Pramana Naya Tattvaloka

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

This is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Pramana Naya Tattvaloka" by Himanshuvijay and Purnanadvijay, based on the provided pages. The text is a commentary (Balabodhini) on a foundational Jain philosophical work by Acharya Vādidēvasūri, focusing on logic, epistemology, and metaphysics within the Jain tradition.

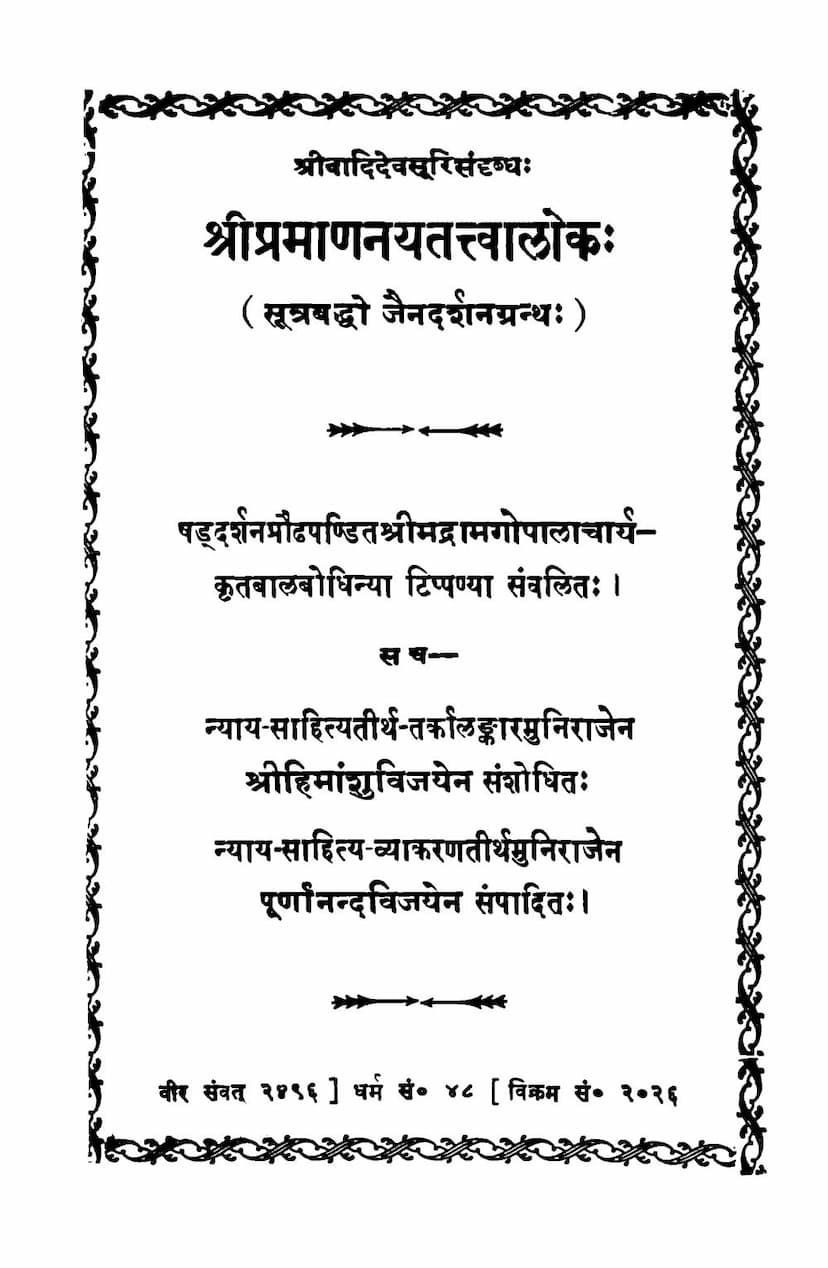

Book Title: Pramana Naya Tattvaloka (प्रमाणनयतत्त्वालोक) Author(s) of Commentary: Himanshuvijay (हिमांशुविजय), Purnanadvijay (पूर्णानन्दविजय) Original Author: Vādidēvasūri (वादिदेवसूरि) Publisher: Āmblipol Jain Upashray (आंबलीपोळ जैन उपाश्रय)

Overall Purpose and Context:

The publication of this book is presented as a significant event, aiming to make a previously scarce but essential Jain philosophical text accessible. The commentary is intended to clarify complex concepts for students of Pramana Shastra (the science of knowledge and valid cognition) and the Jain monastic community. The text is praised for its systematic exposition of Jain philosophy, particularly its epistemological framework.

Key Themes and Content Breakdown:

The book is structured into eight chapters, each delving into specific aspects of Jain philosophy:

-

Chapter 1: Pramana Lakshana (प्रमाणलक्षणम् - Definition of Pramana):

- Establishes the definition of Pramana (valid means of knowledge) as knowledge that is self-valid and distinguishes between what is to be accepted and rejected.

- Defines Naya (a perspective or partial standpoint) and the combined concept of Pramana-Naya.

- Discusses the purpose of the work as establishing the principles of Pramana and Naya.

- Argues against non-Jain theories of knowledge, particularly the Buddhist idea that sensory contact (sannikarsa) is the source of valid knowledge, asserting that knowledge itself is the true source.

- Emphasizes that Pramana must be definitive and free from doubt, refuting concepts like samaropa (superimposition).

-

Chapter 2: Pramana Bheda (प्रमाणभेद - Classification of Pramana):

- Classifies Pramana into two primary categories: Pratyaksha (direct perception) and Paroksha (indirect perception).

- Pratyaksha is further divided into:

- Sāṁvyavaharika Pratyaksha (सांव्यवहारिक प्रत्यक्ष - Conventional Direct Perception): Achieved through sensory organs (indriya-nibandhana) or the mind (anindriya-nibandhana). This includes the four stages of perception: Avagraha (initial grasping), Īhā (effortful examination), Avāya (conclusion/comprehension), and Dhāraṇā (retention).

- Pāramārthika Pratyaksha (पारमार्थिक प्रत्यक्ष - Ultimate Direct Perception): This is considered true direct perception and includes Avadhi Jnana (clairvoyance), Manahparyaya Jnana (telepathy), and Kevala Jnana (omniscience). These are attained through the purification of the soul and are not dependent on external senses.

- Argues for the reality of the soul (atma) as distinct from the body and the sensory organs.

- Refutes Buddhist theories that deny the existence of an enduring soul.

-

Chapter 3: Paroksha Pramana (परोक्ष प्रमाण - Indirect Means of Knowledge):

- Classifies Paroksha into five types:

- Smaraṇa (स्मरण - Memory): Recollection of past experiences.

- Pratyabhijñāna (प्रत्यभिज्ञान - Recognition): The knowledge that recognizes something as the same object experienced before, often with variations.

- Tarka (तर्क - Reasoning/Hypothetical Reasoning): Inferential process based on cause-and-effect or other logical relationships.

- Anumana (अनुमान - Inference): Deriving knowledge about something unseen based on its connection to something seen. This is further divided into svārtha anumāna (inference for oneself) and parārtha anumāna (inference for others, presented in a structured argument).

- Āgama (आगम - Testimony/Scripture): Knowledge derived from reliable sources (teachers, scriptures).

- Critiques the necessity of five-membered syllogisms (pañcāvayava) in inference, suggesting that two parts (pakṣa-hetu) are often sufficient for inferring a conclusion.

- Discusses the concept of vyāpti (pervasion) and its importance in inference.

- Classifies Paroksha into five types:

-

Chapter 4: Āgama Pramana and related Concepts (आगमप्रमाणम् - Testimony):

- Defines Āgama as knowledge derived from Āpta (a truthful and infallible authority).

- Discusses the nature of Āpta (both conventional and ultimate).

- Critiques the Vedic concept of apauruṣeya (unauthored) scripture, arguing for the pauruseya (authored) nature of the Vedas and the infallibility of Jain Tirthankaras.

- Explains that words (varna) are physical entities (pudgala).

- Introduces and explains the concept of Saptabhaṅgī (सप्तभंगी - The Syādvāda's Seven-Valued Predication): This is a cornerstone of Jain logic, describing how any reality can be viewed from seven different perspectives (e.g., it exists, it does not exist, it exists and does not exist, it is ineffable, etc.), each framed by the term Syād (perhaps or in some aspect). This reflects the Anekānta (non-one-sidedness) principle. The chapter explains the nuances and the philosophical basis for this structure.

-

Chapter 5: Pramāṇa Viṣaya (प्रमाणविषय - Subject Matter of Pramana):

- Discusses the nature of reality (vastu) as being characterized by both Sāmānya (सामान्य - Generality) and Viśeṣa (विशेष - Particularity), rejecting one-sided views (like the Vedantic emphasis on generality or Buddhist emphasis on particularity).

- Defines different types of generality: Tiryak Sāmānya (cross-category generality, like 'cowness') and Ūrdhva Sāmānya (upward generality, like 'substance' or 'existence' inherent in a substance).

- Defines Guṇa (गुण - Attribute) as co-existent qualities and Paryāya (पर्याय - Mode/Modification) as sequential states or changes.

- Argues that reality is an interplay of these general and particular aspects, attributes and modes.

-

Chapter 6: Pramāṇa Phala (प्रमाणफल - Result of Pramana):

- Explains the fruit or result of Pramana.

- Divides the result into Ānāntarya Phala (आनन्तर्य फल - Immediate Result), which is the removal of ignorance (ajñāna nivṛtti), and Pāramparya Phala (पारम्पर्य फल - Mediate Result), which are inclinations towards acceptance, rejection, or indifference towards objects based on the knowledge gained.

- For Kevala Jnana (omniscience), the mediate result is Audāsīnya (equanimity).

- Argues for the non-duality of the knower (pramātā) in the process of knowing and its results, emphasizing that the same entity experiences both the act of knowing and its consequences.

- Discusses various fallacies related to Pramana and its results, such as Pramāṇābhāsa (fallacies of valid cognition), including errors in perception (pratyakṣābhāsa), memory (smaraṇābhāsa), recognition (pratyabhijñānābhāsa), reasoning (tarkābhāsa), inference (anumānābhāsa), and testimony (āgamābhāsa).

-

Chapter 7: Naya (नय - Perspective/Standpoint):

- Defines Naya as a specific viewpoint or perspective that focuses on a particular aspect of reality while other aspects are temporarily set aside.

- Defines Nayābhāsa (fallacy of perspective) as a distorted or one-sided viewpoint that denies the validity of other perspectives.

- Classifies Nayas into two main categories:

- Dravyārthika Naya (द्रव्यार्थिक नय - Substance-Oriented Perspective): Focuses on the substance or underlying reality, often emphasizing its eternal and unchanging nature.

- Paryāyārthika Naya (पर्यायार्थिक नय - Mode-Oriented Perspective): Focuses on the changing modes or states of the substance.

- Further elaborates on Dravyārthika Naya as Naigama, Sangraha, and Vyavahāra.

- Further elaborates on Paryāyārthika Naya as Ṛjūtra, Śabda, Samabhirūḍha, and Evambhūta.

- Explains the importance of viewing reality from multiple perspectives (Anekānta) to achieve complete understanding and avoid fallacies.

-

Chapter 8: Vāda (वाद - Debate/Discussion):

- Defines Vāda as a structured discussion or debate aimed at establishing truth, involving participants with specific roles and objectives.

- Identifies the participants:

- Vādi (वादी - Debater/Proponent): The one initiating the debate.

- Prativādi (प्रतिवादी - Opponent): The one responding to the debate.

- Sabhyas (सभ्य - Audience/Judges): Those who assess the arguments.

- Sabhāpati (सभापति - Presiding Officer): The one who moderates the debate.

- Discusses the different motivations of a Vādi: Jijīṣu (one who desires victory) and Tattvanirṇinīṣu (one who desires to ascertain the truth).

- Outlines the rules and proceedings of a debate, emphasizing the importance of logical argumentation, adherence to accepted principles, and respectful discourse.

- Highlights the roles and responsibilities of each participant in ensuring a fair and productive debate aimed at discovering the truth.

Commentary and Editorial Notes:

The accompanying commentary (Balabodhini) by Munishri Purnanandavijay and Himansuvijay is highly valued for its clarity, logical explanations, and accessibility to students. The editorial notes acknowledge the efforts of various individuals and institutions in bringing this edition to light, including proofreaders, contributors of introductory essays, and the printing press. The preface emphasizes the educational value of this text for both aspiring scholars and the wider Jain community. It also advocates for the study of "Pramana Naya Tattvaloka" as a superior starting point for understanding Jain logic compared to other introductory texts.

Overall Significance:

"Pramana Naya Tattvaloka" is presented as a crucial text for understanding the epistemological foundations of Jain philosophy. Its systematic approach to knowledge, reality, and logical reasoning, along with its detailed exposition of concepts like Saptabhaṅgī and the various Nayas, makes it an indispensable resource for students and scholars of Jainism. The commentary ensures its continued relevance and accessibility for future generations.