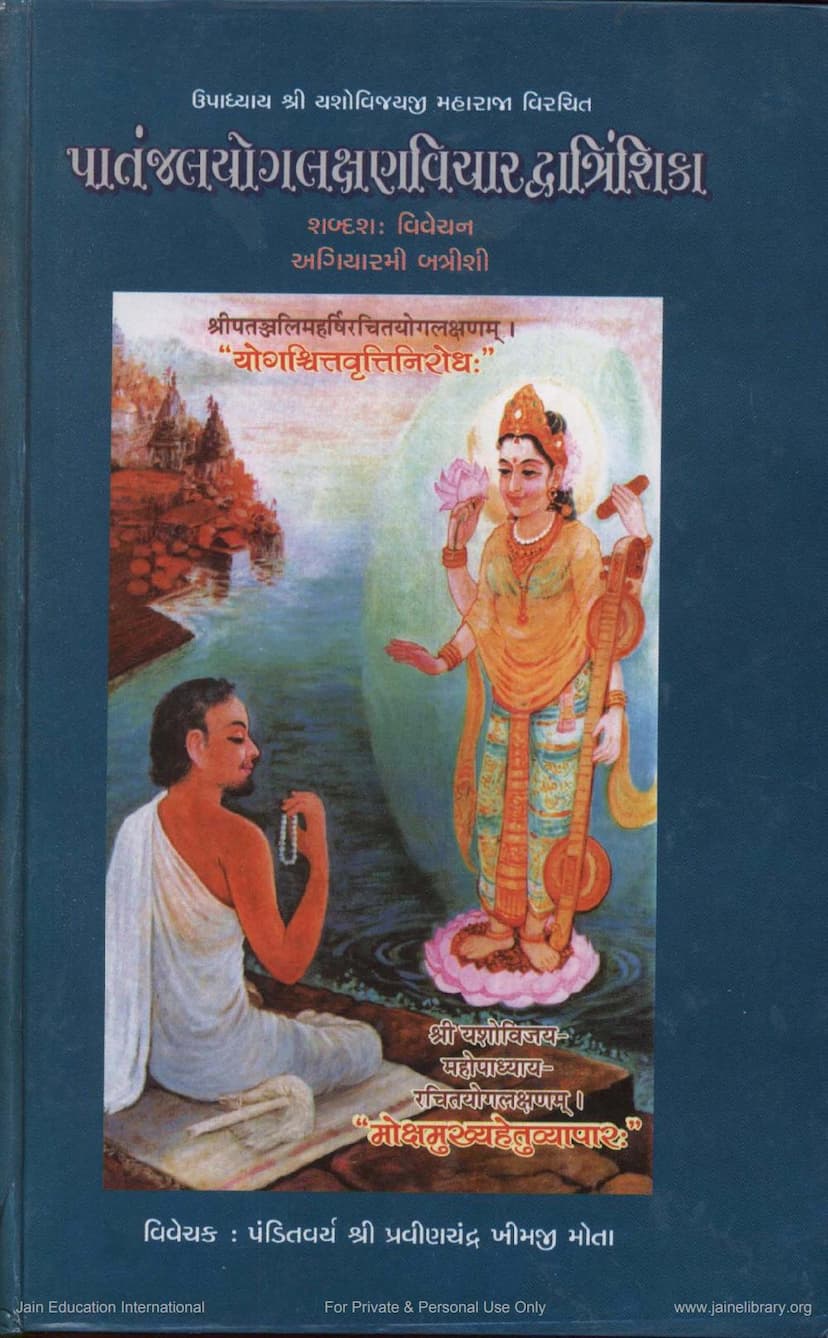

Patanjalyoglakshanvichar Dvantrinshika

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Patangalyoglakshanvichar Dvātrinśikā" by Yashovijay Upadhyay, with commentary by Pravinchandra K. Mota, published by Gitarth Ganga:

Title: Patangalyoglakshanvichar Dvātrinśikā (An examination of the definition of Yoga according to Patanjali, the eleventh chapter of Dvātrinśikā)

Author of the original work: Upadhyay Shri Yashovijayji Maharaj

Commentator/Editor: Pandit Shri Pravinchandra Khimji Mota

Publisher: Gitarth Ganga, Ahmedabad

Overview:

This book is a detailed, verse-by-verse commentary (Shabdashah Vivechan) on the eleventh chapter of Mahamahopadhyaya Shrimad Yashovijayji Maharaj's expansive work, the Dvātrinśikā. This specific chapter, "Patangalyoglakshanvichar Dvātrinśikā," focuses on analyzing and critiquing the definition of Yoga presented by the sage Patanjali in his renowned Yoga Sutras, specifically the famous aphorism "Yogas cittavṛttinirodhaḥ" (Yoga is the cessation of the fluctuations of the mind).

Core Purpose and Argument:

The fundamental aim of this chapter is to:

- Clarify Patanjali's definition of Yoga: Yashovijayji Maharaj meticulously breaks down Patanjali's definition, explaining the concepts of citta (mind), vṛtti (fluctuations/modifications), and nirodha (cessation).

- Critique Patanjali's definition from a Jain perspective: The central thesis is to examine how Patanjali's definition of Yoga aligns with or deviates from the core tenets of Jain philosophy, particularly regarding the nature of the soul (Ātmā), the reality of the world, and the path to liberation (Moksha).

- Establish the supremacy of the Jain understanding of Yoga: By highlighting perceived inconsistencies or limitations in Patanjali's (and by extension, Sankhya's) views when seen through the lens of Jain metaphysics, the work aims to reinforce the Jain perspective on Yoga as the ultimate path to self-realization and liberation.

Key Areas of Analysis and Critique:

The commentary delves into several complex philosophical points, primarily engaging with the Sankhya-Yoga school of thought:

- Nature of the Soul (Ātmā): The text extensively discusses whether the soul (Purusha in Yoga/Sankhya terminology) is intrinsically unchanging (kūṭastha nitya) or if it has a degree of inherent potential for transformation (kañicit pariṇāmī). Yashovijayji Maharaj, reflecting Jain doctrine, argues that the soul, while having an unchanging essential nature, also undergoes transformations in its states or modifications (paryāya). Patanjali's strict adherence to an unchanging, immutable soul, they argue, creates logical inconsistencies when explaining the process of Yoga and liberation.

- The Role of Nature (Prakriti): The text scrutinizes the Sankhya-Yoga concept of Prakriti as the source of all material reality. A major point of contention is the Sankhya-Yoga view that Prakriti is singular and all-pervasive. Yashovijayji Maharaj highlights the logical problem: if Prakriti is one, then the liberation of one soul should imply the liberation of all, or none, creating an untenable situation.

- The Mechanism of Perception and Action: The work explores how consciousness (citi) interacts with the material world. Patanjali's view of the Purusha's proximity (sannidhāna) enabling Prakriti's modifications to manifest as consciousness is analyzed. The commentator questions how an immutable Purusha can be the cause or initiator of manifestation.

- The Problem of "Uncaused Cause": The text examines the Sankhya-Yoga idea that Purusha is uncaused and un-acting. If Purusha is the silent witness and the cause of manifestation, but itself remains passive, this creates a philosophical challenge in explaining the process of suffering and liberation.

- The Nature of Yoga: While acknowledging Patanjali's definition of Yoga as the cessation of mental fluctuations, Yashovijayji Maharaj's own definition of Yoga, presented in the tenth chapter, is emphasized: "the activity that serves the primary purpose of liberation." This highlights a difference in scope and emphasis, with the Jain view potentially encompassing a broader range of spiritual practices and states leading to liberation.

- The Critique of "Purushartha" (Purpose of Purusha): The text questions the Sankhya-Yoga idea that Prakriti acts for the purpose of Purusha. If Prakriti is inert (jaḍa), how can it have an inherent purpose to act for Purusha? This is seen as an unphilosophical assertion.

- The Five Modifications of the Mind (Citta Vṛttis): Patanjali's classification of mental modifications—pramāṇa (correct cognition), viparyaya (misconception), vikalpa (imagination/verbal delusion), nidrā (sleep), and smṛti (memory)—is explained. The text dissects the nature of each, particularly challenging the conceptualization of vikalpa and its relation to linguistic cognition.

- The Means to Cessation (Abhyāsa and Vairāgya): Patanjali's prescribed methods for achieving the cessation of mental fluctuations—disciplined practice (abhyāsa) and detachment (vairāgya)—are discussed. The text distinguishes between lower (apara) and higher (para) forms of detachment, and explores the efficacy of practice.

- The Jain Perspective on Liberation: The Jain view emphasizes the soul's inherent purity and its obstruction by karmic matter. Liberation is achieved through the removal of these karmic veils, leading to the soul's natural state of omniscience and bliss. The critique of Patanjali's Yoga often points to how the Sankhya-Yoga framework, with its dualistic realism of Purusha and Prakriti, and its conception of the soul's immutability, differs significantly from the Jain understanding of karma, soul transformation, and the path to liberation.

- Reconciling Differences: Throughout the commentary, Yashovijayji Maharaj strives to show how the Jain framework offers a more coherent and comprehensive explanation for the phenomena of existence, suffering, and liberation, often by showing how the Sankhya-Yoga concepts lead to paradoxes or incompleteness when scrutinized.

Structure and Style:

The book meticulously follows the structure of the original Sanskrit text, providing the verse, its transliteration, an explanation of the Sanskrit words (anvayārtha), the meaning of the verse (shlokārtha), the original Sanskrit commentary (ṭīkā), and a Gujarati interpretation (bhāvārtha). Pandit Pravinchandra Mota's commentary is erudite, drawing upon vast knowledge of Jain scriptures and philosophical traditions to elucidate Yashovijayji Maharaj's arguments.

Significance:

This work is invaluable for understanding the Jain critique of influential non-Jain philosophical systems, particularly Yoga and Sankhya, which have had a significant impact on Indian thought. It showcases Yashovijayji Maharaj's intellectual prowess and his deep commitment to establishing the logical consistency and superiority of Jain philosophy. The commentary by Pandit Mota makes these complex arguments accessible to scholars and practitioners interested in comparative Indian philosophy and Jainology. The book highlights the sophisticated philosophical debates that have taken place within Jainism regarding the nature of reality and the path to liberation.