Siddhartha

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Siddhartha" by Muni KalyanKirti Vijay, based on the provided pages:

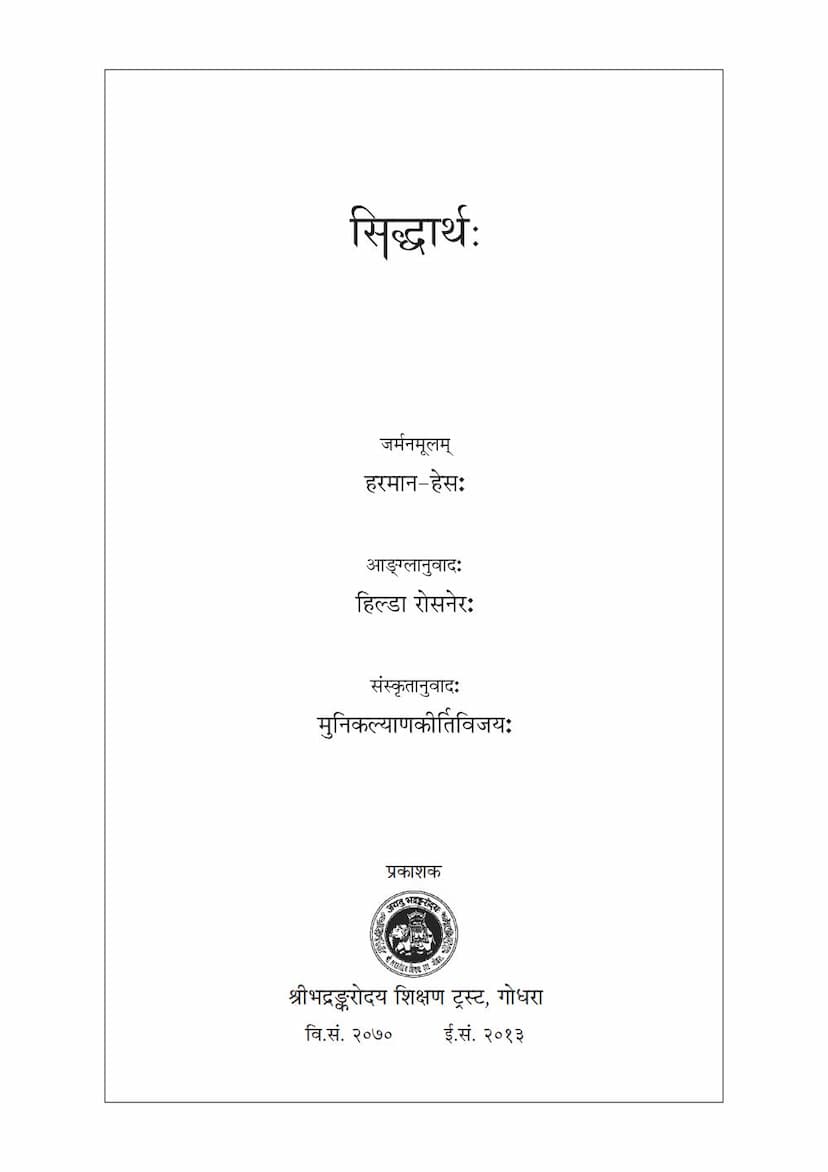

This Sanskrit text, "Siddhartha," is a translation of Hermann Hesse's novel, originally in German and then translated into English by Hilda Rosner. The Sanskrit translation is by Muni KalyanKirti Vijay and published by Shri Bhadrankaroday Shikshan Trust, Gondal, in 2013.

The preface highlights the unique achievement of Western philosophers and writers who deeply engage with and synthesize Eastern philosophical and spiritual traditions into their literature. It notes that German Nobel laureate Hermann Hesse was such a writer, effortlessly integrating Western and Eastern philosophies and possessing a pure, innate spiritual understanding. The preface then delves into Hesse's background, mentioning his German father (a religious scholar), French mother, and maternal grandfather, a Christian missionary who also served in India, learned over thirty Indian languages, and deeply studied Eastern philosophies. Both of Hesse's parents also worked as missionaries in India. This upbringing provided Hesse with a profound exposure to both Western (Christianity) and Eastern (Indian philosophies) thought from childhood, fostering in him a peaceful disposition and strong spirituality. Hesse began his literary career in 1899, moved to Switzerland in 1912, where he lived until his death in 1962, and received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1946. His works are globally recognized and translated, earning him admiration from spiritual scholars worldwide. One scholar even stated that Hesse was a "Veda-knower" in understanding the cycle of existence and its liberation, similar to the ancient sages.

The core message of Hesse's literature, as conveyed in the preface, emphasizes that:

- True religion cannot be taught externally; it arises from within and is realized through personal experience.

- Knowledge can be gained through instruction, but wisdom cannot.

- Truth is not found by following others but through self-discovery. Words are inadequate to express ultimate truth, which is experiential.

- Love is the highest value in the world.

- Every human's primary duty is to discover their own path.

The novel "Siddhartha," written in 1923, explores themes of Brahmanical, Shramana, and Buddhist traditions, Indian lifestyle, pure spiritual philosophy, and self-reliance. The preface mentions that the novel has been translated into many world languages, including an English translation by Hilda Rosner in 1953, and four translations into Gujarati. The Sanskrit translator, inspired by the Gujarati translations, undertook the current Sanskrit translation based on the English version. The translation was reviewed and refined by respected gurus Acharya Shri Vijay Sheel Chandra Suri, Upadhyay Shri Bhuvan Chandra Ji Maharaj, and Muni Shri Kirti Chandra Ji Maharaj. The translator expresses gratitude for their guidance, stating that this translation work has been a valuable learning experience, imparting important life lessons and enabling the experience of constant joy and enthusiasm. The preface also acknowledges the individuals who contributed to the book's production, including the typesetters, the artist (Nainesh Saraiya), and the printing designer. The translator hopes this Sanskrit version will encourage Sanskrit scholars to engage with global literature.

The first part of the text, titled "The Brahmin's Son," introduces Siddhartha, the son of a respected Brahmin, raised in comfort and love with his friend Govinda. Siddhartha is depicted as intelligent, curious, and already engaged in deep contemplation and the practice of yoga, including the chanting of "Om." He experiences a profound sense of unity with the universal soul. His parents are proud of his intellect and demeanor, and Govinda is deeply devoted to him, admiring his wisdom, character, and strength of will.

Despite being loved and admired, Siddhartha is not content. He is troubled by the cycles of nature and the rituals and teachings of his tradition. He questions the efficacy of baths and sacrifices in cleansing the soul or bringing true happiness. He grapples with fundamental philosophical questions about creation, the nature of Brahman, the divinity of the gods, and the true path to the self. He realizes that no one, not even his learned father or the Brahmins, can show him the ultimate truth or guide him to the inner self.

Siddhartha's internal struggle intensifies as he contemplates the limitations of knowledge and ritual. He finds intellectual pursuits unsatisfying and feels an inner restlessness. He recognizes that even the teachings of the Upanishads, while profound, are not enough if not realized through experience. He feels that the Brahmins, despite their vast knowledge, have not truly attained the ultimate truth they speak of. This deep dissatisfaction fuels his resolve to seek a different path.

The narrative then describes a pivotal moment where Siddhartha decides to become a Samana (ascetic). He communicates this decision to his father, who is initially silent and then expresses his inability to hear such a proclamation further. Siddhartha remains resolute, and his father, though disappointed, ultimately permits him to go and tell his mother, seek her blessing, and then depart. Siddhartha's departure is marked by the quiet support of Govinda, who resolves to follow him in whatever capacity possible.

The story then shifts to Siddhartha's life as a Samana. He renounces his worldly possessions, dons simple saffron robes, and adopts an austere lifestyle of one meal a day, often engaging in prolonged fasts. His body becomes emaciated, his nails grow long, and his beard becomes rough. He cultivates an indifference to sensory experiences, viewing the world with detachment. He observes the superficiality and transient nature of worldly pleasures and realizes that all beings are heading towards inevitable destruction.

Siddhartha's primary goal becomes "the attainment of emptiness"—emptiness of desire, dreams, attachments, duality, and ultimately, the dissolution of ego. He believes that only by conquering the self and annihilating the ego can the true, hidden essence of life—the highest truth—be revealed. He practices extreme asceticism, enduring heat, cold, hunger, thirst, and physical pain with unwavering determination. He also learns control over his senses, mind, and breath, even managing to slow and control his heartbeat. He delves into advanced yogic practices and achieves mastery over his body and mind. He also explores the practice of "perkāyapravēśa" (entering another's body), experiencing life as a bird and a decomposing animal, thus gaining profound insights into the cycle of life, death, and suffering.

Through his ascetic practices, Siddhartha learns various methods of self-annihilation and mastery. He achieves control over hunger, thirst, and physical exertion. He also masters the control and stabilization of the mind through meditation. However, he realizes that these paths, while leading to emptiness and samadhi, ultimately lead him back to his former state. He finds himself returning to his physical body, to the cycle of existence, and to the suffering of life.

Meanwhile, Govinda, who follows Siddhartha, mirrors his efforts and also strives for spiritual realization. They communicate little, primarily focusing on their respective practices. During one alms-seeking journey, Siddhartha questions Govinda about their progress, expressing his doubt that they have achieved their goals. Govinda acknowledges their learning but praises Siddhartha's rapid progress, noting his admiration from elder Samanas and the possibility of him becoming a great soul. Siddhartha, however, dismisses the learned teachings of the Samanas, stating he could have learned the same superficialities from worldly people in a tavern. He questions the efficacy of meditation, body-annihilation, and asceticism, viewing them as mere escapes from the self and temporary relief from suffering, comparing it to the intoxication of a drunkard seeking brief oblivion. Govinda counters that Siddhartha is not a mere drunkard, as true escape leads to self-understanding, not just temporary relief. Siddhartha admits his uncertainty about his own future but feels disconnected from wisdom and Nirvana, like an embryo in the womb.

The narrative then describes Siddhartha and Govinda's growing disillusionment with the Samana path. Siddhartha expresses that the teachings of the Samanas are not leading him to his goal and that he could have gained similar superficial knowledge from worldly individuals. He finds the rigid practices and doctrines unfulfilling and questions the purpose of their asceticism. Govinda, while acknowledging Siddhartha's spiritual potential, struggles to comprehend his radical views.

Chapter 3: Gautam

The story then shifts to Siddhartha and Govinda's journey to Shravasti, where the enlightened Buddha, Gautam, resides. They learn of Buddha's presence in Jetavana, a grove donated by the wealthy Anathapindika. Upon arriving in Shravasti, they are offered alms by a householder, from whom they learn Buddha's location. Govinda is eager to meet Buddha, but Siddhartha remains contemplative, his attention drawn to Buddha's physical presence rather than his teachings.

They observe Buddha, dressed in saffron robes, walking through the city for alms, radiating peace and detachment. Siddhartha is struck by Buddha's demeanor, finding it devoid of desire, pretense, or effort, radiating only peace, fulfillment, and innate well-being. He notes that Buddha's every movement, his gaze, his hands, and his entire being emanate ultimate peace and perfection. Govinda is also deeply impressed and recognizes Buddha, despite his simple appearance.

They follow Buddha to Jetavana, where they are struck by the peaceful atmosphere and the disciplined lives of Buddha's disciples. They note that even Buddha himself engages in daily alms-seeking. Siddhartha, observing Buddha, feels a profound connection, a recognition that this is the one he has been seeking. However, he doesn't feel the urge to listen to Buddha's teachings, believing he has already grasped their essence. His attention is captivated by Buddha's physical presence—his hands, feet, and every gesture. He perceives a profound truth emanating from Buddha's very being.

Siddhartha conveys to Buddha his admiration for his teachings, which he finds clear and profound, explaining the interconnectedness of the world and the laws of cause and effect. However, he points out a perceived flaw: the concept of Nirvana, which breaks this fundamental cosmic order and introduces something new and unexplainable into the world. Buddha calmly acknowledges Siddhartha's insight and encourages him to be mindful of the traps of intellect and language. He clarifies that his teachings are not about understanding the universe but about liberation from suffering. Siddhartha expresses his respect for Buddha and his realization that no one can attain Nirvana through teachings alone, as it must be personally experienced. He then declares his intention to go his own way, not to seek another path or doctrine, but to find his own truth and perhaps face his own end. Buddha, with a gentle smile, simply acknowledges Siddhartha's determination.

Siddhartha perceives Buddha's interactions with his disciples and his serene presence as embodying a certain perfection that he himself strives for. He feels a sense of kinship with Buddha's teachings but also a need to chart his own course. Siddhartha believes he has already gained enough from the Samanas and that the path of external teachings is not his. He sees his own journey as one of self-discovery, not of following a guru. He leaves Jetavana with a profound experience of Buddha's presence but a commitment to his own independent search.

Chapter 4: Awakening

Leaving Jetavana, Siddhartha feels a profound sense of transformation. He realizes that his previous life has been shed, and he has entered a new phase of existence. He reflects on his journey and the lessons learned from various teachers, including his father, the Brahmins, the Samanas, and finally, Buddha. He acknowledges that while he has learned much, a fundamental gap remains—the true nature of his own self. He realizes that he has been seeking something beyond himself, escaping his own being, and that the true quest is within. He recognizes that the external world, which he once dismissed as illusion, is now perceived with newfound clarity and beauty, reflecting an inner reality.

Siddhartha contemplates the cycle of life, death, and rebirth, experiencing a profound awakening. He understands that the external world is a manifestation of his inner state and that true understanding comes from within. He recognizes that his pursuit of knowledge and spiritual enlightenment was, in a way, an escape from himself, an attempt to conquer or understand his own being. He realizes that the essence of life is not in external doctrines or teachers but in the direct experience of the self. He embraces the present moment and the interconnectedness of all things, finding beauty and meaning in the natural world.

He reflects on his past failures, his pursuit of external validation, and his struggle with attachment and desire. He understands that true liberation comes from within, through self-acceptance and the embrace of his own authentic nature. He finds a sense of peace and purpose in his own unique journey, realizing that his path is not to be found in following others but in the unadulterated experience of existence. He recognizes the profound influence of his experiences, including his encounter with the courtesan Kamala, and the ultimate meaning of his quest for self-realization.

Chapter 5: The Courtesan

Siddhartha, now transformed, encounters Kamala, a beautiful and skilled courtesan. He is struck by her beauty and the sophistication of her world, which contrasts sharply with his ascetic past. He admits his ignorance of the arts of love and seeks her tutelage. Kamala, amused by the shaven, poorly dressed Samana, initially finds him unsuitable for her refined lifestyle. However, she is intrigued by his earnestness and the profound transformation he seems to have undergone.

Siddhartha articulates his intention to learn from her, not out of lust, but as a means of understanding a different facet of life. He acknowledges his lack of wealth and suitable attire but expresses his strong desire to learn. Kamala, amused and somewhat intrigued, tests him with a poetic verse. Siddhartha, in response, composes a verse about Kamala, which she finds beautiful. This exchange leads to their first intimate encounter, where Siddhartha experiences the depths of human passion and the art of love from Kamala.

He learns from her that true pleasure is mutual and that love requires skill and understanding. He discovers the complexities of human relationships and the transactional nature of desires. Despite his initial ignorance, Siddhartha proves to be a quick learner, adapting to the world of wealth and pleasure. He begins to engage in commerce under the patronage of Kamaswami, a wealthy merchant, aiming to acquire wealth and further his connection with Kamala.

The narrative then shifts to Siddhartha's life as a wealthy merchant, driven by his desire for Kamala and the worldly pleasures she represents. He learns the art of business, accumulates wealth, and indulges in a life of luxury. However, despite his outward success, a sense of inner emptiness and dissatisfaction lingers. He realizes that material wealth and sensual pleasures, while enjoyable, do not bring true fulfillment. His encounters with Kamala, while teaching him about physical love and worldly sophistication, also highlight the transient nature of these experiences. He begins to question the meaning of his life and the true nature of happiness and enlightenment.

Chapter 6: Among the Common People

Siddhartha, now a wealthy and influential merchant, finds himself increasingly detached from his past spiritual aspirations. He lives a life of luxury, engaging in commerce, indulging in sensual pleasures, and participating in gambling and other worldly pursuits. He observes the common people with a mixture of amusement and pity, seeing their lives as driven by trivial desires and fleeting emotions. Yet, he also acknowledges a certain vitality and authenticity in their simple existence, a stark contrast to his own inner turmoil.

He reflects on his past journey, his encounters with various spiritual teachers, and his pursuit of enlightenment. He recognizes that his earlier ascetic practices, while disciplined, were ultimately an escape from himself. His life in the city, though filled with material comforts, leaves him with a growing sense of emptiness and discontent. He realizes that true happiness and peace cannot be found in external pursuits but must be cultivated from within.

Siddhartha's relationship with Kamala becomes a complex interplay of love, desire, and intellectual stimulation. He learns from her about the art of seduction, the nuances of human emotion, and the transactional nature of relationships. However, he also recognizes that Kamala, like himself, is seeking something more profound, a deeper connection beyond superficial pleasures.

During his travels and observations, Siddhartha encounters various people from all walks of life. He observes the struggles, joys, and follies of ordinary people, finding a strange fascination in their uninhibited embrace of life. He begins to question his own detachment and his judgmental attitude towards them. He realizes that even in their simplicity and perceived flaws, they possess a certain resilience and authentic connection to life that he lacks.

Siddhartha's internal conflict intensifies. He grapples with the meaning of his life, the pursuit of happiness, and the true nature of enlightenment. He recognizes that his journey has been one of seeking, and that the ultimate truth lies not in external doctrines but in his own inner experience. He begins to question the path he has taken and the validity of his worldly pursuits. He realizes that true fulfillment comes from understanding and embracing his own inner nature, not from seeking external validation or pleasure.

Chapter 7: The River

Siddhartha, now old and weary, returns to the river where he had once contemplated suicide. He feels a profound sense of emptiness and disillusionment. He has lived a life of luxury and pleasure but found no lasting peace or contentment. He reflects on his past, his pursuit of enlightenment, and his worldly experiences, realizing the futility of his endeavors. He feels a deep sense of regret and the weight of his past actions.

He contemplates the river, finding solace in its constant flow and eternal presence. He observes the river's journey, its power, and its interconnectedness with all of nature. He realizes that the river symbolizes the eternal cycle of life and the interconnectedness of all beings. He finds a profound spiritual truth in the river's continuous flow and its ability to embrace all that comes its way.

Siddhartha recognizes that the river represents a state of being beyond desire, attachment, and intellectual striving. It embodies acceptance, detachment, and an innate understanding of existence. He yearns to merge with the river's essence, to find peace in its eternal flow. He understands that true liberation lies in surrendering to the natural order of the universe and finding contentment in the present moment.

Chapter 8: Govinda

Siddhartha, now an enlightened soul, encounters his old friend Govinda, who is still a devoted disciple of Buddha. Govinda, though aged, is still seeking spiritual truth. He fails to recognize Siddhartha at first but is drawn to his serene presence and profound wisdom. Siddhartha, transformed by his journey, shares his understanding of life, truth, and the nature of enlightenment.

He explains to Govinda that true wisdom cannot be taught or transferred but must be realized through personal experience. He criticures the limitations of doctrines and intellectual pursuits, emphasizing the importance of direct experience and inner realization. He shares his insights on the interconnectedness of all beings, the ephemeral nature of worldly pursuits, and the ultimate unity of existence.

Siddhartha explains that his journey was one of self-discovery, of shedding societal conditioning and external doctrines to embrace his own innate truth. He speaks of the cyclical nature of life, the interconnectedness of all things, and the ultimate futility of resisting the natural flow of existence. He realizes that true peace and enlightenment come from acceptance, surrender, and the realization of one's true self.

Govinda, initially skeptical, is deeply moved by Siddhartha's profound wisdom and inner peace. He recognizes the transformative power of Siddhartha's journey and the depth of his understanding. In a moment of profound spiritual connection, Govinda embraces Siddhartha, acknowledging his transformation and the path he has forged. Siddhartha's journey culminates in a state of profound peace, wisdom, and self-realization, transcending the limitations of doctrines and external teachings. He has found his true self by embracing the river of existence and its eternal flow.