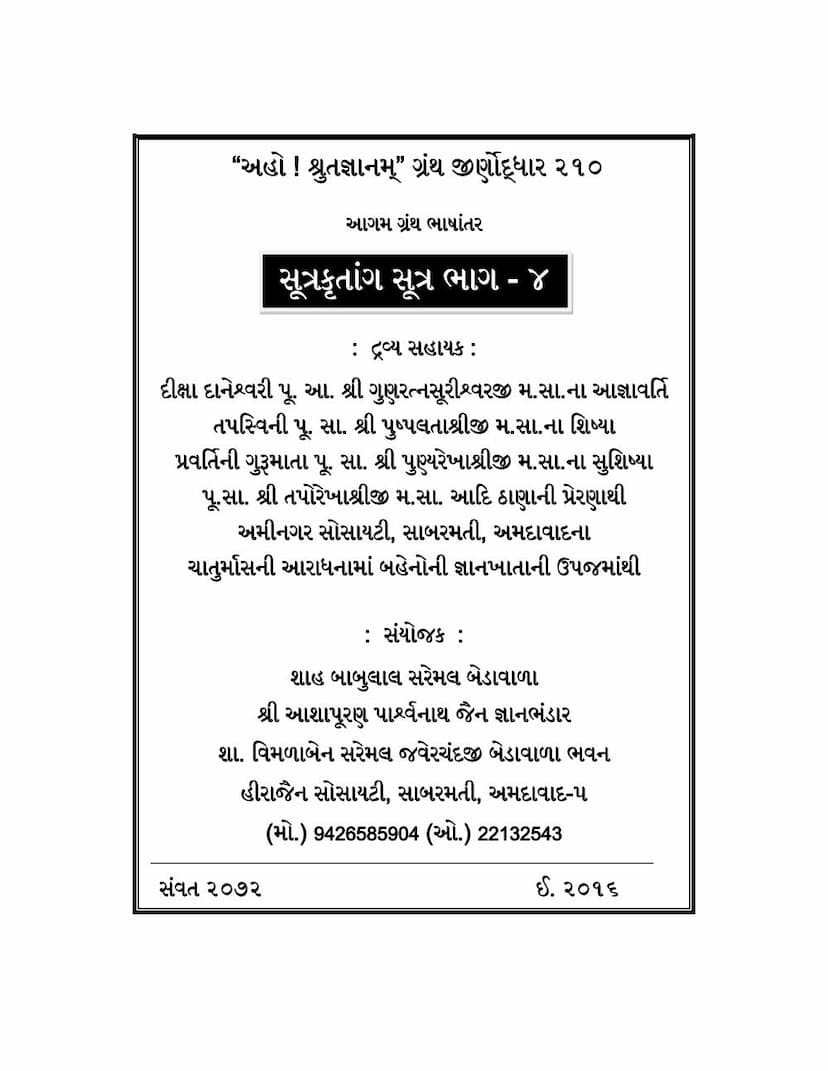

The document appears to be a publication from the "Aho Shrutgyanam Granth Jirnoddhar" (Preservation of Sacred Knowledge) initiative, specifically the 210th publication in the series. It is a Gujarati translation and commentary on a portion of the Sutrakritanga Sutra, specifically Part 04 of the second Skandha, focusing on the Pundarika Adhyayana (Chapter). The publisher is Mohanlal Jain Shwetambar Gyanbhandar, and the publication date is Sambat 2072 (2016 CE). The catalog link points to a digital archive of Jain scriptures.

The text highlights the effort to digitize and preserve ancient, often rare, Jain books, making them accessible through DVDs and online platforms like www.ahoshrut.org. This particular volume is part of a larger project that has digitized and cataloged numerous Jain texts, as evidenced by the extensive lists on pages 2 through 10.

Key Content of the Sutrakritanga Sutra Part 04 (Focusing on Pundarika Adhyayana):

The provided pages delve into the Seventeenth Chapter of the Second Skandha, titled "Shri Pundarika Adhyayana." The author, Muni Manek, has translated and provided commentary on this chapter.

Core Themes and Concepts:

- The "Pundarika" Analogy: The central theme revolves around the Pundarika (lotus) flower and its symbolic meaning in Jain philosophy. The Pundarika is used as an analogy to represent the ultimate goal of Moksha (liberation).

- Purity and Detachment: The lotus, growing in muddy water yet remaining pure and untouched by the mud, symbolizes the soul that can traverse the cycles of Samsara (worldliness) without being tainted by worldly desires and attachments.

- Attraction of the Pure: The lotus's beauty and fragrance attract, similarly, a pure and detached soul can attract others towards the path of liberation.

- The Ideal Preacher/Soul: The commentary emphasizes that an exponent (teacher) must first achieve a state of detachment (Vitraag) from worldly allurements before they can guide others, especially those in positions of power like kings.

- Understanding Different Philosophical Viewpoints (Nayas): The chapter addresses the importance of understanding various philosophical schools (Nayas) and their respective viewpoints. It mentions the need to analyze how different viewpoints lead to their respective conclusions, understand their reasoning, and then offer a synthesized explanation to guide individuals towards the right path. The text mentions discussions on viewpoints such as:

- Pancha Mahabhuta (Five Great Elements) theory: The belief that the universe is composed of only five elements.

- Ishvara as the cause of the world: The concept of God as the creator.

- Niyati (Fate/Destiny): The belief that everything is predetermined.

- Jain perspective: Contrasting these views with the Jain understanding of soul (Jiva), non-soul (Ajiva), and their various classifications.

- The Nature of Actions and Consequences: The text discusses the importance of righteous actions (Kriya) and the consequences of actions, both positive (Karma bandha leading to good destinations) and negative (Karma bandha leading to suffering).

- Moksha as the Goal: The ultimate aim is to attain Moksha through correct understanding and practice.

- The Role of Non-violence (Ahimsa): Ahimsa is highlighted as a paramount principle to be followed.

- The Importance of Self-Purification: The need for the preacher to purify their own soul before imparting teachings is stressed.

- Stages of Spiritual Progress (Guna Sthanas): The text briefly touches upon the fourteen Guna Sthanas (stages of spiritual development), emphasizing the subtlety of the highest stages and their relevance in the context of spiritual progress.

- The Distinction between Householders and Monastics: The text differentiates between the conduct and vows of householders (Grihastha) and monastics (Sadhu). It notes that even householders who have a desire for spiritual progress but lack the full capacity for complete renunciation (Samyak Darshana) can be considered as "Deshavirati" (partial renunciation) and are on the path of liberation.

- The Four Purusha Types and their Teachings: The latter part of the provided pages details four types of individuals and their philosophical stances, which the Jain monks (especially the fifth type, the Bhikshu/mendicant) must understand and counter:

- Kayatika (Body-centric): Believes the body is the soul.

- Panchamahabhautika (Five-elemental): Believes the universe and existence are reducible to five elements.

- Ishwarakaranika (God-centric): Believes God is the sole creator and controller.

- Niyativadi (Fatalist): Believes everything is predetermined by fate.

- The Pundarika Analogy in Detail: The chapter elaborates on the Pundarika analogy through a narrative.

- The Lotus Pond: A beautiful lotus pond is described, filled with various lotuses.

- The Four Men: Four men, each from a different direction, come to pluck the finest lotus. Each man, despite their proclaimed strength and wisdom, gets stuck in the mud and cannot reach the lotus. This illustrates the futility of worldly efforts without the right spiritual understanding.

- The Fifth Man (The Bhikshu/Mendicant): A mendicant, detached from worldly desires and equipped with true knowledge, observes the plight of the four men. Instead of getting stuck in the mud, they approach the lotus with understanding and detachment, and the lotus comes to them. This signifies the power of true spiritual knowledge and detachment in achieving liberation.

- The Teaching: This story serves as a teaching that worldly efforts without spiritual grounding lead to entrapment, while true spiritual understanding and detachment lead to the ultimate goal. The mendicant's success highlights the importance of understanding the true nature of reality and acting accordingly.

- Detailed Explanations of Kriya Sthanas: The text then moves on to the Kriyasthan Adhyayana (Chapter on Stages of Action). This chapter focuses on the concept of Kriya (action) and its role in bondage and liberation. It lists and explains thirteen Kriya Sthanas:

- Artha Danda (Meaningful punishment/action)

- Anartha Danda (Meaningless punishment/action)

- Hinsa Danda (Action causing violence)

- Akasma Danda (Accidental action)

- Drishti Viparyas Danda (Action based on wrong perception)

- Moshvratika (Falsehood)

- Adinnadanvratika (Stealing)

- Adhyatmavratika (Internal actions/thoughts)

- Manvratika (Pride/Arrogance)

- Mitradosh (Friend's fault/Enmity)

- Mayavratika (Deception)

- Lobhavratika (Greed)

- Iryavahika (Careful movement)

Each of these Kriya Sthanas is explained with its nuances and implications for spiritual progress and bondage. The text emphasizes that while some actions are inherently harmful, others are more subtle and may arise from lack of awareness or attachment. The importance of careful and conscious action (like Iryavahika) is highlighted.

Commentary and Presentation:

- The text includes detailed explanations and interpretations of the Sutras, often citing specific verses from the Niryukti (a commentary on the Sutras).

- The language is Gujarati, with a clear focus on explaining the philosophical concepts in a way that is accessible to the reader.

- The introductory pages list a vast collection of other Jain texts that have been digitized as part of the "Aho Shrutgyanam" project, showcasing the extensive scope of this preservation effort.

- The footnotes and cross-references suggest a scholarly approach to presenting the text.

- The preface by Muni Manek provides context and the philosophical importance of the Pundarika Adhyayana.

In essence, this part of the Sutrakritanga Sutra, through the Pundarika analogy and the Kriyasthanas, aims to guide the practitioner towards understanding the nature of actions, their consequences, and the correct path to liberation by emphasizing detachment, right knowledge, and ethical conduct, while also refuting various non-Jain philosophical systems.