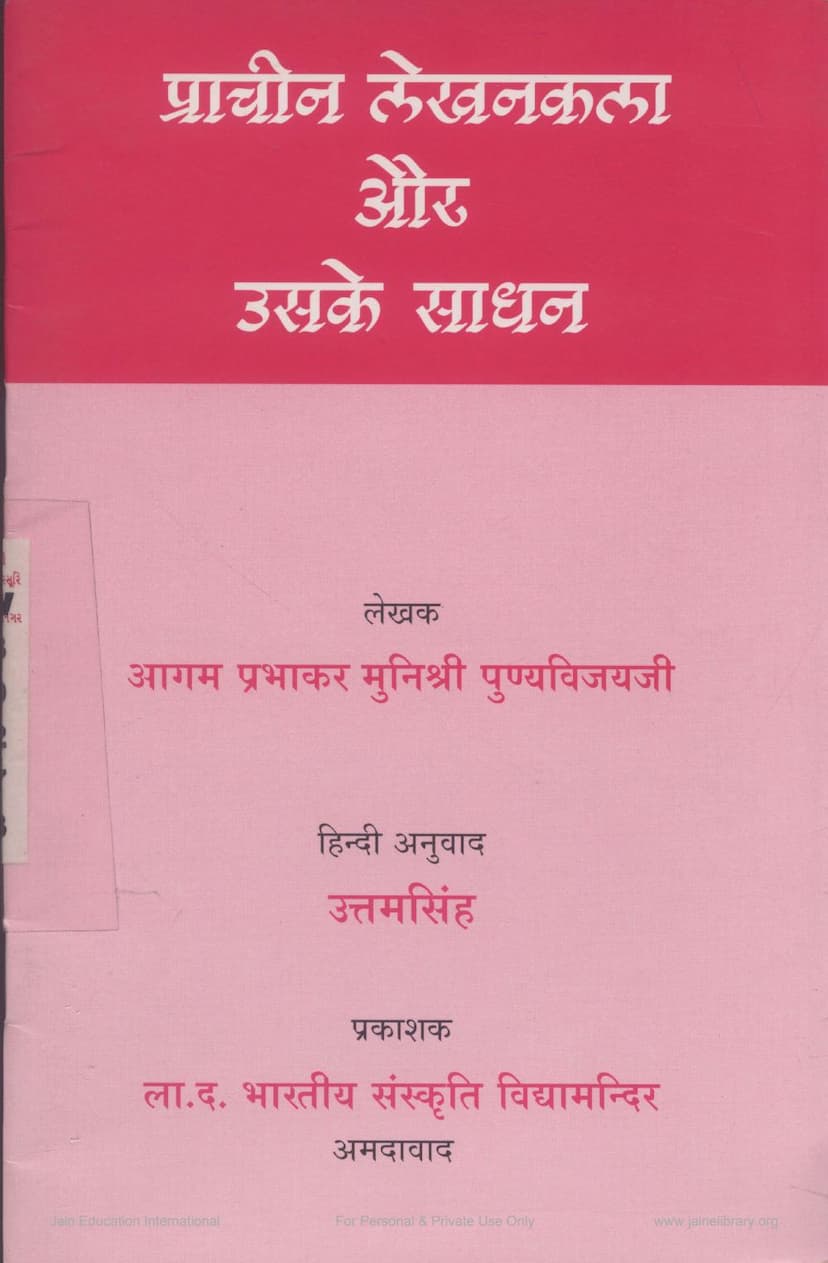

Prachin Lekhankala Aur Uske Sadhan

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Prachin Lekhankala aur Uske Sadhan" (Ancient Writing Art and Its Tools) by Muni Shri Punyavijayji, translated by Uttamsinh:

Overview:

This book is a valuable treatise on the historical art of writing and the tools used for it, particularly within the Jain tradition. Authored by the esteemed Jain scholar Muni Shri Punyavijayji, it addresses the fading of traditional writing methods due to the advent of printing and technology. The book aims to preserve the knowledge of these ancient arts and their associated materials for future generations.

Key Themes and Content:

-

The Decline of Traditional Writing: The author laments the loss of traditional calligraphy due to modern printing technology. He notes that generations of "Lahiyas" (scribes) who practiced this art professionally have shifted to other occupations, leading to a scarcity of skilled calligraphers capable of producing beautiful and accurate copies of manuscripts, especially those transcribed from ancient palm-leaf manuscripts.

-

The Importance of Preservation: The book highlights the critical need to understand and preserve these ancient writing arts and their tools. It emphasizes the rich cultural heritage embedded in manuscripts and the meticulous efforts of the Jain tradition in safeguarding its vast "Jnana Bhandars" (knowledge repositories).

-

Categorization of Writing Materials: The author systematically categorizes the tools and materials used in ancient writing:

-

Writing Surfaces:

- Palm Leaves (Talpatra): Distinguishes between "Khartal" (brittle, found in Gujarat) and "Shritad" (flexible, long, wide, found in Madras, Burma). Only Shritad leaves were suitable for manuscripts.

- Paper (Kagaz): Discusses various types of indigenous paper made across India and notes the preference for Ahmedabad and Kashmiri paper. It explains the process of preparing paper by "ghutai" (sizing) to prevent ink from spreading and the degradation of paper over time, especially with foreign varieties.

- Cloth (Kapda): Mentions its use for writing, particularly for talismans and diagrams, with an example of a cloth manuscript from the 13th century.

- Birch Bark (Bhojpatra): Primarily used for writing mantras and spells.

-

Writing Implements:

- Pens (Kalam): Describes the use of various types of reeds and bamboo ("baru") for making pens, noting their qualities and the importance of a good, unblemished reed. A Doha (couplet) is quoted regarding the qualities of a good writing reed.

- Correction Brushes (Pichhi): Explains their use in manuscript correction (e.g., changing letters, erasing, or overwriting). It specifically mentions brushes made from squirrel tail hair embedded in pigeon feathers as particularly effective due to the natural alignment of the hairs.

- Ruling Tools (Jujbal): A metal tool used for drawing lines on paper to guide writing, preventing the pen nib from wearing out too quickly.

- Styluses (Sui/Sariya): In regions like Burma and Madras where palm leaves were incised, sharp iron needles or rods were used instead of pens.

-

Inks (Syahi): This is a detailed section covering various ink recipes:

- Black Ink for Palm Leaves: Provides three types of recipes, including ingredients like triphala, iron filings, indigo, lac, and various plant extracts. It notes the difficulty in finding precise proportions and detailed instructions for some ancient recipes.

- Black Ink for Paper: Presents six types of recipes. The author emphasizes the first recipe as the most durable and suitable for preserving manuscripts for centuries. Recipes 2-4 are considered "medium" but can damage the manuscript over time, while recipes 5-6 are deemed "inferior" and should be avoided for long-term preservation.

- Gold and Silver Ink: Describes a method of creating gold and silver ink by grinding gold or silver leaf with gum water and sugar water.

- Red Ink (Hingolak): Details a meticulous process of purifying cinnabar (hingolak) by repeatedly washing it with sugar water to achieve a vibrant red color. The importance of precise gum concentration is highlighted.

- Yellow Ink (Harital): Explains the preparation of yellow ink from a specific type of harital by grinding it finely and mixing it with gum water.

- White Ink (Safeda): Prepared by mixing powdered white lead with gum water.

- Ashtagandha (Eight Fragrances): Used for writing mantras, it is a mixture of eight ingredients including agar, tagar, gorochana, musk, red sandalwood, sandalwood, sindoor, and kesari.

- Yakshakardam: Also used for writing mantras, it's a mixture of eleven ingredients including sandalwood, saffron, agar, baras, musk, markankol, gorochana, hingolak, ratanjani, gold leaf, and amber.

-

-

Ink Preparation and Usage:

- It details how to prepare inks, including the crucial role of gum (khair, babool, neem) and the caution against using "dhava" gum which damages ink.

- The use of ingredients like "Dairli" (a plant extract) for making ink more luminous and the proper method for mixing and grinding are discussed.

- Special attention is given to the use of Laakharas (lac resin) and Biya-ras (from Biya wood) for enhancing ink quality.

- The text describes how gold and silver inks were applied to colored backgrounds using a brush over a base of harital or safeda, and then burnished with agate or touchstones for brilliance.

-

Manuscript Structure and Types:

- Book Types (Pustak-Panchak): Cites Haribhadra Suri's classification of five types of manuscripts: Gundi (thick, rectangular), Kachchhapi (thin at ends, thick in middle), Mushti (small, cylindrical or square), Samputaphalaka (with covers), and Sripati (thin leaves, tall).

- Layouts: Explains "Tripaath" (three parts – main text in the center, commentary above and below) and "Panchapaath" (five parts – main text in the center, commentary above, below, and in margins on both sides). "Sudha" refers to a continuous writing style without divisions. The practice of Tripaath and Panchapaath likely began around the 15th century.

-

Scribes' Beliefs: The author shares a fascinating insight into the superstitious beliefs of scribes ("Lahiyas"). They would avoid writing certain letters when taking breaks, believing those letters brought ill fortune. Conversely, they favored writing certain other letters for good luck and productivity. Marwari scribes, in particular, favored the letter "Va" for such purposes.

-

Palm-Leaf Manuscript Numerals: The book presents a section on the different numeral systems used in palm-leaf manuscripts, referencing "Bhartiya Prachin Lipimala." It provides examples of digits for units, tens, and hundreds, noting that they were often written vertically rather than horizontally.

-

Manuscript Preservation (Pustakarakshan):

- Protection from Moisture: Explains that gum in the ink can cause pages to stick, especially during the monsoon. Manuscripts were bound tightly and kept in protective cases (wood, leather, or paper) inside cupboards or chests. Bhandars were typically opened only when necessary during the rainy season.

- Dealing with Sticking Pages: Offers methods for separating stuck pages, including using air circulation or slight dampness for paper books, and damp cloth for palm-leaf manuscripts, emphasizing patience to avoid damage.

- Protection Slokas: Cites verses written by scribes themselves on how to protect manuscripts from water, fire, rodents, careless handling, and damage.

- Author's Disclaimer: Includes verses where authors express humility and acknowledge potential errors.

-

Gyan Panchami: The text discusses the Jain festival of Gyan Panchami (Kartik Shukla Panchami for Shvetambars), highlighting its significance for manuscript preservation. It was a day for airing out manuscripts, removing moisture (bhej), cleaning bhandars, and preventing infestations like termites. People would observe fasts and participate in these preservation activities. The author notes a decline in the original practice, with some communities now focusing more on ritualistic worship of books rather than their physical maintenance.

-

Conclusion: The author concludes by urging institutions like Gujarat Vidyapeeth and Gujarat Puratatva Mandir to inspire individuals to engage with and respect written literature, ensuring that the appreciation for ancient texts does not vanish in the age of printing.

Overall Significance:

"Prachin Lekhankala aur Uske Sadhan" is a seminal work that meticulously documents and preserves the knowledge of ancient Indian writing arts and materials. It serves as a vital resource for scholars, historians, and anyone interested in the material culture of ancient texts, particularly within the rich intellectual heritage of Jainism. The author's deep personal engagement with manuscripts and his dedication to scholarly research are evident throughout the text.