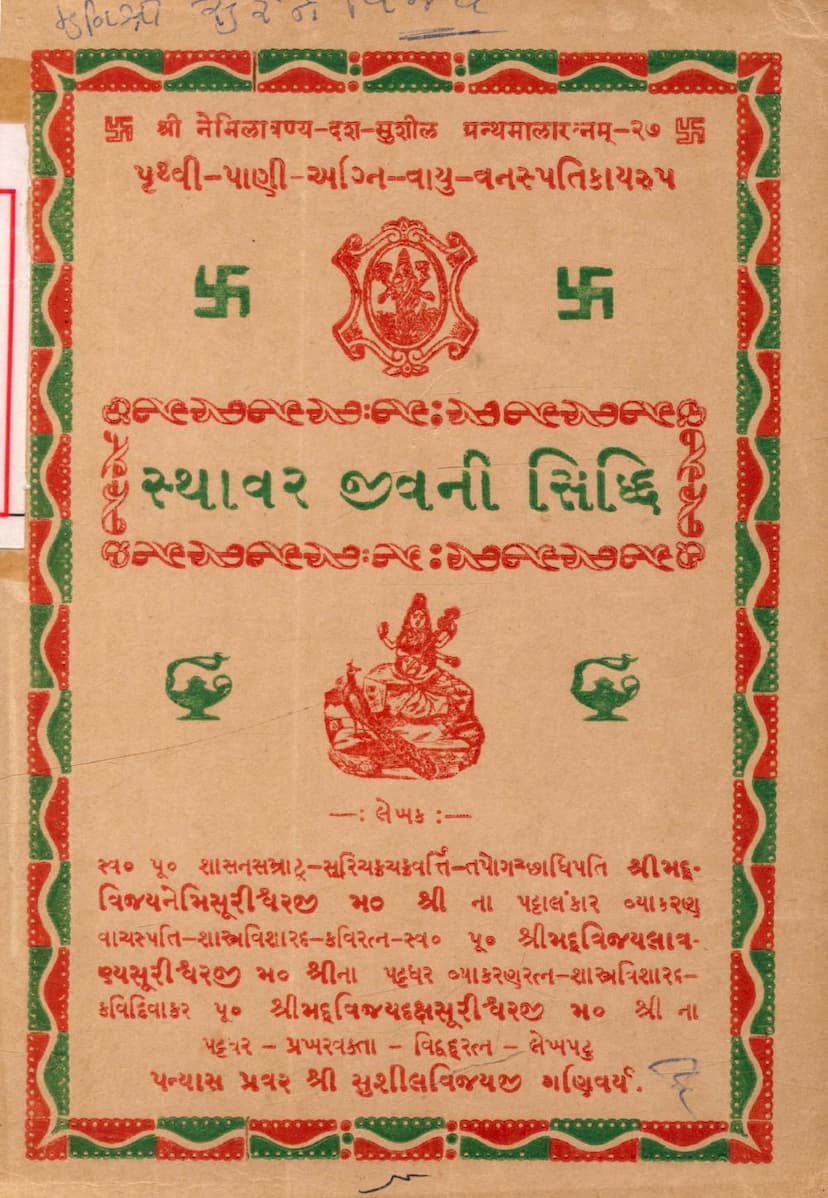

Sthavar Jivni Siddhi

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Sthavar Jivni Siddhi" by Sushilvijay, based on the provided pages:

Title: Sthavar Jivni Siddhi (The Attainment/Realization of Stationary Souls)

Author: Shri Sushilvijay Ganivarya (Disciple of Shri Vijaydaksh Surishwarji, who was the disciple of Shri Vijaylavanya Surishwarji, who was the disciple of Shri VijayNemi Surishwarji).

Publisher: Shri Gyanopasak Samiti.

Core Theme: The book aims to explain and prove that souls exist in stationary beings (Sthavar Jiva) which include Earth (Prithvi), Water (Pani), Fire (Agni), Air (Vayu), and Plants (Vanaspati). It emphasizes the importance of non-violence (Ahimsa) towards these beings and encourages minimizing harm.

Content Overview:

The book systematically delves into each category of stationary souls, providing evidence and reasoning for their existence as living beings.

-

Introduction to Jiva (Souls): The text begins by classifying souls into two main categories: Siddha (liberated souls) and Samsari (worldly souls bound by karma). Samsari souls are further divided into Tras (mobile) and Sthavar (stationary) souls. Tras souls can move voluntarily, while Sthavar souls are fixed in their place. Sthavar souls are exclusively one-sensed (Ekendriya).

-

Prithvi Kaya (Earth Souls):

- Proof of Life: The text argues that Earth souls are living beings because they grow, and their bodies, though sometimes appearing inanimate like rocks or minerals, exhibit signs of consciousness. Analogies are drawn to humans in a stupor or unconscious state, and to the growth of human body parts, to illustrate the presence of consciousness in Earth souls.

- Examples: Growth in plants is compared to the growth within the Earth body. The text mentions that substances like salt, coral, and stones grow from their respective sources. It also uses the example of mercury and its supposed "mating instinct" when exposed to a virgin girl as evidence of its animate nature.

- Classification: Earth is divided into subtle (Sukshma) and gross (Badar) Earth souls. Gross Earth souls are further categorized into portable (Pasansan) and non-portable (Apasansan) based on whether they complete all four life-sustaining processes (ahara, sharir, indriya, shwasochhvas) before death. The book lists various types of substances that fall under Earth souls, including crystals, gems, minerals, metals, salts, clays, stones, and more, citing specific verses from Jain scriptures (Vavavavar Prakaran).

-

Ap Kaya (Water Souls):

- Proof of Life: The text asserts that water contains souls, citing phenomena like water being warmer in winter (indicating internal heat), steam rising from water, and the fluid state of conception in animals and birds. Analogies are made to bodily fluids in living beings.

- Scientific Reference: It mentions a scientific book titled "Siddhapadarth Vigyan" which reportedly observed 36,450 moving organisms in a single drop of water under a microscope.

- Classification: Water is also divided into subtle and gross, and portable and non-portable categories, similar to Earth souls. Various forms of water like well water, rainwater, dew, ice, hail, fog, and solid water masses are described. The text clarifies that the observed microscopic organisms are two-sensed (Dvi-indriya) and not water souls themselves, but the water itself is composed of countless souls. It distinguishes between sentient (Sachit) and inert (Achit) water, explaining how water becomes inert after boiling and how certain substances can keep it inert for longer.

- Usage: It stresses the importance of using water with utmost care and restraint, advising against unnecessary wastage.

-

Agni Kaya (Fire Souls):

- Proof of Life: Fire is described as a living being because it possesses inherent heat and light, requires sustenance (like fuel), grows when fed, needs air to exist, and can be extinguished. Its growth, dependence on fuel, and susceptibility to being put out are compared to the life cycle of living beings.

- Classification: Fire souls are categorized into gross and subtle, and portable and non-portable. Various forms of fire are mentioned, including burning coals, flames, meteors, lightning, sparks, and fire generated by friction. The text notes that lightning is a potent form of fire and that artificially generated electricity is also considered sentient.

- Usage: The book warns against the unnecessary use of fire and the violence inflicted upon fire souls through cooking, burning, and other activities, urging for caution.

-

Vayu Kaya (Air/Wind Souls):

- Proof of Life: Air is considered animate because it moves spontaneously, can be perceived through touch (warm or cold), and its presence is felt even when invisible. It can influence objects and be affected by other forces.

- Classification: Air is divided into gross and subtle. Various types of air currents are described, such as ascending air, descending air, whirlwinds, strong winds that uproot trees, gentle breezes, and roaring winds. The text also mentions stationary air beneath celestial bodies.

- Usage: The book advises mindful breathing and movement, as any action involving air can cause harm to air souls. It cautions against speaking with an open mouth or engaging in activities that disturb the air unnecessarily.

-

Vanaspati Kaya (Plant Souls):

- Proof of Life: This section provides extensive evidence for life in plants, drawing parallels with human and animal life:

- Growth and Death: Plants grow and die like other beings.

- Sensation: Despite having only the sense of touch, plants are said to experience sensations akin to all five senses. They respond to sounds, sights, smells, tastes, and touches.

- Emotions and Instincts: The text claims plants exhibit human-like emotions and instincts such as love (passion), joy, shame, fear, desire, anger, pride, deceit, greed, and disease. Examples are given of trees flowering when serenaded, plants wilting at a touch (like the "shy plant"), trees bearing fruit when embraced, trees responding to certain sounds, and plants seeking support. It also mentions trees and plants having seasons for growth, flowering, and fruiting.

- Reproduction and Life Cycle: Plants have birth, growth, and death. Some plants have distinct male and female forms (e.g., papaya).

- Scientific Support: The text references the work of Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose, who reportedly proved through experiments that plants have feelings and reactions similar to animals.

- Classification: Plants are divided into two main categories:

- Sadharan Vanaspati Kaya (Collective/General Plant Souls): In these, one body contains infinite souls. Examples include roots of sugarcane, onions, potatoes, various vegetables, herbs, and even microscopic organisms on surfaces. These are described as more delicate and less sentient than Pratyek Vanaspati.

- Pratyek Vanaspati Kaya (Individual Plant Souls): In these, one body contains one soul. This includes trees like mango, banyan, fruit-bearing plants, flowering plants, and individual blades of grass.

- Usage: The book strongly emphasizes avoiding harm to plants, highlighting the immense violence caused by uprooting, cutting, harvesting, and consuming them. It urges extreme caution in the use of plant products.

- Proof of Life: This section provides extensive evidence for life in plants, drawing parallels with human and animal life:

Key Jain Principles Highlighted:

- Ahimsa (Non-violence): The central tenet of the book is the imperative of non-violence towards all forms of life, including the subtle and seemingly inanimate.

- Anekantavada (Multiple Perspectives): The book uses reasoning and analogies to present the Jain perspective on the existence of souls in all beings.

- Karma and Rebirth: The concept of soul's journey through different life forms, including the Sthavar category, is implicitly present, suggesting that actions (karma) lead to rebirth in these forms.

- Jayaṇā (Carefulness/Caution): For lay followers who cannot completely avoid harming Sthavar souls, the text advocates extreme caution and mindful consumption, minimizing any accidental violence.

Purpose of the Book:

The book serves as an educational tool to deepen understanding of Jain philosophy regarding the existence of souls in stationary beings. It aims to cultivate compassion, encourage mindful living, and guide readers towards reducing violence in their daily lives, particularly in dietary habits and resource utilization.

Overall Tone:

The book is instructional, persuasive, and deeply devotional in its presentation of Jain ethics and cosmology. It aims to awaken the reader's awareness of the omnipresence of life and the spiritual responsibility to uphold non-violence.