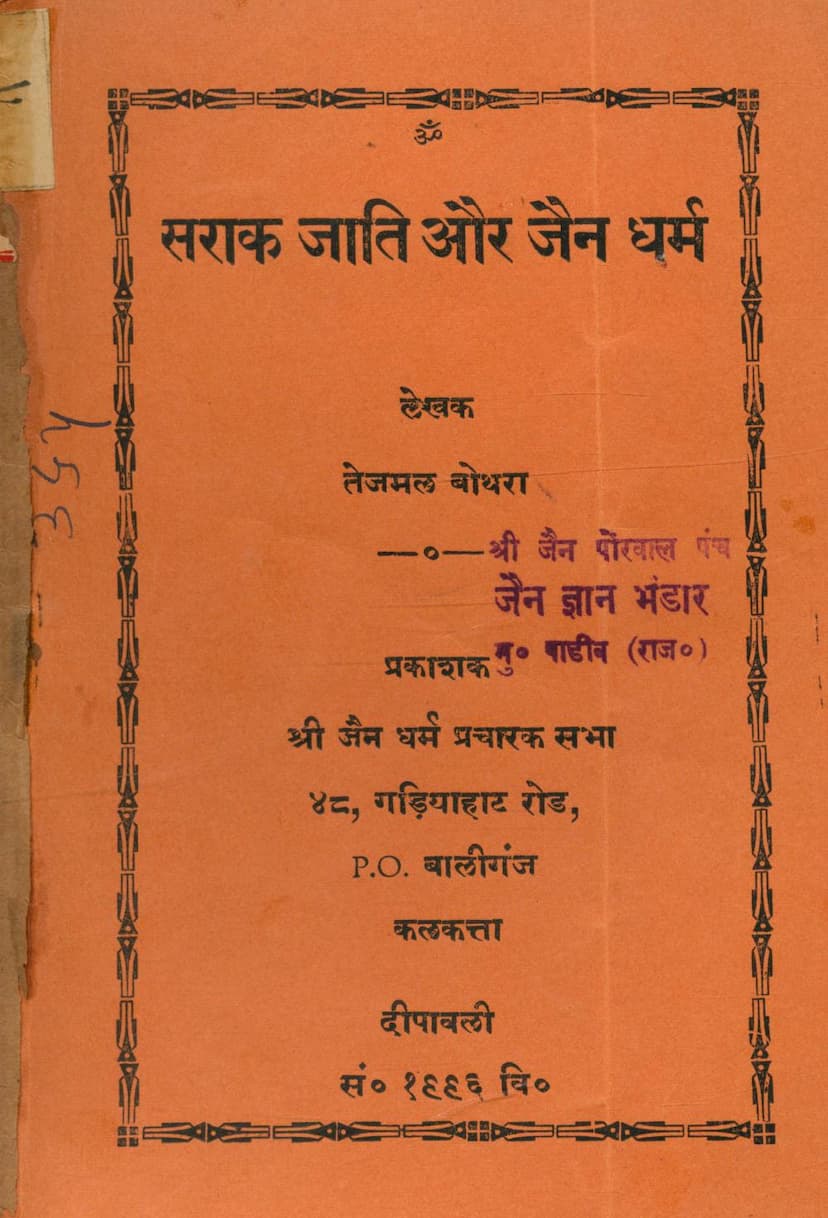

Sarak Jati Aur Jain Dharm

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Sarak Jati Aur Jain Dharm" (The Sarak Community and Jain Dharma) by Tejmal Bothra, based on the provided pages:

This book, published by Shri Jain Dharm Pracharak Sabha, aims to highlight the significant and often forgotten connection between the Sarak community residing in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, and the Jain Dharma. The author expresses immense joy in discovering that this community, despite having lost touch with their original identity, are, in fact, Jain Shravaks.

Key Arguments and Evidence Presented:

- Origin and Identity: The book asserts that the Sarak community are descendants of ancient Jains who settled in regions like Manbhum, Singhbhum, Purulia, Ranchi, Rajshahi, Bankura, and Midnapur, as well as parts of Orissa, even before the arrival of the Bhumij people. Their traditions, customs, and even their names suggest a strong Jain lineage.

- Evidence from Government Reports and Gazettes: The author heavily relies on government publications like Census Reports and District Gazettes to support his claims.

- Manbhum Gazetteer (1911): Pages 51 and 83 are cited, stating that the Sarak people are "obviously Jains by origin." Their traditions and those of their neighbors indicate they are descendants of a race present before the Bhumij, credited with building temples at places like Para, Chharra, and Bhoram. They are described as a peaceable race.

- Puri Gazetteer (1908): This report explains that the word "Sarak" is likely derived from the Sanskrit word "Shravak," meaning "listener" or a lay follower of Jainism. Historically, it distinguished lay followers from monks. The report notes that some Saraks took to weaving and are known as "Saraki tanti." It also mentions their annual assembly at the Khandagiri caves to pay homage to Jain idols, which the Saraks themselves acknowledge.

- Bengal Census Report (No. 457, page 206): This report states that in ancient times, Jain settlements were prevalent near Parshvanatha hills, with Manbhum and Singhbhum being key areas. Local lore suggests Saraks ruled these regions and built many Jin temples. Ancient Jain relics and copper mines in Singhbhum are also mentioned.

- Specific Jain Practices and Beliefs:

- Strict Vegetarianism: The Saraks are described as staunch vegetarians, abstaining even from certain fruits like "jamikanda." A saying is quoted: "Doh dumur poḍa chhati, yeh nahin khay Sarak jati" (meaning Saraks do not eat these specific items), highlighting their adherence to specific dietary restrictions not commonly found in other communities.

- Aversion to Night Meals: Many Saraks consider eating at night to be wrong and some even refrain from it.

- Respect for Jain Idols: While they may not fully understand their religious practices, they worship idols, often recognizing them as forms of Lord Parshvanatha. The Puri Saraks' annual pilgrimage to Khandagiri caves to worship the idols and sing devotional songs to Lord Parshvanatha is a significant piece of evidence. The devotional song itself is included in the text, praising the divine form of Lord Parshvanatha and contrasting his worship with that of other gods that increase worldly attachments, leading to liberation.

- Gotras: Their gotras, such as Adidev, Anantdev, Dharmadev, and Kashyap, are identified with the gotras of Jain Tirthankaras like Lord Parshvanatha and Lord Mahavir Swami, which is considered highly improbable for non-Jain communities.

- Presence of Jain Idols: Jain idols are still found in some of their villages and homes, and they venerate them.

- Inscriptions: A stone inscription in the Beloja (Katrasgarh) Jain temples mentions "Chichitagar aur Shravaki Raksha Vanshipara," indicating that these temples remained under the care of the descendants of Shravaks.

- Reasons for Identity Loss: The book acknowledges that due to centuries of living in environments disconnected from Jainism, in societies with a prevalence of violence and a lack of spiritual discourse, the Saraks have gradually forgotten their true identity. They sometimes identify themselves as Buddhists or Hindus, and some even consider themselves Shudras.

- Call to Action for the Jain Community: The author expresses concern over the current state of indifference within the Jain community towards reclaiming these lost brethren. He emphasizes the urgent need for the Jain society to awaken and take action to reintroduce the Saraks to their ancestral faith. He points out that this is a golden opportunity to increase the Jain population and prevent further assimilation.

- Efforts Underway: The book highlights that several prominent individuals, including Babu Bahadur Singhji Singhi and Ganeshlalji Nahata, have drawn attention to this cause. Under their inspiration, respected Jain scholars like Upadhyay Shrimangalvijayji Maharaj and his disciple Shrimad Prabhakar Vijayji Maharaj are actively engaged in religious propagation among the Saraks. Organizations like "Shri Jain Dharm Pracharak Sabha" in Calcutta and Jharia have been established to support this work and have achieved considerable success.

- Appeal for Support: The author implores the Jain community, including monks and followers, to contribute their time, mind, and wealth to this noble cause. He stresses that it is a great shame if they cannot help these receptive brothers who wish to be embraced by their Jain family. This endeavor is seen as a paramount duty and a significant service to the Jain faith, promising immense spiritual merit and eternal fame.

In essence, "Sarak Jati Aur Jain Dharm" is a compelling call to awareness and action, presenting strong evidence that the Sarak community are lost Jain Shravaks and urging the modern Jain community to reconnect them with their rich heritage.