Prassannatani Pankho

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Prasannatani Pankho" by Munishri Prashamrativijayji, based on the provided pages:

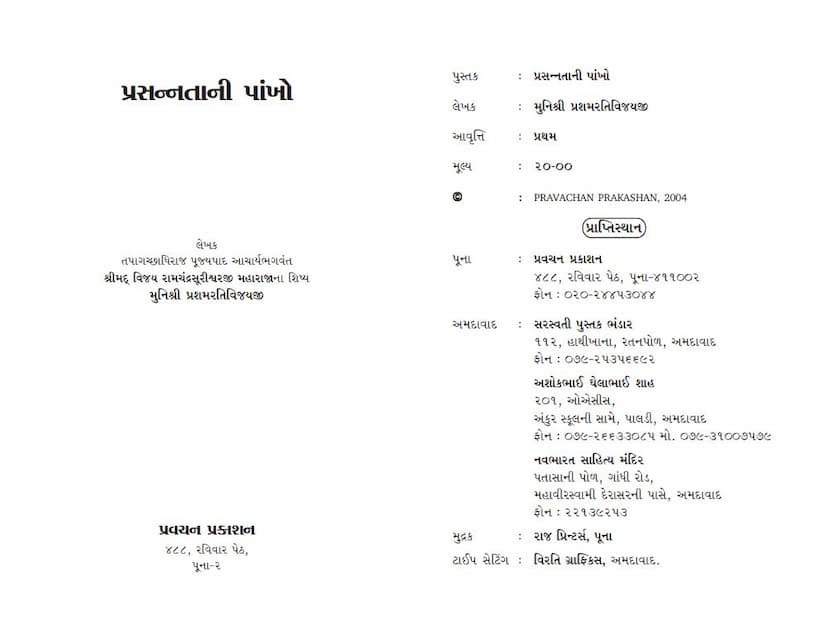

Book Title: Prasannatani Pankho (Wings of Happiness) Author: Munishri Prashamrativijayji Publisher: Pravachan Prakashan, Pune Catalog Link: https://jainqq.org/explore/009099/1

Overall Theme: The book aims to guide readers towards achieving lasting happiness by understanding and transforming their inner world, focusing on cultivating positive mental states, shedding negative thought patterns, and adopting a more balanced and mindful approach to life. It draws heavily on Jain philosophy and spiritual principles.

Summary of Key Chapters/Sections:

-

Introduction (Page 2): The preface likens happiness to wings that allow birds to soar. It suggests that weak thoughts and incomplete understanding are like folded wings; when unfolded, they reveal new colors. By understanding and decorating the mind, old wings shed, and new wings of happiness emerge, leading to an appreciation of life's joys. The book's articles, now in book form, aim to awaken new insights and bring new joy. It introduces the concept of three lives: the present, the post-life, and the life beyond the physical body (Moksha, Paramapad). The text emphasizes that our present life significantly impacts our post-life existence, and awareness in the present life is crucial for the ultimate spiritual state.

-

Prasannatani Pankho (Wings of Happiness) (Page 4): This section delves into the loss of happiness after childhood. It attributes this loss to the dominance of intellect and a misplaced trust in it. The intellect leads us to believe in our own inherent goodness and completeness, a belief that paradoxically hinders happiness. The author stresses the difference between being good and considering oneself good. The latter leads to pride, the need for external validation (certificates of goodness, praise), and unhappiness when it's not received. This pride also makes us blame others for mistakes while absolving ourselves, leading to complex justifications and a diminished sense of happiness. The text criticizes the ego of thinking oneself "great" simply because others seem "small." Instead, it advocates for shedding this false sense of superiority, embracing humility, and offering support without ego. True understanding comes from acknowledging our own limitations and not burdening others. The core message is that happiness is obstructed by the "planets" of prejudice (seeing others as bad/small) and pride (seeing oneself as good/great).

-

Dukhni Drishti (The Perspective of Suffering) (Page 5): This section argues that the expectation that suffering should not happen is the primary cause of unhappiness. Suffering is an inherent part of life, and resisting this fact causes more pain. It encourages introspection: why should suffering be avoided? Who decided it wouldn't come? The text suggests that suffering often arrives as a consequence of our past actions and that we often overlook the happiness we've given and focus on the suffering we've caused. True happiness, it claims, lies in detachment from expectations, similar to how a monk doesn't expect special glasses or milk. Unfulfilled expectations, even for simple things, lead to misery. The author posits that suffering isn't just a negative experience; it's a way to shed past burdens and clear old "trash." Experiencing hardship makes one humble and resilient; a life without struggle can't digest success. Suffering is defined as mental restlessness arising from broken expectations.

-

Dukhni Dosti (Friendship with Suffering) (Page 6): This part explores the limited help others can offer during suffering. It critiques the common tendency to run to others for solace, stating that this doesn't reduce suffering but rather stems from a childlike dependence. The text asserts that others, being fundamentally separate, cannot truly understand or share our emotional burden. The idea that sharing suffering lightens it is questioned; instead, it warns against infecting others with our negative thoughts. It emphasizes the importance of facing suffering independently. The author encourages finding joy even in difficult times by focusing on what we haven't lost, rather than what we have. The core advice is to avoid complaining and instead focus on internal solutions and personal resilience. Relying on others for support during suffering can create dependency, which is detrimental. True strength comes from facing challenges ourselves.

-

Samjo To Saru (If You Understand, It's Good) (Page 7-8): This section highlights the strength to face adversity. It advises facing suffering independently first, enduring what can be endured, and only seeking help as a last resort. It distinguishes between true resilience ("khumari") and helplessness ("lachari"). While accepting help is not wrong, begging for it is discouraged. We have a responsibility to keep those who care for us happy, not to burden them with our sorrows. The text emphasizes maintaining a calm exterior despite internal turmoil. True strength lies in facing challenges and taking responsibility for one's actions. It stresses the importance of self-reproach and self-correction rather than blaming others. A healthy person acknowledges their mistakes, learns from them, and strives for continuous self-improvement, not by outdoing others, but by surpassing their past selves. This self-awareness and dedication to growth are hallmarks of a "swasth" (healthy/balanced) individual, leading to contentment and a drive for gradual progress.

-

Manni Mavjat (Caring for the Mind) (Page 9-10): This section details how to transform oneself. It outlines steps for self-improvement: making a firm resolution, understanding the benefits of a healthy mind, maintaining honesty, and recognizing how personal well-being impacts others. It encourages self-reproach for mistakes, not with self-deprecation, but with a sincere acknowledgment of the error, its causes, and its consequences. It advocates for a structured plan of self-improvement, comparing past and future years, learning from mistakes, and striving for progress. It also emphasizes learning from the positive examples of others, acknowledging one's own shortcomings, and seeking spiritual guidance.

-

Saumyata ni Sarvani (The Spring of Gentleness) (Page 10-11): This part focuses on anger management. It advises against retaliating with anger, suggesting that a calm demeanor can be more effective. Anger is described as a deceptive state that arises from mental unrest and causes further unrest. It stresses the importance of listening and presenting arguments without agitation, as anger dissipates the core issue. The text advises exploring new opportunities when frustrated and warns that anger can create lasting resentment in others. It highlights the self-destructive nature of anger, leading to harsh words and a damaged reputation. The solution lies in controlling the first impulse to speak when angry, allowing anger to dissipate internally, and then calmly expressing oneself. Forgiveness and understanding, especially towards loved ones, are crucial. Anger towards strangers is pointless. True gentleness is seen as a prerequisite for decisive action, and inner peace is only achievable by letting go of anger.

-

Irsha no Ilaj (Cure for Envy) (Page 11-13): This section defines envy as the feeling of resentment arising from another's success or possession when we believe we deserve it more. It explains that envy stems from a sense of ego and comparison. The author questions the benefit of envy, stating it diminishes one's spirit, enthusiasm, and happiness, acting like slow poison. The key to overcoming envy is contentment with what one has. The text urges readers to recognize that others' progress does not diminish their own fortunes. It suggests focusing on one's own strengths and potential rather than comparing oneself to others. Envy is presented as a destructive emotion that arises from an unhealthy ego, leading to resentment towards others' good fortune and pleasure in their misfortunes. The antidote is self-acceptance, focusing on one's own goals, and practicing contentment.

-

Yadni Yatra (The Journey of Memory) (Page 14-15): This part discusses the nature of memory and its impact. It highlights how memories can either be a source of pain (when focused on past hurts and resentments) or a source of inspiration and learning. The author distinguishes between clinging to painful memories and using memories as a catalyst for positive change and self-improvement. It advocates for discarding memories that cause negativity and focusing on those that bring peace and joy. The text suggests that while some painful memories are unavoidable, the tendency to dwell on them can be overcome through mindful effort and a shift in perspective.

-

Ichha nu Injection (The Injection of Desire) (Page 15-16): This section addresses the nature of desires and how to manage them. It likens unchecked desires to inflation, constantly increasing and difficult to control. The solution proposed is similar to managing inflation: making conscious choices, being content with what one has, and not succumbing to every impulse. It advises differentiating between necessary desires and those that are superfluous, and to curb the latter. The author emphasizes that the pursuit of material possessions and endless desires leads to dissatisfaction. True happiness comes from recognizing one's current blessings and not being driven by an insatiable need for more. The text encourages setting clear, achievable desires, particularly those related to spiritual growth, and releasing those that are unlikely to be fulfilled.

-

Ger-Samaj ni Ganth (The Knot of Misunderstanding) (Page 16-18): This chapter focuses on the destructive nature of misunderstandings in relationships. It explains how a lack of harmony, often stemming from unexpressed resentments, can create a "knot" of misunderstanding. This knot leads to mistrust, prejudice, and indifference, poisoning relationships. The author stresses the importance of breaking these knots through open communication, forgiveness, and a willingness to see the good in others. It acknowledges the difficulty of overcoming long-standing misunderstandings but asserts that with sincerity and effort, relationships can be mended.

-

Apeksha ni Adalat (The Court of Expectations) (Page 18-19): This section delves into how expectations shape our happiness and unhappiness. It argues that most of our suffering arises not from external events but from unmet expectations. When expectations are unmet, we feel disappointment and unhappiness. The text encourages realistic expectations and a focus on intrinsic satisfaction rather than seeking happiness solely from external sources or the fulfillment of desires. It advocates for clarity in expectations, assessing their validity, and not projecting them onto others in a way that creates dependency or disappointment.

-

Abhipray ni Aalam (The World of Opinions) (Page 20-21): This chapter discusses the impact of opinions, both our own and those of others. It highlights how our opinions about others are often formed based on our relationships with them, rather than their inherent qualities. It cautions against forming hasty judgments and emphasizes the importance of objective evaluation. The text also touches upon how others' opinions can affect us and encourages maintaining inner peace regardless of external judgments. It suggests that while we cannot control others' opinions, we can control our reactions to them and strive to form our own opinions based on truth and understanding.

-

Te Bhagwan Banne Che (He Becomes God) (Page 21-22): This section, through a story about Lord Mahavir, illustrates the principle of karma and compassion. It suggests that those who cause suffering to others ultimately bring suffering upon themselves. Conversely, those who empathize with and wish well for those who cause them pain are on the path to spiritual elevation, akin to becoming divine. It emphasizes that our present suffering is often a consequence of past actions, and accumulating new negative karma by reacting with anger or resentment will only lead to future hardship.

-

Guru: Deevo, Guru: Devta (Guru: The Lamp, Guru: The Deity) (Page 23-24): This chapter emphasizes the profound importance of a Guru in spiritual progress. It states that a Guru's love is always available, but one needs the capacity to receive it. True connection with a Guru involves aligning one's actions and renunciations with theirs. It criticizes the tendency to seek worldly benefits from a Guru rather than spiritual guidance. The text highlights that the Guru's role is to guide one towards spiritual liberation (paramatma), often by teaching the art of detachment from desires. The Guru's teachings and sacrifices are meant to be emulated, not just intellectually understood. Following the Guru's path, even if difficult, is the true way to receive divine grace.

-

Vachanni Vachna (The Reading of Reading) (Page 24-25): This section focuses on the art and importance of reading. It emphasizes that true reading leads to contemplation and the formation of clear thoughts, rather than just passive consumption of information. It advocates for focused reading, selecting books wisely, and engaging with the text deeply. Regular reading is presented as essential for mental well-being and spiritual growth. It also stresses the importance of discussing what one reads to clarify understanding and gain new perspectives.

-

Vachhan Vishe (About Reading) (Page 25-26): This part continues the discussion on reading, offering practical advice. It suggests planning reading habits, choosing books based on their ability to foster virtuous thoughts and character, and seeking guidance from spiritual teachers for book selection. It recommends a structured approach to reading, setting time limits, taking notes, and reflecting on the learned material. The core idea is that reading should be a tool for self-transformation and spiritual development, not merely a pastime.

-

Bal Diksha: Ughta Suraj ni Puja (Child Initiation: Worship of the Rising Sun) (Page 26-28): This chapter beautifully explains the significance of child initiation into monastic life, likening a child to a rising sun. It emphasizes the purity and innocence of children and the responsibility of parents and guardians to nurture this innocence. It suggests that when parents cannot maintain their own purity, entrusting the child to a true spiritual guide (Sadguru) is the most loving act. This act ensures the child receives the spiritual upbringing they deserve, allowing them to blossom under the guidance of a master who can cultivate their innate purity and potential, leading them towards spiritual realization and liberation from the cycle of birth and death.

-

Putra Prasadini (Blessing of a Son) (Page 29-30): This section discusses the proper way to write letters to spiritual leaders (Maharaj Saheb). It provides guidance on addressing them respectfully, expressing well-wishes, sharing spiritual progress, and requesting their blessings or future visits. It emphasizes sincerity and devotion in communication, noting that spiritual leaders value the underlying sentiment more than the flowery language. The advice is to write from the heart, detailing spiritual experiences and expressing longing for their guidance.

In essence, "Prasannatani Pankho" is a guide to cultivating inner peace and happiness through self-awareness, detachment from worldly desires, mindful living, the pursuit of spiritual knowledge, and the grace of a Guru. It encourages a conscious effort to transform one's mind and perspectives to achieve lasting joy.