Rup Jo Badla Nahi Jata

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Rup Jo Badla Nahi Jata" (The Form That Does Not Change), based on the provided pages:

Book Title: Rup Jo Badla Nahi Jata (The Form That Does Not Change) Author: Moolchand Jain Publisher: Acharya Dharmshrut Granthmala

Core Theme: The book tells the story of Brahmagulal, a highly talented and popular "Baharupia" (a performer who can transform into various characters) whose profound skill in embodying roles leads him to a spiritual realization and ultimately to renunciation. The central message revolves around the idea of achieving an unchangeable, true self, contrasted with the ephemeral nature of outward appearances and worldly pursuits.

Story Summary:

The narrative begins by introducing Brahmagulal, a charming, intelligent, and well-rounded individual. He excelled in his studies, was knowledgeable in astrology and literature, and also gained spiritual understanding. He was married and lived a life of comfort and freedom, supported by his family and enjoying the king's favor.

Brahmagulal's life took a turn when he developed a passion for becoming a "Baharupia" (a performer who changes his appearance and character). His friend, Mathuramal, supported his interest. Brahmagulal's talent was extraordinary; he could transform into characters so convincingly that people believed they were seeing the actual person. He depicted characters like Ardhanarishvara and Draupadi with such realism that the audience was awestruck. His portrayal of Sita accompanying Rama and Lakshman to the forest was equally praised for its authenticity and demonstration of devotion.

While Brahmagulal received immense praise, wealth, and fame, his parents were concerned. They considered his profession inappropriate for a respectable family, even though they enjoyed his success. His father eventually expressed his disapproval, but Brahmagulal felt compelled to continue, stating it was ingrained in him and brought him contentment.

The king's minister, however, grew jealous of Brahmagulal's popularity, especially as the king himself was so impressed. The minister devised a plan to discredit Brahmagulal. He suggested to the prince that Brahmagulal be asked to transform into a lion. The minister believed that if Brahmagulal couldn't truly embody the ferocity and nature of a lion, his reputation would be ruined.

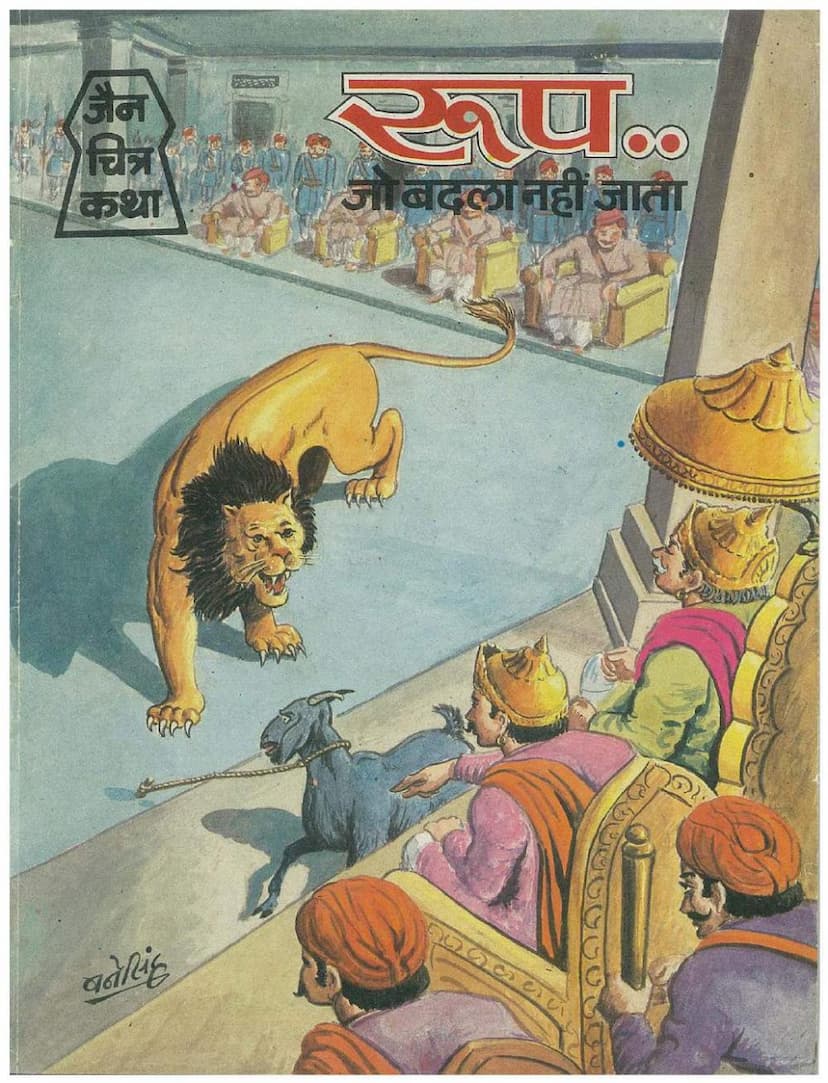

Brahmagulal, accepting the prince's wish, requested an assurance of forgiveness for any transgression he might commit while in the lion's form. The king granted this, even writing a promise of one "blood drop" forgiveness. The next day, in the royal court, Brahmagulal transformed into a fearsome lion. A goat was brought before him. The lion, torn between his artistic commitment and his Jain principles, hesitated. If he killed the goat, he would be committing violence, which went against his faith. If he didn't, his art would be questioned.

The prince, to provoke him, threw a pebble and taunted him, questioning his lionhood. Enraged and losing his composure, Brahmagulal lunged at the prince and fatally attacked him. This act plunged the court into shock and grief. The king was devastated.

The minister then suggested another test: Brahmagulal should take the form of a Digambar Muni (an unclothed ascetic) and offer solace to the grieving king. Brahmagulal agreed, but requested six months' time to prepare. This moment became his opportunity for true transformation. He realized that the form of a Muni was one that, once adopted, could not be changed. He decided to embrace this ultimate form for his own spiritual liberation, seeing it as a culmination of his immense potential.

Brahmagulal informed his family of his decision. His parents and wife were initially worried about the king's reaction and the potential punishment. However, when he explained that becoming a Muni meant he could never return to his former life, his wife was particularly distressed, fearing widowhood. His parents, though hesitant, eventually agreed, perhaps hoping he would return.

Brahmagulal proceeded to the temple, where he took Jain diksha (initiation) as a Digambar Muni in front of the idol of Lord Jinendra. He renounced his worldly possessions, including his hair, and set off into the forest with his picchi (a broom for cleaning the path) and kandalu (a water pot).

Six months later, Muni Brahmagulal returned to the royal court. The king, still grieving, sought his guidance. The Muni preached about the impermanence of life, the illusory nature of worldly relationships, and the importance of detachment and self-realization. He advised the king to engage in spiritual practices for his own well-being. The king, deeply moved, offered Brahmagulal anything he wished, but the Muni asked for nothing and returned to the forest.

Meanwhile, Brahmagulal's family, unable to cope with his absence, went to the forest to bring him back. His father pleaded with him, his mother cried about his youth and lack of grandchildren, and his wife lamented his departure and her perceived widowhood. Brahmagulal, however, remained steadfast in his resolve. He explained that the path of a Muni was one of irreversible commitment and that he was pursuing his true home, Moksha (liberation). He offered his wife the example of seeking refuge in herself and warned her about the limitations of the female form. He then instructed his father to seek out Mathuramal's wife, believing she might be able to convince Mathuramal to join him.

Mathuramal's wife approached her husband, who was urged to go and understand Brahmagulal's decision. Mathuramal found Brahmagulal, who spoke about the suffering caused by worldly attachments. Mathuramal questioned why Brahmagulal was abandoning worldly pleasures when he could have pursued spiritual goals within a householder life through vows. Brahmagulal countered that true peace and liberation were only attainable through the Digambar (unclothed) path.

Mathuramal, contemplating Brahmagulal's words and the realization of the impermanence of worldly life, decided to follow him. He requested the initiation of a Kshullaka (a lesser ascetic) and began living with Muni Brahmagulal.

The story concludes by highlighting Brahmagulal's exceptional artistry – the ability to truly become the character he portrayed. It emphasizes that by embracing the form of a Digambar Muni, a role he chose for himself and refused to abandon, he truly became one and achieved his own spiritual liberation. The narrative reinforces the idea that the "form that does not change" is the true, spiritual self, attained through renunciation and dedication to the path of liberation.

Editorial Note (Samapadakiya):

The editorial section provides further context, identifying Brahmagulal as a real historical figure from the 16th-17th century near Firozabad. It details his education in various arts and scriptures, his talent in music and performance, and his family's distress over his "Baharupia" activities. It reiterates the minister's jealousy and the plot involving the prince and the lion's disguise. The editorial confirms that Brahmagulal, after killing the prince in his lion guise, took Digambar diksha and later, his friend Mathuramal also renounced the world after being influenced by Brahmagulal's spiritual realization. The editorial serves as a historical and thematic confirmation of the story's narrative.