Samadhanni Anjali

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Samadhanni Anjali," based on the provided pages:

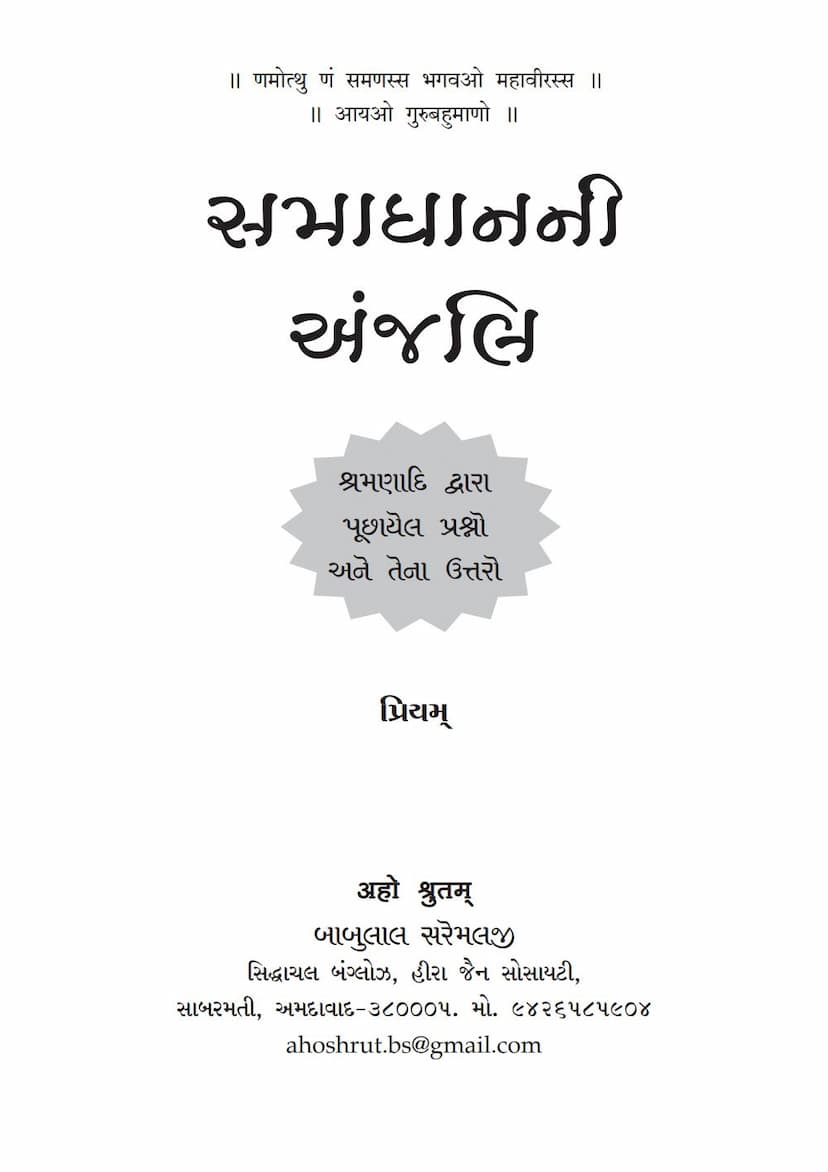

Book Title: Samadhanni Anjali (A Salutation of Resolution) Author: Priyam Publisher: Ashapuran Parshwanath Jain Gyanbhandar

This book is a collection of questions posed by ascetics (Shramanas) and their answers provided by the author, Priyam. The text delves into various practical and theoretical aspects of Jainism, focusing on ascetic conduct, ethical considerations, and philosophical interpretations.

Key Themes and Discussions:

The book addresses a wide range of inquiries, offering detailed explanations rooted in Jain scriptures and traditions. Some of the prominent themes include:

-

Food and Ascetic Observances (Aneshanā):

- Refrigeration and Offering: The text clarifies that keeping food (like mango pulp or rotis) outside the fridge for potential offerings, even if not certain, doesn't incur sthāpanā doṣa (fault of establishing forbidden items) if the intention is for potential offerings. However, if a portion is kept for self and another for offering, it constitutes sthāpanā doṣa. The author explains that the fridge itself is a source of teu-kāya (living beings of heat-body) and ap-kāya (living beings of water-body) that can lead to anēshanā (faulty acquisition of food). Avoiding the fridge is not seen as a fault.

- Intention in Preparation: The intent behind preparing food is crucial. If rotis are made with the primary intention of offering, even if not explicitly designated, it's understood. However, if the intention is for general use and the possibility of offering arises, it's viewed differently.

- Pūti Doṣa (Spoilage Fault): The discussion explores whether pūti doṣa originates solely from householders or can also apply to ascetics. It's explained that while the initial fault might be human-generated, the ascetic's failure to properly purify utensils (tri-kalpa) can also lead to pūti doṣa. The author clarifies that such faults are indirectly linked to householders.

- Water and Āyambil: The use of "ādhākarma" (food prepared with impure water) water for purification (tri-kalpa) is discussed, stating that it might still result in pūti doṣa. However, such faults are considered aśakya-parihāra (unavoidable) and thus excusable, but the practice of purification should continue to maintain reverence.

- Āyambil with Faulty Water: If one observes āyambil with ādhākarma water, it's considered a fault. The ideal scenario is using pure water. If unavoidable, the practice should be done with introspection, focusing on purity in other aspects of consumption.

- Dal Sthāpanā: Establishing dal (lentils) is discussed, noting that it often involves ādhākarma faults, making it difficult to find completely pure dal.

-

Types of False Beliefs (Mithyātvā):

- Believing the Deceased Alive: The text addresses whether believing a deceased person (like Baldev regarding Vasudev) to be alive constitutes mithyātvā. It's explained that if the belief is due to attachment or sentiment rather than a fundamental misperception of reality (e.g., denying what the omniscient has declared as non-living), it might not be considered outright mithyātvā, though excessive attachment could lead to deviations.

-

Ascetic Terminology and Concepts:

- Devapiṇḍa: This refers to food offered by deities. The text cites examples from scriptures where deities offer food to ascetics.

- Abhiniveśik Mithyātvā: This type of false belief is characterized by obstinate adherence to wrong doctrines (kadāgraha), even when presented with correct teachings.

- Matijñāna vs. Cakṣu/Acakṣu Darśana: The distinction between knowledge gained through the senses (matijñāna) and direct perception (darśana) is clarified. While matijñāna provides a general understanding, the perception through darśana is more direct and specialized.

- Darśanāvaraṇīya vs. Āśātā Vedanīya: The text explains that darśanāvaraṇīya karma obstructs perception, while āśātā vedanīya karma causes suffering.

- Darapāla vs. Khajānchi: The analogy of a gatekeeper (pratihārī) obstructing royal access for darśanāvaraṇīya karma and a treasurer (khajānchi) obstructing wealth for antarāya karma is used to explain their difference.

-

Karma and Lifespan:

- Increasing Lifespan: The book states that lifespan cannot be increased even by a moment. While certain bodily functions like breathing are used as time measures, they have no direct correlation with increasing lifespan.

- Antarāya Karma: This karma obstructs fruition and is classified as ghāti (destructive) because it hinders the soul's innate potential and auspicious states of being.

-

Body and Physical Forms:

- Vaikriya and Āhārak Bodies: The text discusses the creation of different bodies, explaining that when a vaikriya body is formed, it's separate from the original body.

- Devas' Transformations: Devas can transform into various forms (like snakes, scorpions, elephants). The text clarifies whether these forms are animate or inanimate, stating that transformations are linked to the self's soul-matter. Even inanimate transformations can exhibit movement through divine power.

-

Spiritual Practices and Conduct:

- Bahubali's Doubt: The doubt of Bahubali regarding bowing to his younger brothers is analyzed. It's suggested that he knew the rules but perhaps felt a sense of personal distinction ('aham') or that the customs of the time required it.

- Vandana vs. Kritkarma: The text differentiates between "vandana" (salutation, often involving folding hands) and "kritkarma" (ritualistic actions), noting that even after attaining omniscience, certain outward salutations might cease.

- Lord Mahavir's Incarnation: The reasons behind Indra not personally performing Lord Mahavir's conception and transfer are discussed, suggesting considerations like honor, sacred customs, and the roles of subordinate deities.

- Prarthanā Sūtra: The intention behind prayer formulas is to achieve higher spiritual states and attain them in every rebirth until liberation.

- Laṁghana: This refers to the eternal identifying marks of Tirthankaras.

- Tirthankara's Dana (Charity): The text discusses the fixed amount of charity given by Tirthankaras, attributing it to the absence of beggars and the established customs of giving. It also mentions that the charity wasn't limited to gold coins but included other valuable items.

-

Cosmology and Geography:

- Antardvipa (Inner Islands): The book explains the placement and nature of inner islands, clarifying that their designation as "islands" is based on specific cosmological descriptions and may not align with everyday understanding of land surrounded by water.

-

Vows and Abstinence (Virati and Avirata):

- Sin of Non-Abstinence: The concept that even without performing a sin, the lack of taking a vow of abstinence (avirati) leads to sin is discussed. It's clarified that for a fully ascetic (sarvavirata), this principle of avirati doesn't apply in the same way as for householders. The vows of ascetics encompass the renunciation of all sinful activities.

- Value Limits on Possessions: The text explains that for ascetics, there are implicit renouncements of possessions above certain value limits, and breaking these incurs penance.

-

Rituals and Traditions:

- Sūtak (Ritual Purity): The concept of sūtak (periods of ritual impurity due to birth or death) is discussed. It's stated that sūtak involves avoiding houses that are considered impure or objectionable in the context of receiving alms. The practice is to avoid taking alms from such houses for a specified period.

- Ādrā Nakṣatra and Auspiciousness: The text mentions that during Ādrā Nakṣatra, specific times are considered inauspicious for study due to the influence of negative deities, as observed by the omniscient.

-

Charity and Service:

- Blood Donation: The practice of blood donation by Jain householders is discussed. The text highlights potential negative consequences, such as the misuse of donated organs and the recipient being irreligious, which could lead to negative karmic outcomes. While not explicitly forbidden, the text advises caution and suggests that such acts may not always align with the core principles of Jain ethics, especially when the recipient's disposition is unknown. The analogy of not lending tools that could be misused is drawn. It also mentions that some donations, while publicized as acts of service, may not always reach the intended recipients.

-

Scriptural Interpretation:

- Understanding Commentaries: The importance of studying commentaries (ṭīkā) is emphasized. While memorizing verses is helpful, understanding the meaning of the words is sufficient for initial comprehension.

- Scripture Authorship: The text addresses the origin of the Mahajinānu Sūtra, suggesting that the presence of terms like "puñjayalihana" does not necessarily imply it was composed after the Vallabhi recension, as texts existed prior to that. The general principle is that unassigned parts of the Āvashyak Sūtras are considered composed by the Ganadharas.

- Lord Mahavir's Penances: The text explains the use of the term "keshalochana" (hair plucking) in commentaries regarding Lord Mahavir's penances, clarifying that it refers to the absence of hair growth rather than the complete absence of hair, which would render certain descriptions contradictory.

In essence, "Samadhanni Anjali" serves as a guide for spiritual aspirants, offering clarity on complex Jain doctrines and practices through a Q&A format. It encourages introspection, adherence to scriptural principles, and a deep understanding of the subtle nuances of asceticism and ethical conduct.