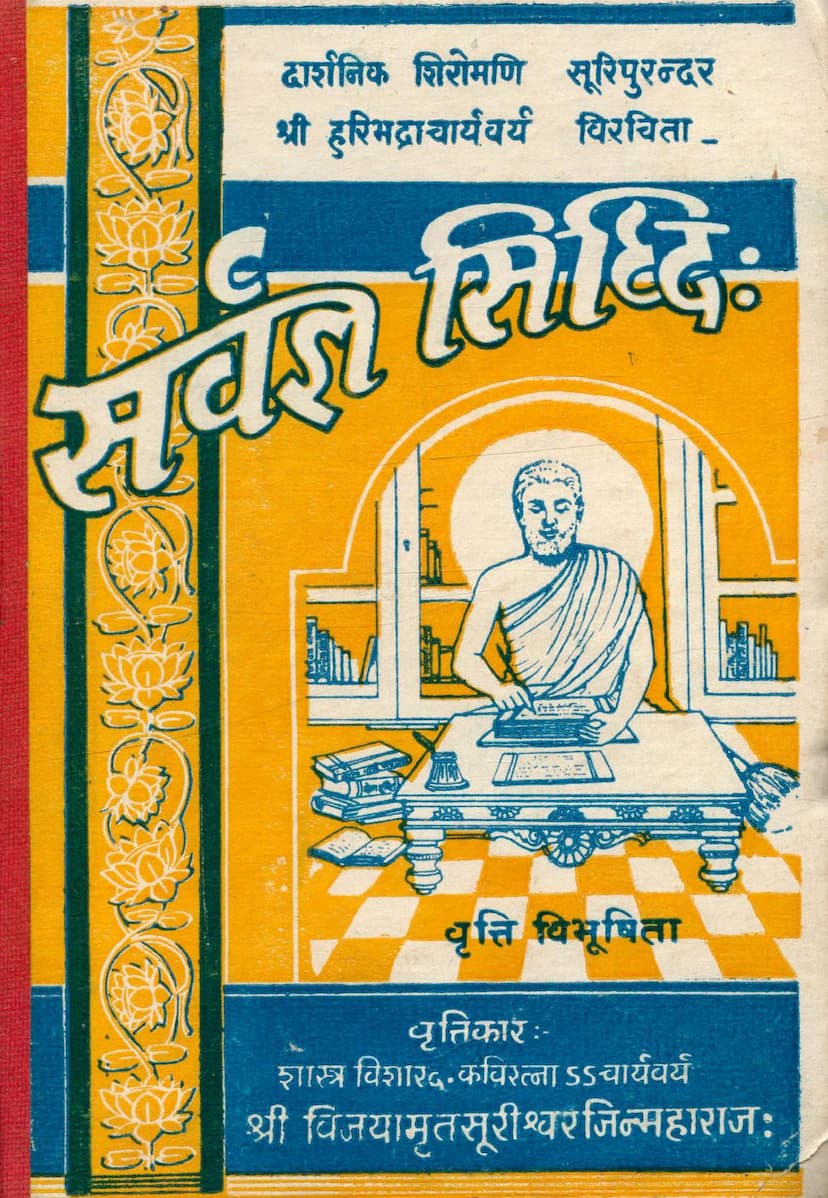

Sarvagna Siddhi

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

The book "Sarvagna Siddhi" (सर्वज्ञ सिद्धि) by Acharya Shri Haribhadrasuri, with a commentary (Vritti) called "Sarvahita" (सर्वहिता) by Acharya Shri Vijayamrutsuri, is a significant Jain philosophical text. Its central aim is to establish the concept of Sarvajñatva (सर्वज्ञत्व), meaning omniscience or the state of knowing everything, in Jainism.

Here's a comprehensive summary based on the provided text:

1. Purpose and Context: The text addresses the philosophical debate surrounding the existence and nature of an omniscient being (Sarvajña), a concept central to Jainism. It aims to refute arguments against omniscience proposed by various philosophical schools and establish the Jain understanding of a Sarvajña. The commentary by Acharya Vijayamrutsuri is designed to make this complex text accessible to a wider audience.

2. The Nature of Sarvajña: The book defines a Sarvajña as someone who possesses:

- Absolute and Unhindered Knowledge: They know all substances, all their states, and all past, present, and future events.

- Freedom from Defects: They are free from the impurities of karma (like ignorance, perception-obscuring, and conduct-obscuring karmas) that limit ordinary beings.

- Unwavering Perception: Their knowledge is direct, immediate, and not dependent on sensory perception or inference.

- Purity and Absence of Attachment/Aversion: They are completely free from passions like attachment (raga), aversion (dvesha), and delusion (maya).

3. Refutation of Opposing Views: The core of "Sarvagna Siddhi" lies in its methodical refutation of arguments that deny or redefine omniscience. The text systematically addresses and counters the claims of various schools of thought:

- Charvakas/Materialists: They deny anything beyond immediate sensory perception and thus reject the existence of an omniscient being who knows beyond the senses. The text argues that relying solely on sensory perception limits understanding and that such a view is materialistic and fails to grasp the true nature of reality.

- Mimamsakas: They often prioritize Vedic injunctions and deny an omniscient creator or revealer, believing in the eternality of Vedas. The text criticizes their complex interpretations of Vedas and their denial of an omniscient being, calling their philosophy a "maya-jaal" (web of illusion).

- Sankhyas and Yoga: While acknowledging an eternal soul, they don't fully embrace a Sarvajña in the Jain sense, often seeing the soul as a passive witness or dependent on Prakriti (nature). The text notes their skepticism or indifference to the concept of omniscience.

- Buddhists: They accept a form of omniscience but often define it as knowing the "essential truth" or "desired meaning" rather than knowing absolutely everything, including minute details. The text critiques this limited view, citing a story where Buddha dismisses a question about the number of insects on a cart as irrelevant, implying a focus on essentials over exhaustive knowledge. The text argues that true omniscience encompasses all.

- Naiyayikas and Vaisheshikas: They believe in an omniscient God as the creator but distinguish this from the Jain concept of a liberated soul (Jiva) becoming omniscient through the destruction of karmic impediments. The text notes that their view of liberation, where the soul becomes devoid of knowledge, is a point of contention and ridicule.

- Vedantins: They assert the oneness of Brahman and the universe, with Brahman being the ultimate omniscient reality. However, they often consider the material world and individual souls as Maya (illusion), and their concept of an omniscient being is different from the Jain view of an omniscient liberated soul.

4. Arguments for Sarvajña: The book employs various Pramanas (means of valid knowledge) to establish the existence of a Sarvajña:

- Direct Perception (Pratyaksha): The text argues that while sensory perception is limited, the very concept of knowledge and its validity implies a source that can provide such comprehensive understanding. It also asserts that the existence of Sarvajña is established through the testimonies of those who have attained perfect knowledge (like Tirthankaras).

- Inference (Anumana): The text presents logical arguments, often in the form of syllogisms, to infer the existence of a Sarvajña. It addresses common objections to inference, such as the problem of the unknown (viparyaya) and the unperceived (aviparīta). A key argument is that the very act of knowing and discerning is limited by the knower's inherent capacity, and to have complete knowledge, an omniscient being is necessary.

- Testimony (Shabda/Agama): Jain scriptures, considered to be the words of omniscient beings (Tirthankaras), are presented as a primary source of evidence. The text argues that if we accept the validity of scriptures for matters beyond our immediate perception (like heaven or the efficacy of rituals), then we must accept the authority of the omniscient revealer of these scriptures. The text engages with arguments that question the validity of scripture due to its potential human authorship, countering that scriptures are the infallible teachings of Tirthankaras, not mere human pronouncements.

- Analogy (Upamana): Analogies are used to explain the concept and its perceivability, even if indirectly. For instance, the analogy of knowing a yak (gavaya) by its resemblance to a cow is used to illustrate how understanding the characteristics of an omniscient being can be approached.

- Postulation (Arthapatti): This involves inferring a cause to explain a known effect. The text uses arguments like the existence of scriptures describing heaven and liberation, which implies a source capable of knowing these realities.

5. Key Philosophical Concepts Discussed:

- Pramanas: The text delves into the nuances of each valid means of knowledge (Pratyaksha, Anumana, Shabda, Upamana, Arthapatti, and sometimes Anupalabdhi) and how they apply or are misused in arguments against Sarvajña.

- The Nature of Knowledge: The book distinguishes between limited knowledge (pratyaksha, anumana etc.) and the absolute, direct, and all-encompassing knowledge of a Sarvajña.

- The Problem of Defects: It addresses how passions like attachment and aversion, and karmic impediments, limit the knowledge of ordinary beings, and how these are absent in a Sarvajña.

- Syadvada (Anekantavada): The Jain principle of manifold perspectives is implicitly present, as the text engages with and refutes various philosophical standpoints. It emphasizes that a complete understanding of reality, including the concept of omniscience, requires embracing the complexities that exclusive or one-sided views (ekanta vada) fail to capture.

6. Structure and Commentary: The book, "Sarvagna Siddhi," presents its arguments in a logical, debate-like format, often posing objections (purvapaksha) and then refuting them (uttarapaksha/siddhanta). The commentary, "Sarvahita," by Acharya Vijayamrutsuri, is crucial for clarifying the intricate arguments and technical philosophical terminology, making the original text understandable.

In essence, "Sarvagna Siddhi" is a rigorous defense of the Jain doctrine of omniscience, employing sophisticated philosophical reasoning and scriptural evidence to establish the existence and nature of the omniscient Tirthankaras and their teachings. It aims to demonstrate that true liberation and comprehensive understanding are only possible through the path illuminated by an omniscient being.