Sastravartasamucchaya

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Šāstravārtāsamuccaya" by Acarya Haribhadrasuri, translated by K. K. Dixit, based on the provided pages:

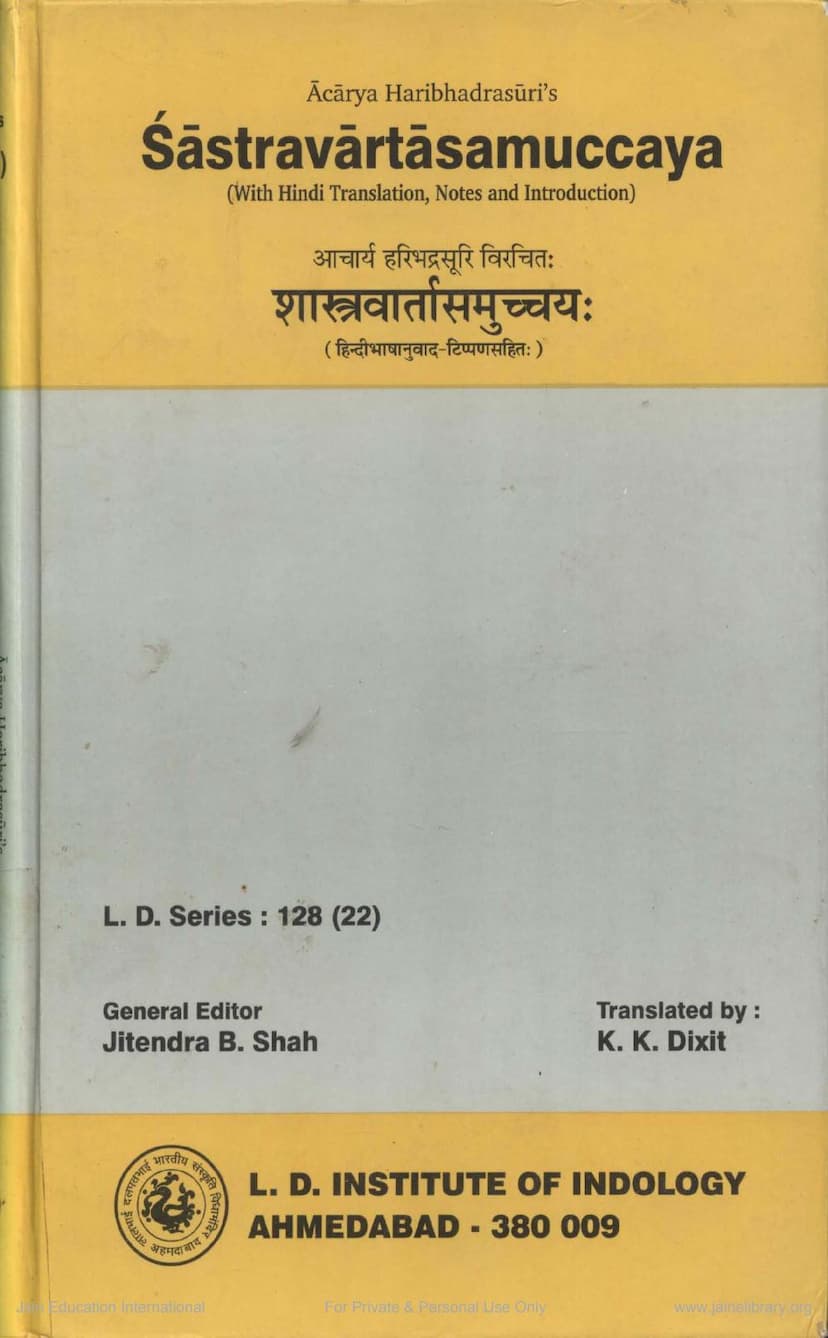

Title: Šāstravārtāsamuccaya (Collection of Discussions on Doctrines) Author: Acārya Haribhadrasūri Translator (Hindi): K. K. Dixit Publisher: L. D. Institute of Indology, Ahmedabad Publication Year: First Edition: 1969, Second Edition: 2002

Overview:

The Šāstravārtāsamuccaya is a significant philosophical work by the broad-minded and prolific Jain monk, Acārya Haribhadrasūri (estimated to be from the 8th-9th century CE). The text engages in a critical examination of the main philosophical problems prevalent in Indian philosophy during Haribhadrasuri's time. Unlike purely destructive criticism, Haribhadrasuri's approach is characterized by constructive critique, reflecting the Jain principle of non-absolutism (syādvāda). He not only explains and analyzes the doctrines of non-Jain schools but also seeks to harmonize them with Jain thought from a particular viewpoint, often by reinterpreting their core tenets. The text is noted for its intellectual rigor, its engagement with a wide range of philosophical schools, and its inclusion of verses borrowed from other scholars, referencing figures like Bṛhaspati, Buddha, Dharmakīrti, Jaimini, Kapila, Manu, and Vyāsa.

Structure and Content:

The work is divided into eleven sections or "stabakas" (chapters), following the organizational principle of Upadhyaya Yashovijayji, who wrote a commentary on this work. The Šāstravārtāsamuccaya addresses fundamental philosophical questions, including:

- The existence of the soul: Haribhadrasuri refutes materialistic views (Bhūtcaitanyavāda), arguing for the soul's existence based on direct self-experience ("I exist"). He also explores differing views on the soul and its relationship with karma.

- Non-violence (Ahiṁsā): This is presented as a fundamental principle, with discussions on what constitutes sin and virtue, and the means to attain liberation.

- Causation: The text examines various theories of causation, including time (Kālavāda), nature (Svabhāvavāda), destiny (Niyativāda), karma (Karmavāda), and the combination of factors (Kālādisāmagrīvāda).

- Idealism vs. Realism: Haribhadrasuri critiques Buddhist theories like momentariness (Kṣaṇikavāda) and idealism (Vijñānadvaitavāda), defending the Jain perspective of the coexistence of permanence and change.

- Omniscience (Sarvajñatā): The text engages with criticisms of omniscience, particularly from the Mīmāṁsā school and some Buddhist thinkers, and defends the concept.

- Permanence and Change (Nityānityatva): The seventh stabaka specifically supports the Jain doctrine of the simultaneous existence of permanence and change in all things.

- Monism vs. Pluralism: Haribhadrasuri critiques monistic theories like Brahma-advaitavada (non-dualism of Brahman) as found in Advaita Vedanta.

- The Nature of Liberation (Mokṣa): The text explores the possibility and means of achieving liberation, emphasizing the role of pure dharma.

- The Relationship between Words and Things (Śabdārthasaṁbandha): The eleventh stabaka delves into the nature of language and its connection to meaning, critiquing the Buddhist view that there is no inherent connection.

Methodology and Philosophical Approach:

Haribhadrasuri's approach is systematic and comprehensive. He dedicates specific sections to critiquing distinct philosophical schools and their doctrines:

- Materialism (Lokayata/Cārvāka): Critiqued in the first and second stabakas for denying the soul and the afterlife.

- Theories of Causality (Kālavāda, Svabhāvavāda, Niyativāda, Karmavāda): Discussed in the second stabaka, highlighting their limitations and proposing a synthesis with karma as a crucial factor.

- Theism (Īśvaravāda - Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika): Critiqued in the third stabaka, questioning the need for an external divine agent when individuals are responsible for their actions.

- Nature-Spirit Dualism (Prakṛti-Puruṣavāda - Sāṁkhya): Critiqued in the third stabaka, particularly regarding the nature of Prakṛti and its relationship to Puruṣa.

- Momentariness (Kṣaṇikavāda - Sautrāntika Buddhism): Extensively refuted in the fourth and sixth stabakas, as it is considered a major philosophical challenge to Jain realism and the concept of continuity.

- Consciousness-Only Idealism (Vijñānadvaitavāda - Yogācāra Buddhism): Critiqued in the fifth stabaka for its denial of external reality and its implications for liberation.

- Emptiness (Śūnyavāda - Madhyamaka Buddhism): Critiqued in the sixth stabaka, questioning the logical consistency of asserting emptiness for all things.

- Monism (Brahmādvaitavāda - Advaita Vedānta): Critiqued in the eighth stabaka, focusing on the logical inconsistencies of positing an absolute non-dual reality and the role of illusion (avidyā).

- Denial of Omniscience (Sarvajñatāpratiṣēdhvāda - Mīmāṁsā and some Buddhists): Critiqued in the tenth stabaka, defending the possibility and reality of omniscience.

- Denial of Word-Meaning Connection (Śabdārthasaṁbandhapratīṣēdhvāda - Sautrāntika Buddhism): Critiqued in the eleventh stabaka, defending the conventional and real connection between words and their meanings.

Key Jain Tenets Supported:

The work fundamentally supports core Jain doctrines, notably:

- Anekāntavāda (Non-absolutism): The principle that reality is multifaceted and can be viewed from multiple perspectives, leading to a constructive and non-confrontational approach to philosophical debate.

- Nityānityatva (Simultaneous Permanence and Change): As elaborated in the seventh stabaka, this is a central Jain ontological principle, asserting that all entities possess both enduring substance (dravya) and transient modifications (paryāya).

- The Efficacy of Karma and the Soul: The existence of the soul and the mechanism of karma are central to understanding bondage and liberation.

- The Importance of Right Faith, Knowledge, and Conduct (Triratna): These are presented as the path to liberation, with a particular emphasis on pure conduct (cāritra) and the culminating states of knowledge (jñāna) and practice.

Translator's Contribution:

Dr. K. K. Dixit's Hindi translation is praised for its lucidity and clarity. He also provides explanatory notes to elucidate difficult verses and clarify the purport of the text. His introductory analysis provides a critical account and estimate of each section, contributing significantly to the understanding of this complex work.

Significance:

The Šāstravārtāsamuccaya is a valuable resource for understanding the landscape of Indian philosophy in the post-classical period. Its Jain perspective, characterized by intellectual humility and a commitment to reconciling differing viewpoints, offers profound insights into the philosophical discussions of its era. The text is highly recommended for students and scholars of Indian philosophy.