Sanshay Timir Pradip

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Sanshay Timir Pradip" by Udaylal Kasliwal:

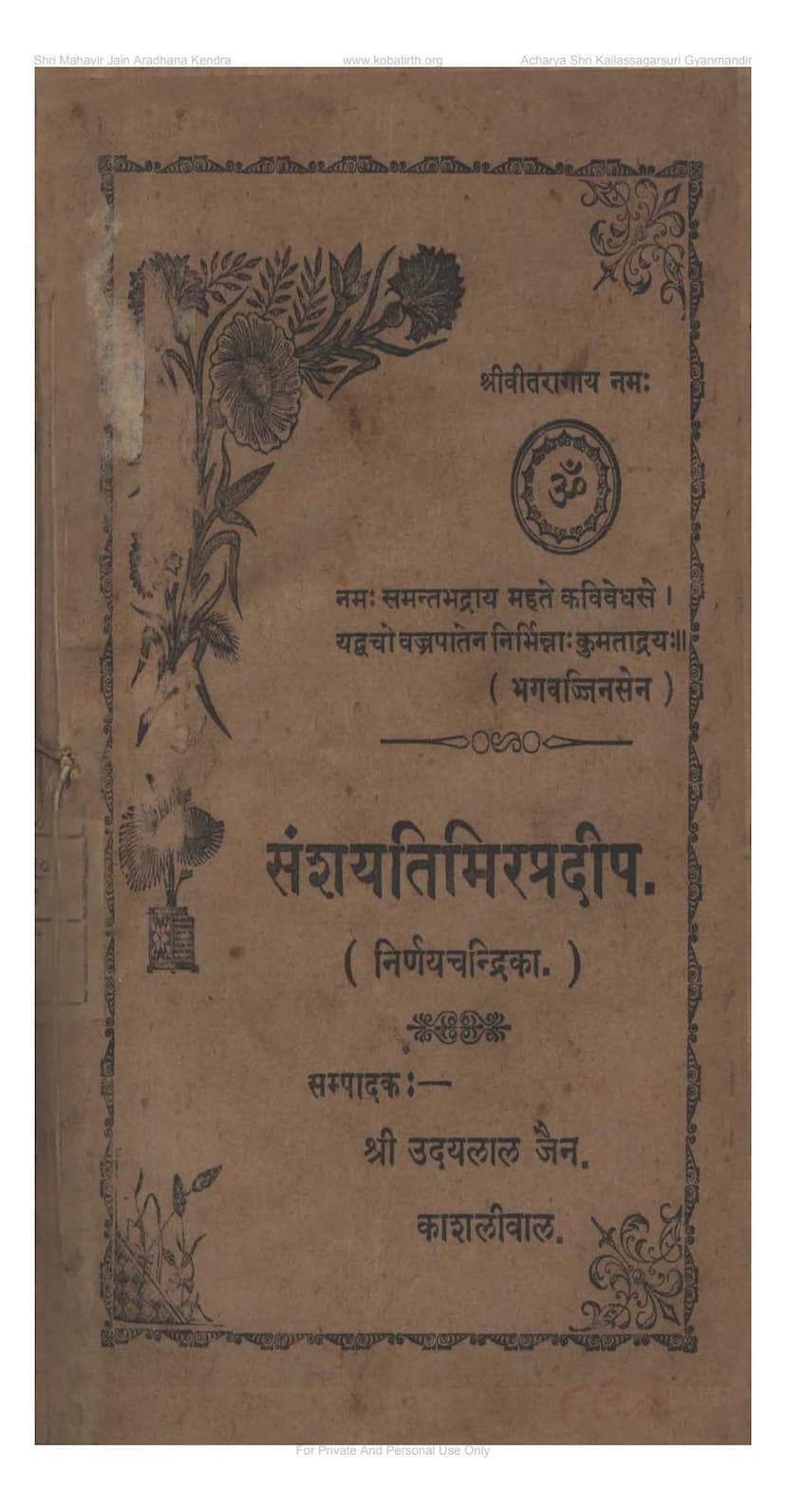

Book Title: Sanshay Timir Pradip (संशय तिमिर प्रदीप) Subtitle: Nirnayachandrika (निर्णयचन्द्रिका) Author: Udaylal Jain Kasliwal Publisher: Swantroday Karyalay Publication Year: Second Edition (द्वितीय वृत्ति) - 1909 CE (Veer Nirvana 2435)

Overall Purpose and Theme:

"Sanshay Timir Pradip," which translates to "Lamp for the Darkness of Doubt," is a foundational work in Jain literature aiming to clarify and resolve doubts prevalent among the Jain community regarding various religious practices and principles. The author, Udaylal Kasliwal, addresses these doubts with a commitment to impartiality and a deep reverence for the teachings of ancient Jain ascetics and scriptures. The book seeks to guide individuals towards the true understanding and practice of Jainism by dispelling misconceptions and presenting scriptural evidence.

Key Content Areas and Arguments:

The book is structured as a series of essays and answers to questions, systematically addressing various aspects of Jain ritual, philosophy, and practice. The core of the author's approach is to rely on ancient Jain scriptures and the interpretations of respected acharyas to validate or refute common beliefs and practices. The author emphasizes the importance of scripture-based reasoning over personal opinions or trends.

Summary of Major Topics Discussed (Based on the Table of Contents and Key Sections):

-

Manglacharan (Invocation): The book begins with traditional invocations to the Jin Tirthankaras, seeking blessings for the endeavor.

-

Uddesh of Maharisheesh (Purpose of Great Sages): The author outlines the objective of the great sages in guiding householders, emphasizing the shift from outward practices to inner purification and the practical challenges faced by householders in their daily lives.

-

Panchamritabhishek (Five Nectars Ablution): A significant portion of the book is dedicated to defending the practice of Panchamritabhishek. The author addresses criticisms that this practice might lead to the creation of life due to the sweet substances used (like sugarcane juice, milk, ghee, curd, honey). He argues that this is permissible according to numerous ancient scriptures, citing authors like Umaswami, Vasunandi, Yogindra Dev, Somdev, Indranandi, and Kundakunda. He clarifies that the intent is not to create life but to honor the purity of the divine by offering pure substances and that any residual stickiness is removed by subsequent water ablutions. He dismisses arguments based on Tirthankaras not performing Abhishek in Samavsaran, stating that this does not invalidate idol worship. He also argues that the attachment associated with such practices is not inherently wrong for householders, just as building temples or organizing processions are not.

-

Gandhalepana (Applying Sandalwood Paste/Fragrant Pastes): This section defends the practice of applying fragrant pastes and sandalwood to the idols. The author counters the view that this defiles the idol or reduces its purity, citing numerous scriptural references that mandate or describe this practice. He argues that the intention behind the practice is devotion and that the purity of the idol is maintained through scriptural injunctions, not solely by the absence of external substances. He criticizes the notion that applying fragrance makes an idol less pure, comparing it to the purification of certain natural substances like kasturi (musk) or camphor. He also addresses the argument that if external adornments are avoided to maintain the "nirgrantha" (unclothed) nature of the Jin images, then other practices like using umbrellas or fans should also be avoided.

-

Pushpa Pujan (Flower Worship): The author discusses the practice of offering flowers to the idols. He clarifies that while fresh flowers are preferred, the use of rice grains dyed with saffron (as a substitute for flowers when fresh ones are unavailable) is also supported by scriptures. He addresses the criticism of violence (himsa) associated with using flowers, stating that the intention and outcome (purified state of mind) matter more. He provides scriptural evidence for flower offerings from various texts and explains the rewards of such devotion.

-

Pushpa Kalpana (Imagined Flowers): This section likely discusses the permissible methods of creating substitute flowers when fresh ones are unavailable, such as using dyed rice grains. The author validates this practice based on scriptural references, emphasizing the principle of adhering to the spirit of the injunction when the literal practice is not possible.

-

Kalash Karini Chaturdashi (Water Pot Ritual on Chaturdashi): The author discusses rituals performed on a specific Chaturdashi (14th lunar day). He addresses the practice of offering water pots or discarded flower garlands. He defends the latter as a scripturally supported practice, arguing that it is not an act of theft (mushitdravya) when done according to scriptural guidelines and that it is a way to receive the blessings of the divine.

-

Sanmukh Pujan (Worship Facing Forward): This section likely deals with the direction and posture of the worshipper during rituals. The author emphasizes the importance of worshipping facing forward (towards the idol) and following scriptural guidance regarding the direction of the worshipper and the idol. He contrasts this with practices in Samavsaran, explaining that the context of idol worship in temples differs from the divine presence in Samavsaran.

-

Baithi Pujan (Sitting Worship): The author discusses the practice of performing worship while sitting. He validates this practice by citing scriptures that describe devotees sitting while performing rituals. He argues against the notion that standing is inherently more respectful, citing examples of honored guests being offered seats.

-

Shraddha Nirnaya (Decision on Shraddha): The author clarifies the Jain understanding of "Shraddha" (devotion, faith), distinguishing it from the Brahmanical ritual of the same name (offering to ancestors). He defines Jain Shraddha as sincere and devoted giving or offering, aligning it with the practice of Dana (charity) as a core aspect of Jain householder life. He criticizes those who condemn the term "Shraddha" due to its association with other religions without understanding its Jain context.

-

Achaman and Tarpan (Ritual of sipping water and offering water): This section addresses practices like Achaman (sipping water) and Tarpan (offering water), often associated with Brahmanical rituals. The author argues that these practices, when performed for purification and as part of Jain worship (e.g., before puja), are permissible and have scriptural basis within Jain texts, even if the terms themselves are also used in other traditions. He emphasizes the importance of outer purity for inner spiritual practice.

-

Gomaya Shuddhi (Purification with Cow Dung): The author defends the traditional Jain practice of using cow dung for purification of spaces, especially for kitchens and ritual areas. He counters the argument that cow dung is inherently impure, citing scriptural references and explaining that in Jain tradition, it is considered purifying. He also addresses the use of cow dung in rituals like Niranjan (Aarti) and its scriptural backing.

-

Dana Vishaya (Topic of Charity - Dashdan): This extensive section discusses various types of charity (Dashdan) recommended in Jain scriptures, including giving land, gold, daughters (in marriage), elephants, horses, chariots, jewels, cattle, food, and clothing. The author defends these practices, including symbolic 'giving of daughters' as marriage arrangements, and argues that they are prescribed for the well-being and support of the community and dharma, not as mere material transactions. He emphasizes that these donations are made with proper intent and to deserving recipients.

-

Siddhanta Adhyayan (Study of Siddhanta Texts): The author addresses the question of whether householders should study profound Siddhanta texts. He concludes that while monks are the primary audience for these complex texts, householders may study them selectively or with guidance, as the ultimate goal of all Jain practices is spiritual upliftment. However, he notes that the emphasis for householders should be on prescribed duties like charity and worship.

-

Mundana Vishaya (Chaulkarma/Tonsure): The author defends the practice of tonsuring (Shaving the head) for infants as a scripturally supported ritual in Jainism, often performed around the third year of age. He cites scriptures from Mahapurana and Indranandi, among others, detailing the procedures and significance of this rite, including its role in spiritual progress and societal integration. He distinguishes the Jain practice from Brahmanical rituals.

-

Ratri Pujan (Night Worship): The author discusses the practice of worship at night, particularly on specific auspicious days or festivals. He defends this practice as a legitimate "naimittik" (occasional) ritual, supported by scriptural accounts of night worship during certain festivals. He addresses concerns about increased "arambha" (activity/effort) and "ayatanachar" (lack of carefulness) during the night, arguing that these are matters of individual diligence rather than an inherent flaw in night worship itself. He notes that some rituals, like evening prayers or specific festival observances, naturally occur at night or dusk.

-

Shasan Devata (Guardian Deities of the Faith): This is a significant and nuanced discussion. The author defends the practice of venerating "Shasan Devatas" (deities protecting the Jain faith) as scripturally sanctioned. He argues that these deities, while not the ultimate object of worship (Jinas), play a role in protecting the dharma and assisting those who uphold it. He distinguishes them from "Kudevata" (false deities) and argues that showing them respect is not "mūḍhatva" (delusion) but a way of honoring the protectors of the faith. He draws parallels to honoring other respected individuals or entities. He cites scriptures that mention specific Shasan Devatas and their roles. He addresses the interpretation of certain verses by Samantabhadra which seem to condemn venerating other deities, clarifying that these verses likely refer to non-Jain deities or those worshipped with worldly desires.

Author's Tone and Approach:

- Impartiality and Scholarly Rigor: Throughout the book, Kasliwal emphasizes his commitment to impartiality and fairness. He urges readers to approach the text with an open mind, considering the scriptural evidence rather than adhering to preconceived notions.

- Respect for Tradition: The author consistently refers to and quotes ancient Jain scriptures and the pronouncements of renowned acharyas to support his arguments.

- Addressing Doubts: The primary purpose is to remove confusion and doubt ("Sanshay Timir") from the minds of the readers, providing clarity based on authoritative sources.

- Critique of Modern Trends: While respectful of established practices, the author also subtly critiques certain deviations from scriptural norms that have emerged in contemporary Jain society, often due to ignorance or misinterpretation.

- Emphasizing the Householder's Path: Many sections highlight the specific duties and spiritual practices suitable for householders, acknowledging the practical constraints they face.

Significance:

"Sanshay Timir Pradip" is a valuable resource for understanding and practicing Jainism, particularly for lay followers. It serves as a comprehensive guide to many common rituals and philosophical points, offering a scripturally grounded perspective that aims to resolve uncertainties and foster a deeper, more accurate understanding of Jain principles. The book's strength lies in its extensive use of quotations from authoritative Jain texts, providing a robust defense of various traditional practices.