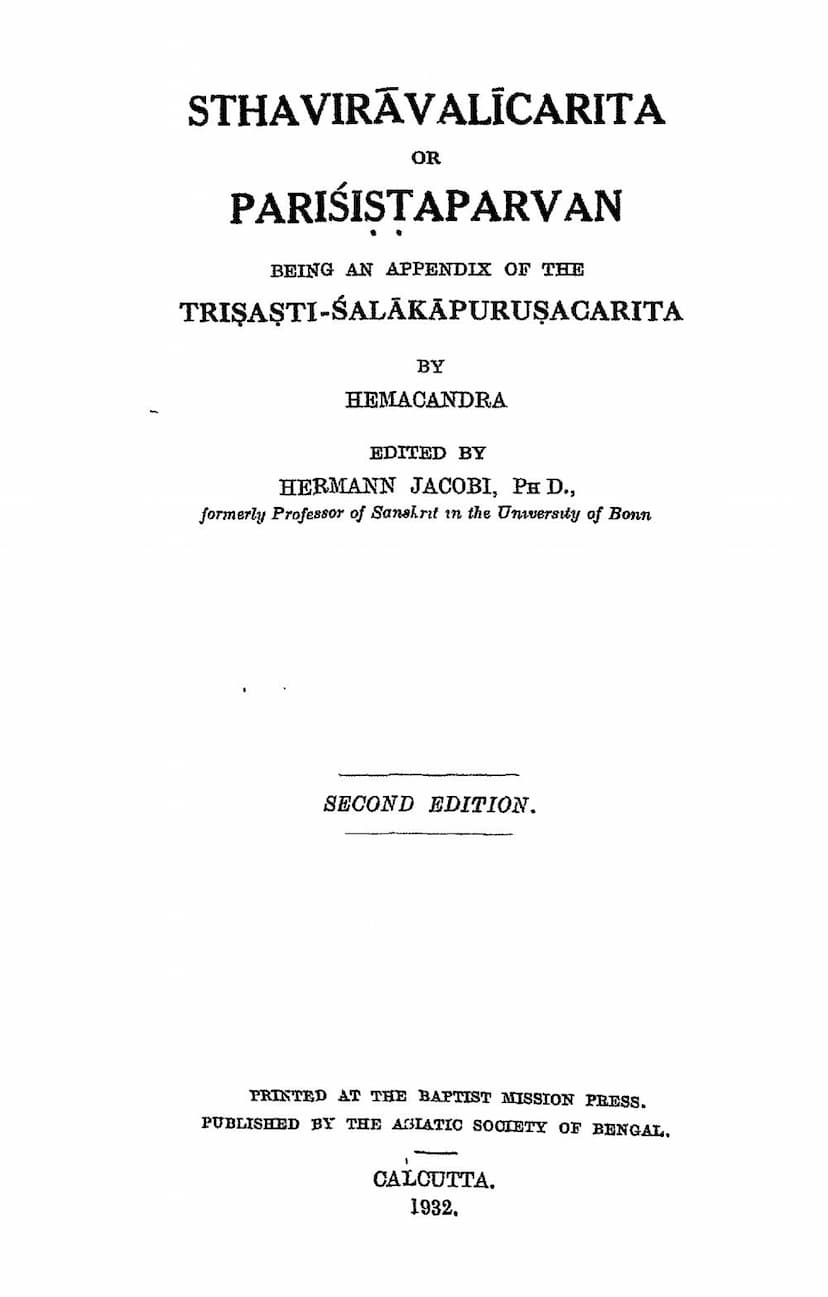

Sthaviravali Charitra Or Parisista Parva

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Sthavirāvalicarita" or "Pariśiṣṭaparvan" by Hemacandra, based on the provided text, edited by Hermann Jacobi:

Title and Context:

- Sthavirāvalicarita (Lives of the Patriarchs), also known by its more common title Pariśiṣṭaparvan (Appendix).

- It serves as an appendix or continuation to Hemacandra's larger work, the Trisasti-śalākāpuruṣacarita (Lives of the 63 Great Personages), which contains about 34,000 verses and details the lives of the 63 Salākāpuruṣas (24 Tirthankaras, 12 Cakravartins, 9 Vāsudevas, 9 Baladevas, and 9 Prativāsudevas).

- Both Śvetāmbara and Digambara traditions have accounts of the 63 Mahāpuruṣas up to Mahāvīra's nirvana. However, Hemacandra (a Śvetāmbara) is noted for continuing this history with an account of the patriarchs who followed Mahāvīra.

Content and Structure:

- The Sthavirāvalicarita is a legendary history of the Jaina patriarchs, arranged chronologically, from Jambu svāmin down to Vajrasena.

- It's structured into ten parvans (cantos) in the edition.

- The text is a compilation of various kathānakas (narratives or stories) drawn from earlier Jaina literature.

Sources:

- The introduction to the edition, by Hermann Jacobi, heavily relies on the analysis of Professor E. Leumann, who had a deep knowledge of Śvetāmbara legendary literature.

- The kathānaka literature, used by Hemacandra, is seen as layered:

- Sūtras: The earliest authoritative texts.

- Niryuktis: Systematical expositions of Sūtra subjects, often offering mere summaries of stories.

- Cūrṇis: Prakrit commentaries on Sūtras and Niryuktis, providing more detailed accounts.

- Ṭīkās: Explanations of Niryuktis, often using Cūrṇi texts and further developing the narratives.

- Hemacandra primarily drew upon Haribhadra's Ṭīkās on the Āvaśyaka Sūtra and, to a lesser extent, the Ṭīkā on the Daśavaikālika Sūtra.

- The Vāsudevahiṇḍi, a large work in Prakrit prose, is a significant source, especially for the first three cantos of the Parisista Parvan.

- The synoptic table provided in the introduction details the specific stories within the Parisista Parvan and their corresponding sources from the Vāsudevahiṇḍi and other kathānaka literature (like Āvaśyaka, Uttarādhyayana, Kalpa, and Niśītha Sūtras).

Historical Foundation and Chronology:

- The work is acknowledged as a legendary history, and the question of its historical foundation is addressed.

- The ancient Therāvalis (lists of elders/patriarchs) of the Śvetāmbaras are considered independent evidence supporting the historical character of the patriarchs and their succession order.

- There are two main lines of Therāvalis: one associated with the Nandi and Āvaśyaka Sūtras, and the other with the Kalpasūtra. These lines diverge after the eighth generation after Mahāvīra.

- The text discusses the dates of various schisms and patriarchs, identifying inconsistencies and suggesting that the early records might be imperfectly handed down, possibly with more patriarchs than listed in the Therāvali.

- A significant point of discussion is the chronology of Mahāvīra's nirvana. Hemacandra's work (Parisista Parvan VIII 339) places Candragupta's accession 155 years after Mahāvīra's liberation. This is supported by Bhadresvara's Kahāvalī, though general tradition places it 60 years later. The text discusses the implications for the dates of Buddha and Mahāvīra's nirvana, suggesting a corrected date of 477 BC for Mahāvīra's nirvana.

Bhadreśvara's Kahāvalī:

- The introduction also mentions Bhadreśvara's Kahāvalī, another work that covers similar ground.

- Bhadreśvara's work is described as a continuation that goes beyond Hemacandra's, including the lives of "Yugapradhānas" (leaders of eras) from Kālaka to Haribhadra.

- Bhadreśvara's work is considered to have fewer literary merits, being more of a collection of materials, whereas Hemacandra's Sthavirāvalicarita reads like a connected history in fluent Sanskrit verses and a spirited kāvya style, which led to its superseding the older work.

Hemacandra's Compositional Style and Innovations:

- Hemacandra's śloka (verse) usage is noted as peculiar and innovative, often deviating from classical rules regarding syllable patterns and cæsura.

- These irregularities are attributed to Hemacandra's intention to create a more flexible poetic style, possibly to facilitate the literary activities of the Jain community.

- However, his innovation was not widely adopted by subsequent Jain poets, who largely reverted to classical models.

- The text also points out "literary defects" like the use of meaningless syllables (arthapūraṇa) to fill metrical requirements, which Hemacandra himself discusses in his Kāvyānuśāsana.

- Jacobi qualifies his earlier criticism, stating that while Hemacandra's style was innovative and not always perfectly polished, it should not overshadow the undeniable excellence of his work, especially when compared to older sources like Bhadreśvara's Kahāvalī. Hemacandra aimed to provide a Jain substitute for the great epics of Brahmanical culture.

Key Patriarchs and Narratives:

The introduction and the canto summaries provide a glimpse into the narratives within the Pariśiṣṭaparvan:

- Canto 1: Begins with the description of Magadha and Rajagṛha, King Śrenika, and Mahāvīra's preaching. It includes the story of Prasannacandra (who became an ascetic) and his son Valkalacīrin, who was raised in ignorance of women and later brought to civilization.

- Canto 2: Continues with stories like Vidyunmālin, Anādhṛta, Prabhavā, and Sambhūta-vijaya. The story of Jambu's birth as the son of Rsabhadatta and Dharini, his betrothal to eight girls, and his subsequent renunciation is a major narrative. It also includes tales illustrating moral lessons, like the man in the well, the courtesan who married her son, and the cunning woman with the anklet.

- Canto 3: Continues with stories like Maheśvaradatta, Baka the farmer, the monkey and bitumen, the three friends (Sahamitra, Parvamitra, Prāṇāmamitra), the story-inventing girl, and Lalitāṅga.

- Canto 4: Focuses on King Kūṇika, Sudharman's preaching, Jambu's history, and his appointment of Prabhava as his successor.

- Canto 5: Details the conversion of Sayyambhava from Vedic ritualism to Jainism, and the story of his son Manaka, who eventually composed the Daśavaikālika Sūtra.

- Canto 6: Describes the lives of Bhadrabāhu's disciples, the founding of Pāṭaliputra, the story of Aṇikāputra, and the rise of King Nanda.

- Canto 7: Continues with the stories of Kalpa (who had precocious knowledge), the minister Kalpa under King Nanda, and the events leading to the downfall of the Nanda dynasty.

- Canto 8: Covers the succession of Nanda kings, the ministers who were descendants of Kalpa, the stories of Śakatāla and Sthūlabhadra, Vararuci, and the minister Śriyaka.

- Canto 9: Continues with the stories of Śthūlabhadra's austerities and his interactions with the courtesan Kośā, the story of Canakya and Candragupta, their rise to power, and the eventual poisoning of Candragupta's successor, Bindusara.

- Canto 10: Details the lives of Sthūlabhadra's disciples, Mahāgiri and Suhastin, their spiritual pursuits, and their interactions with various individuals and kings, including King Samprati.

- Canto 11: Continues the narratives involving Mahāgiri and Suhastin, King Samprati's patronage of Jainism, and stories illustrating spiritual progress and perseverance.

- Canto 12: Focuses on Vajrasvāmin and his lineage, his disciples like Dhanagiri, Ārya Samita, and Vajra, and stories highlighting their spiritual prowess and the conversion of various individuals.

- Canto 13: Continues with Vajrasvāmin's travels, his encounters, and stories of patrons and disciples. It details the life of Ārya-rakṣita, his pursuit of knowledge, and his interactions with Vajrasvāmin.

Overall Significance:

The Pariśiṣṭaparvan is a vital source for understanding the legendary history of the Śvetāmbara Jaina tradition. It not only continues the hagiographical narrative of the Salākāpuruṣas but also provides detailed, often allegorical, stories that illustrate Jaina doctrines, ethical principles, and the lives of important spiritual leaders and patrons. The work showcases Hemacandra's skill in weaving together diverse narrative threads into a coherent and engaging epic poem, contributing significantly to the literary and religious landscape of Jainism.