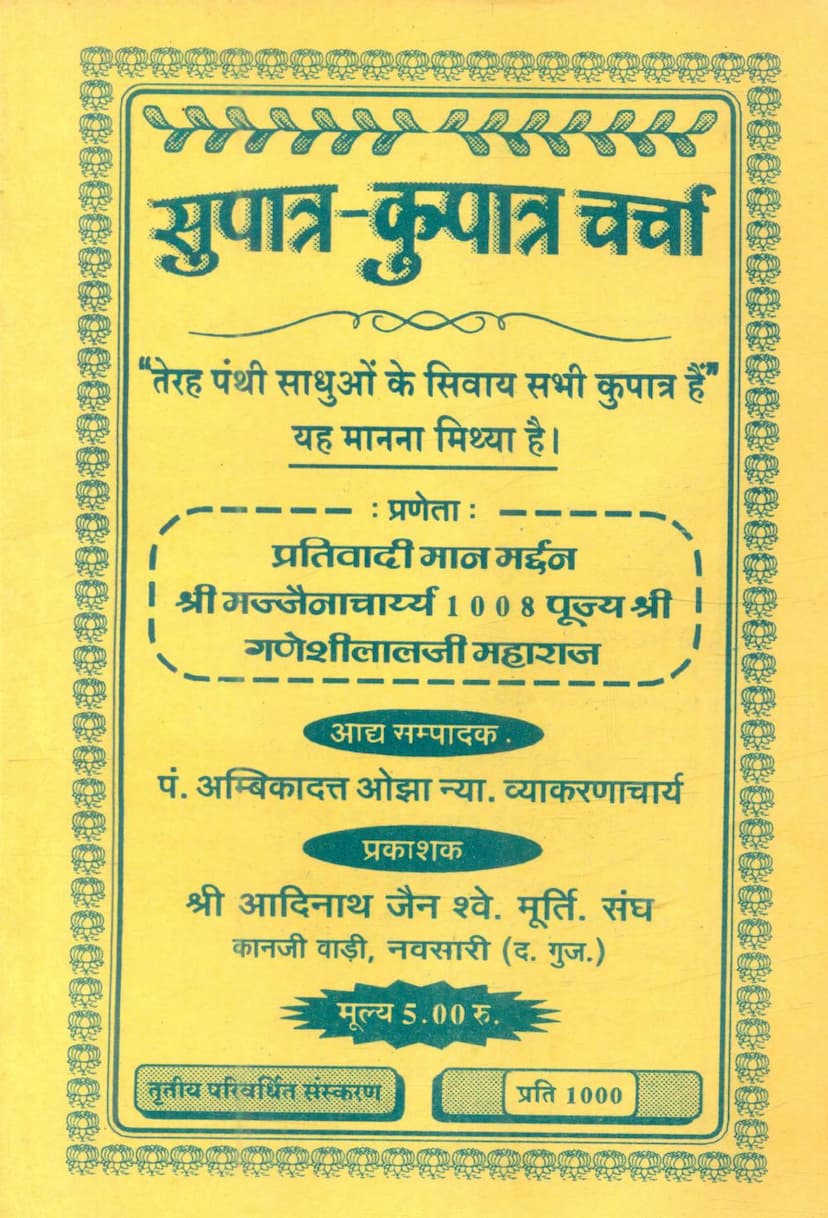

Supatra Kupatra Charcha

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Supatra Kupatra Charcha" by Ambikadutta Oza, based on the provided pages:

The book "Supatra Kupatra Charcha" (Discussion on Worthy and Unworthy Recipients), authored by Pt. Ambikadutta Ojha and published by Shri Adinaath Jain Shw. Murti. Sangh, challenges the central tenet of the Terapanth sect within Jainism, which asserts that "Except for the Terapanthi saints, all others are unworthy." The book strongly refutes this claim as a falsehood.

Core Argument and Context:

The book begins by highlighting that the majority of religious traditions worldwide, including Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity, Parsiism, and Islam, agree on the principles of compassion and charity. These faiths believe in alleviating the suffering of others and aiding those in distress. Jainism, too, aims for people to understand their duties towards one another, embodying the principle of treating others as one would wish to be treated.

However, the Terapanth sect, according to the book, stands in stark contrast. It uniquely posits that protecting a dying being and assisting the poor, distressed, lame, and disabled through food and clothing is considered an absolute sin. Their sole belief is that only Terapanth saints are worthy recipients of charity. Giving to anyone else is deemed an absolute sin, equivalent to consuming meat or engaging in vices.

The author criticizes the Terapanth for subtly altering their language over time. When questioned, they might refer to charitable acts as worldly duties. The book vehemently argues against the Terapanth's view that supporting laypeople (avrati, asanyati) is sinful because they might commit future transgressions. The book posits that our duty is to act with a pure heart in providing assistance, and the future actions of the recipient are not our responsibility.

Origin and Development of the Terapanth Sect:

The book traces the origin of the Terapanth sect to a figure named Bhikhaji. Bhikhaji, an Oswal by caste from the Marwar region, received initiation in Samvat 1808 from Acharya Shri Raghunathji Maharaj of the Bais sect. While being taught the Bhagavati Sutra, Bhikhaji developed certain dissenting views. A devout follower, Samarthmalji Dhariwal, warned Acharya Raghunathji that Bhikhaji's opposing interpretations would bring shame to Jainism. However, the Acharya, citing the examples of Goshala and Jamali who later became adversaries of Lord Mahavir, continued teaching Bhikhaji.

After completing his studies, Bhikhaji was instructed to leave the Bhagavati Sutra behind but disobeyed, taking it with him. This act of perceived distrust led Bhikhaji to resolve to establish his own sect and discredit his guru. He began propagating his unconventional and anti-scriptural views, which included the assertion that saving a creature burning in fire, falling into a well, drowning in a pond, or falling from a height are all absolute sins. He also claimed that preaching religion for the peace of souls is not a Jain principle.

Key Doctrines and Criticisms of the Terapanth:

The book extensively details and critiques several core beliefs of the Terapanth sect:

- All beings are unworthy except Terapanthi saints: This is the central tenet being attacked. The book argues that the Terapanth considers everyone else a sinner and that assisting them, showing them respect, or paying them homage is a grave sin, akin to meat consumption and vices.

- Charity and Assistance to others are sins: The Terapanth considers it a sin to help the blind, lame, crippled, those afflicted by natural disasters, or those suffering due to political reasons. They also deem it a sin to assist students in schools and colleges, or to help patients in hospitals.

- Rejection of Compassion and Humanity: The book argues that this viewpoint leads to societal disorder, the decline of benevolence and respect, and a breakdown in moral values. It calls this a disgrace to Jainism, where irreligion is promoted in the name of religion and human civilization is being destroyed.

- Misinterpretation of Scripture: The book cites a work called "Bhram-Vidhvansan" by Jitimallji, the fourth successor of Bhikhaji, which allegedly supports Bhikhaji's views. The book counters these claims with arguments from prominent Jain Acharyas like Shri Jawahar Lalji Maharaj, who have written extensively refuting the Terapanth's doctrines.

- Unworthy as "Weapons of the Six Bodies": Jitimallji is quoted as calling beings other than saints as "weapons of the six bodies" and deeming their sustenance as sin. The book challenges this by pointing out that even worldly renunciates (sadhu) can be considered "beginners" in this context, yet the Terapanth considers them worthy.

- Charity to Brahmins is a sin leading to hell: Jitimallji is cited as stating that feeding Brahmins leads to hell, equating it with consuming meat or engaging in vices. The book strongly refutes this, arguing that Jainism's foundational texts promote compassion and helping others.

- Charity to Householders is a sin: The Terapanth considers giving to householders, even those who have taken vows (pratimadhari), as sinful. The book argues that this contradicts the praise given to householders in Jain scriptures.

- Questioning the Basis of "Worthy" and "Unworthy": The book criticizes a contemporary discussion by a Terapanthi saint, Kundanalji, which raises questions about the merit or sin in various acts of charity and social service. It accuses the Terapanth of providing evasive answers and creating their own criteria for "worthy" and "unworthy" that are not found in Jain scriptures.

- Contradiction in Terapanth Doctrine: The book highlights a significant contradiction: if the presence of the five cardinal sins (violence, falsehood, theft, incontinence, and possession) makes one unworthy, then even monks with certain "asravas" (influxes of karma) would also be unworthy. The book questions why the Terapanth considers monks worthy while labeling householders as unworthy based on similar grounds.

- Shastric Evidence for Householders' Worthiness: The book meticulously cites scriptural passages from texts like "Uvavai Sutra" and "Sutrakritanga" that praise householders (shravaks) for their virtues, adherence to dharma, and their role in the spiritual path. It argues that to call such individuals "unworthy" is a direct contradiction of Jain scripture and an insult to the teachings of the Tirthankaras.

- The True Spirit of Jainism: The book concludes by emphasizing that Jainism is fundamentally a religion of compassion and protection for all living beings. It quotes the Prashna Vyakaran Sutra, stating that the Jain Agamas were described by the Lord for the protection of all beings in the world. The book asserts that the Terapanth's exclusionary doctrine is a misrepresentation and a harmful invention.

Overall Message:

The book is a strong indictment of the Terapanth sect's core belief that only their saints are worthy recipients of charity. It argues that this doctrine is not only unscriptural and irrational but also detrimental to the very fabric of society, eroding compassion, family values, and human decency. The author calls upon readers to critically examine these teachings and adhere to the true spirit of Jainism, which emphasizes universal compassion and well-being. The book aims to expose the "poisonous belief" that leads to the breakdown of social order and the negation of core Jain principles.