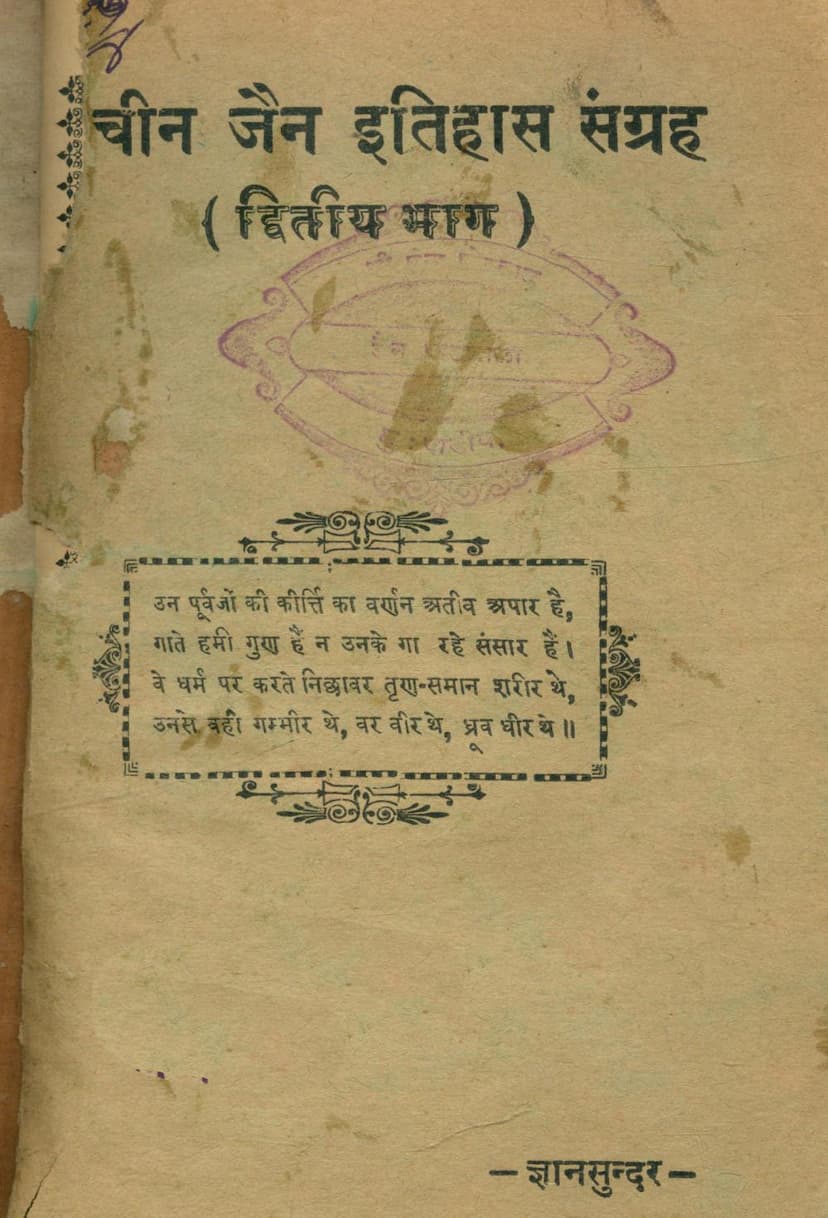

Prachin Jain Itihas Sangraha Part 02 Jain Rajao Ka Itihas

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

This document is the second part of the "Prachin Jain Itihas Sangraha" (Collection of Ancient Jain History) by Muni Gyansundar Maharaj, focusing specifically on the history of Jain kings.

The book begins with an ode to the ancestors who sacrificed their bodies for Dharma. It is published by Ratnaprabhakar Gyanpushpamala in Phalodi (Marwar) in Vikram Samvat 1992 (AD 1935).

The core of the book is a lengthy dialogue between two young men, Shantikumar and Kantikumar, discussing the nature of historical evidence.

- Kantikumar is a staunch advocate for pratyaksh praman (direct evidence), such as inscriptions, copper plates, coins, and contemporary written texts by credible individuals. He dismisses genealogies and ballads (like those of kulaguru and vahi-bhat) as unreliable due to factual inconsistencies, missing information, and the prevalence of hearsay. He struggles to find sufficient direct evidence for ancient history.

- Shantikumar argues for a broader definition of evidence, including paroksh praman (indirect evidence) like agams (ancient scriptures) and anumans (inference/deduction). He emphasizes that while direct evidence is crucial, indirect evidence is necessary to bridge gaps and understand the broader context. He uses the example of missing links between inscriptions of different kings to illustrate the need for inferential reasoning. He points out that even prominent historical works like those of Mehta Nensi and Tod Rajasthan, though containing errors, have been foundational for later scholarship by incorporating a wider range of sources. Shantikumar also introduces the concept of agams to include pottavalis and genealogies, suggesting that even if not perfectly accurate, they offer valuable clues.

The dialogue then shifts to the existence of Lord Rishabhdev, the first Tirthankara. Kantikumar, with his strict adherence to direct evidence, expresses ignorance about Rishabhdev, stating he hasn't encountered any evidence for him in his research. Shantikumar expresses dismay, highlighting Rishabhdev's significance as an ancient figure revered by Jains, Hindus, and Muslims, and points to ancient sculptures and inscriptions as proof.

The conversation then touches upon the reliability of memory and family history. Kantikumar insists on documentary proof for each generation of his ancestry. Shantikumar uses this to illustrate the necessity of inference: just because a father's name isn't explicitly recorded in a document doesn't mean he didn't exist, as lineage is a natural inference. He applies this logic to the Tirthankaras, arguing that even if direct evidence for earlier Tirthankaras is scarce, their existence is inferable and supported by agams. He suggests that what is considered indirect evidence today (like agams) can become direct historical evidence as research progresses, citing the example of recent discoveries supporting the historical existence of Lord Neminath. Shantikumar also addresses the seemingly impossible physical dimensions and lifespans of ancient figures, suggesting that considering the gradual changes in human physique and longevity over millennia, such claims are not entirely unbelievable, referencing archaeological findings from Harappa as a parallel.

The latter part of the book (starting from Page 17) shifts from the philosophical discussion to a detailed compilation of Jain kings and their patronage of Jainism. It begins by asserting that Jainism was once a national religion, propagated by ascetics across India and even to other countries like Austria, America, Mongolia, Egypt, China, Japan, and Mecca. The author laments the lack of continuous historical records for the actions of these kings.

The book then lists numerous kings who were devout followers or promoters of Jainism, often citing specific Jain scriptures (like Niryavalika, Bhagavati Sutra, Uttaradhyayan Sutra, Kalpa Sutra, Thanaayanga Sutra, Rayapaseṇi Sutra, Vipaka Sutra, Kevalaya-mala, Prabhavaka Charitra, Upakesa Gaccha Pattavali, etc.) as sources for their information. These rulers span various regions of ancient India and different historical periods, from the time of Lord Mahavir to later centuries. The list includes prominent figures like:

- Chetaka of Vaishali

- Udai of Magadha

- Chandpradyota of Avanti

- Samyati of Kapilpur

- Dashanbhadra of Dashanpur

- Yugabahu and Menrayi of Sudarshanpur

- Dadhi-vahan of Champanagari

- Shankh of Kashi

- Nami of Mithila

- Karkandu of Kalinga

- Dumai of Panchal

- Niggai of Gandhara

- Bhalabhadra of Sushrava Nagar

- Vijayseen of Polaspur

- Adinshatru of Savatthi Nagar

- Chandrapal of Sankhetpur

- Nandivardhan (Mahavir's brother)

- Santanik and Mrigavati of Kosambi

- Jayketu of Kapilpur

- Dharmasheel of Kanchannagar

- Adinshatru and Dharani of Hastinapur

- Dhanbah and Saraswati of Rishabhpur

- Veer Krishnamitra and Rati Devi of Virpur

- Vasavdatta and Krishnadevi of Vijaypur

- Apratihata of Sogandhika Nagari

- Priychandra of Kanakpur

- Bal of Mahapur

- Arjun of Sughosh Nagar

- Datta and Rattavanti of Champanagari

- Mitranandi and Shri Kanta of Saket

- Seta of Amalkampa

- Pradeshi of Shvetambika

- Shiva (king of Hastinapur who converted)

- Viranga and Virjas

- Hastipal of Pavapuri

- Prasenjit, Shrenik (Bimbisara), Konak (Ajatshatru), Udai (mentioned as great devotees of Mahavir)

- Jaysen of Shrimaal Nagar

- Padmasen of Padmavati Nagar

- Chandrasen of Chandravati Nagar

- Shivsen of Shivpuri

- Utpaldev of Upkeshpur

- Kanaksen of Kolapur Pattan

- Rudrat of Shiva Nagar

- Shivdutt of Bhadravati

- Nanda Kings of Patliputra

- Maurya Emperors Chandragupta, Bindusara, Ashoka, and Samprati (credited with spreading Jainism to distant lands)

- Mahameghavahan Chakravarti Kharavel of Kalinga

- Vijaysen of Vijaypur Pattan

- Shankhpal of Sankhpur Nagar

- Mahabali of Mandovar

- Vidharta of Ujjain

- Balmitra and Bhanumitra of Ujjain

- Nabhsen of Ujjain

- Veersingh of Dharavas

- Vikramaditya of Ujjain (credited with establishing the Vikram era, a patron of Jainism and scholar Siddhasen Divakar)

- Devpal of Kurmarpur

- Murudan of Patliputra

- Prajapati of Vilaspur

- Krishnaraj of Mankhet

- King of Guda Shastra

- Dahadraj of Patliputra

- Shalyaditya of Vallabhnagari

- Jayketu of Sopara Pattan

- Kardapi of Kolhapur Pattan

- Dhruvasena of Anandpur

- Dhaval of Jabali pur

- Chitragend of Kanyakubja

- Hunn King Toramin of Bhinmal

- Arimardan of Velapur

- Harshadev of Banaras (converted by Manatung Suri)

- Kaku of Marukot

- Shurdev of Ranakhdurg

- King of Tribhuvan Nagar

- Ghoshal of Sindh

- Vijayvant of Sakkhpur

- Bhan of Bhinmal

- Aam of Gaurigiri (Gwalior)

- Vakpati of Mathura

- Dharmasheel of Gaud-Desh

- Vanraj Chavda of Patan

- Amoghavarsha of Mankhet

- Shatrushalya of Nanakpur

- Rao Rakhecha of Kaler

- Jaitrasimha of Kiratkupa

- Bhoj of Kannauj

- Kakuk of Mandor

- Viddagdhraj of Hastikundi

- Dhaval of Hastikundi

- Rulers of Rashtrakuta, Chalukya, Kalchuri, Pallava, Hoyala, Kadamba, Ganga, Pandya, and Chola dynasties (mentioned as patrons of Jainism)

- Elak of Elachipur

- Chamundaray of Patan

- Bhoj of Dharanagari

- Jaykeshi of Karnatak

- Rao Dha of Naradpuri

- King of Dumrel Nagar of Sindhu Prant

- Singhavali of Marakot

- Alhadan of Nagpur

- Siddharaj Jaysingh of Pahana

- Kumarpal of Padan (pupil of Hemchandracharya, great propagator of Ahimsa)

- Jaitrasimha of Chandravati

- Prathuna of Shakambhari

- Samarsingh of Suvarnagiri

- Mohensingh of Mandovar

- Prataprudra of Kalinga

- Emperor Akbar (converted by Acharya Vijay Heer Surishwar, who obtained decrees for protection of Jain sites)

The author concludes by stating that this compilation is brief due to the public's lack of interest in lengthy texts, weakened mental capacity, time constraints, and a diminished love for history. The intent is to benefit the general populace through these concise tracts. The book emphasizes Jainism's historical connection with Kshatriyas and its widespread influence, asserting its status as a national religion in ancient India.