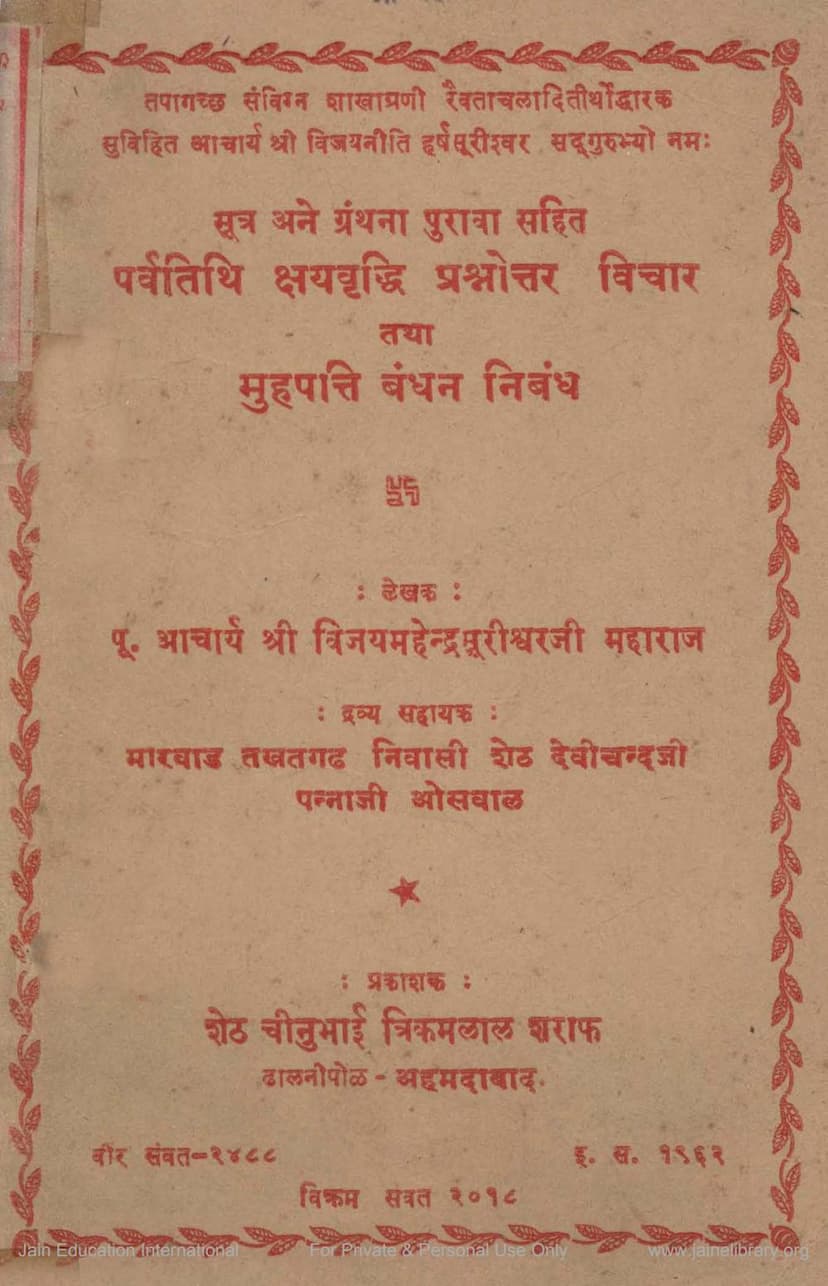

Parvatithi Kshay Vruddhi Prashnottar Vichar Tatha Muhpatti Bandhan Nibandh

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Parvatithi Kshay Vruddhi Prashnottar Vichar tatha Muhpatti Bandhan Nibandh" by Acharya Hemchandrasuri, based on the provided pages:

Overall Context:

This book, published in 1962 (Veer Samvat 2488, Vikram Samvat 2018), is a compilation of discussions and essays related to Jain principles, specifically addressing the nuances of Paryushan (festival) dates (Parva Tithi) and their perceived "decay" (Kshay) or "growth" (Vruddhi), and the practice of wearing a Muhpatti (mouth covering). The work is dedicated to the lineage of Acharya Shri Vijaynitisurishwar and is financially supported by Seth Devichandji Pannaji Oswal of Takhatgarh.

Key Sections and Their Summaries:

1. Dedication and Publisher Information (Pages 1-3):

- The book begins with traditional reverential salutations to the lineage of Acharya Shri Vijaynitisurishwar, highlighting his role as a reviver of the Revatachal Tirth and a leading figure in the Samvigna branch of the Tapagachha.

- It clearly states the title, author (Acharya Shri Vijaymahendrasurishwarji Maharaj), patrons (Seth Devichandji Pannaji Oswal), and publisher (Seth Chinubhai Trikamlal Saraf).

- The publication details (location, Veer Samvat, Vikram Samvat, and Gregorian year) are provided.

2. Life History of Seth Pannalalji Dhiraji and Family (Pages 6-9):

- This section provides a biographical sketch of Seth Pannalalji Dhiraji of Takhatgarh and his family.

- Takhatgarh is noted as a prominent Jain city. Seth Dhiraji and his wife Indumati were devout Jains.

- They had four sons: Achala, Pannalal, Okchand, and Kesharimal, who lived in harmony and prosperity.

- The text emphasizes the importance of using wealth for good deeds, quoting a verse that contrasts misers who bury wealth with saints who use it for religious purposes like supporting Gurus and temples.

- Seth Pannalalji and his brothers were generous patrons of religious activities. They undertook the construction of a magnificent temple in Takhatgarh, costing a significant amount. The foundation was laid in Samvat 1973 and the consecration (Pratishtha) took place in Samvat 1980, attended by a large gathering.

- The temple featured grand idols of Lord Rishabhdev, Lord Parshvanath, and Lord Shantinath, as well as idols of Lord Neminath and Lord Mahavir. A shrine for "Dadaji" (likely a revered saint) was also established.

- Seth Pannalalji was born in Samvat 1931. He also facilitated the construction of a Vihara (Upaashray/Dharmashala) for visiting monks and nuns and Jain pilgrims. He organized a large pilgrimage (Sangh) to Siddhachal.

- His religious activities included charitable donations, worship, serving monks and nuns, and helping fellow Jains.

- Seth Pannalalji's wife, Bai Magani, passed away in Samvat 1986, and Seth Pannalalji passed away in Samvat 2002.

- His son, Seth Devichandji, continues the tradition of using wealth for religious purposes, is a leader in the Takhatgarh Sangh, and is a respected businessman in Bangalore.

- The book acknowledges Seth Devichandji's financial contribution of ₹327 towards the publication of this useful book and encourages others to follow his example of using wealth for good.

3. Question and Answer on Parva Tithi Kshay/Vruddhi (Paryushan Dates and their Changes) (Pages 10-28):

This is the core of the book, addressing a complex theological and calendrical issue:

- Origin of Tithi (Date) in Jainism:

- Question 1: Where does the concept of tithi originate in Jainism, and what is its measurement?

- Answer: Citing the Surya Prajnapti and Jyotish Karanjak Sutras, the text states that tithi originates from the Moon (Chandra). Its measure is approximately 59 ghadi (a unit of time) and one muhurta (a subdivision of time) divided into 31 parts. This measure means a tithi cannot span two sunrises, thus Jainism does not accept the "growth" (Vruddhi) of a tithi. The calculation shows a tithi is approximately 29 muhurta and some parts of a muhurta.

- Laukik (Conventional) Jyotish vs. Jain Jyotish:

- Question 2: What is the measure of tithi in conventional Vedic Jyotish?

- Answer: Conventional Jyotish bases tithi on the Moon's movement, which can vary between 54 and 66 ghadi. This variation allows a tithi to span two sunrises, leading to the "growth" (Vruddhi) of tithi in conventional calendars.

- Kshay (Decay/Loss) of Tithi in Jainism:

- Question 3: Does Kshay of tithi occur according to Jain principles?

- Answer: Yes, according to the Surya Prajnapti and Jyotish Karanjak Sutras, the measure of a tithi is slightly less than a full day (Ahoratra). This leads to a kshay of one tithi every two months. The text explains that each day, a 62nd part of a day-night cycle is related to the "decay" night (Avama/Kshaya Ratri). Over 62 days, one such decay night occurs, resulting in the 62nd tithi being "lost" or observed as a "decayed" tithi in common parlance. A verse states that if two tithis are completed within one day-night, the second tithi experiences kshay.

- Kshay/Vruddhi of Parva Tithis (Paryushan Dates):

- Question 4: Does kshay or vruddhi of parva tithis occur according to Jain astrology, or only in conventional calendars?

- Answer: Yes, kshay of parva tithis occurs according to Jain principles, and both kshay and vruddhi occur in conventional calendars. The Bhagavati Sutra identifies Ashtami (8th day), Chaturdashi (14th day), Amavasya (new moon), and Purnima (full moon) as the primary parva tithis.

- Handling Kshay/Vruddhi of Parva Tithis:

- If a parva tithi experiences kshay, the kshay should be applied to the preceding non-parva tithi. This is based on the saying from the Lokaprakasha by Acharya Umashvati: "If there is kshay of a parva tithi, then the preceding tithi should be observed." For example, if Ashtami occurs on the 7th day, the 7th day should be observed as Ashtami.

- If a parva tithi experiences vruddhi, the subsequent non-parva tithi should be observed. This is supported by commentary on the Kalpa Sutra, which states that if two Chaturdashis occur, the first is disregarded, and the ritual is performed on the second. The term "avaganayya" (to disregard) implies treating the first Chaturdashi as non-parva.

- This principle applies to Amavasya and Purnima as well; if they kshay, the preceding Teras (13th day) is observed. If they have vruddhi, the following Teras is observed.

- Origin of the Saying "Kshaye Purva Tithi Karyaa":

- Question 5: Are the two phrases of Acharya Umashvati's saying ("Kshaye Purva Tithi Karyaa, Vruddhau Karyaa Tatha Uttara") his own composition?

- Answer: The book suggests the first part ("Kshaye Purva Tithi Karyaa") is likely by Umashvati, but the second part ("Vruddhau Karyaa Tatha Uttara") might be by an earlier Acharya for organizing the calendar. However, it's accepted tradition.

- Absence of Siddhantic Commentary:

- Question 6: Since when is the absence of Siddhantic commentary presumed?

- Answer: It's believed that Siddhantic commentary was present during Umashvati's time and his disciples. The absence might have started around the 14th century, before Jinaprabhasuri.

- Handling Kshay/Vruddhi of Parva Tithis in Laukik Panchangs:

- Question 7: If Amavasya or Purnima experiences kshay after Chaturdashi in a conventional calendar, how should the parva be observed?

- Answer: Following the principle "Kshaye Purva Tithi Karyaa," the Teras (13th day) should be observed as the celestial Amavasya or Purnima. If Amavasya or Purnima has vruddhi, then the Teras that follows the conventional Chaturdashi should be considered the Amavasya or Purnima.

- Question 8: If Amavasya or Purnima experiences kshay, the kshay is applied to the 13th. If they have vruddhi, it's applied to the 13th. Is this interpretation correct?

- Answer: The text elaborates on the nuance of the phrase "Teyodashyachaturdashyoḥ" in the Hirprashna text. It suggests that for Amavasya kshay, the ritual is performed on the 13th. For Purnima vruddhi, it's also on the 13th, and if forgotten, on the 1st. The dual use of the 7th case ("Teyodashyachaturdashyoḥ") is significant, implying that the Purnima ritual should follow Chaturdashi, not precede it. Therefore, for Purnima vruddhi, it means observing the tithi on the 13th.

- Question 9: If Amavasya or Purnima experiences vruddhi in a conventional calendar, how should the parva be observed?

- Answer: According to the tradition of Umashvati, "Vruddhau Karyaa Tatha Uttara," the preceding non-parva tithi (Teras) is observed as the parva. This maintains the continuity of the parva. If the first Purnima (in case of a double Purnima) is observed on the 14th (as a substitute for the celestial Purnima) and then the actual Purnima is observed, it breaks the intended sequence. Therefore, to maintain the unbroken sequence, the tithi on the 13th is observed.

- Acceptance of Tithi Changes:

- Question 10: Does one who accepts the kshay of a parva tithi observe the parva on the parva tithi or a non-parva tithi?

- Answer: One who accepts kshay observes it on the preceding non-parva tithi. The scripture states that worship is to be performed on parva tithis, not on non-parva tithis. The principle of observing the preceding tithi during kshay is a well-established tradition.

- Observation of Samvatsarik Parva (Annual Festival):

- Question 11: When should the Samvatsarik Parva be observed?

- Answer: The Kalpa Sutra's commentary states that Lord Mahavir observed the Varshavas (rainy season retreat and observance) after 21 days of the rainy season. Following this tradition, the Samvatsarik Parva is observed after 21 days of the rainy season.

- Question 12: If the fifth day of Bhadrapad Shukla has kshay in a conventional calendar, when should the Samvatsarik Parva be observed?

- Answer: According to the Takhatgachh Samachari, if there is kshay of the fourth day, the kshay of the preceding tithi should be observed. However, considering "Lokaviruddha" (against common practice), the third and fourth days are combined, and the Samvatsarik Parva is observed one day before the celestial fifth day.

- Question 13: If Chandrashu Chandu Panchang shows two fifth days of Bhadrapad Shukla, on which tithi should the Samvatsarik Parva be observed?

- Answer: The Chaturvinshati Prabandh by Acharya Rajshekhar Surishwarji mentions that King Shalivahan observed Paryushan one day before the usual time as per Acharya Kaliksurishwarji. This supports observing the Samvatsarik Parva one day before the celestial fifth day.

- The Conflict with Laukik Panchangs and the Concept of "Aagamyanusari":

- The book repeatedly emphasizes that Jain principles dictate observing rituals on the parva tithi itself. When there's a kshay or vruddhi in a conventional calendar, the principle is to substitute the parva tithi on a non-parva tithi according to specific rules derived from Jain scriptures and tradition. This is to maintain the sanctity and sequence of the parva.

- The text strongly criticizes the practice of accepting vruddhi of parva tithis as per conventional calendars, calling it "Utsutra Prarupana" (incorrect propagation) and a deviation from Jinavachan (teachings of the Jinas).

- It highlights the importance of following Agam (scriptures) and the tradition of Gitanth (learned and virtuous monks).

- The book cites various scriptures and commentaries to support its arguments, including Bhagavati Sutra, Surya Prajnapti, Kalpa Sutra, Vyavahar Bhashya, and works by Acharyas like Umashvati, Shilanka, and Hemchandrasuri.

- Significance of Tithi Discussion:

- Question 14: Why do learned monks engage in such detailed discussions about tithis?

- Answer: Because the correct observation of parva tithis is crucial for self-welfare and spiritual progress. Performing religious acts on these specific tithis is emphasized as highly meritorious for accumulating good karma and longevity.

4. Muhpatti Bandhan Nibandh (Essay on Wearing a Muhpatti):

- This section focuses on the practice of wearing a muhpatti (mouth covering) by monks and nuns.

- Ancient Tradition: The practice is described as an ancient and fundamental Gitanth Parampara (tradition of the learned).

- Reasons for Wearing Muhpatti:

- Ahimsa (Non-violence): To protect minute organisms (Trasa Jiva) and air-bodied organisms (Vayu Kaya) from being harmed by breath or saliva during religious discourse or scripture reading.

- Protection of Scriptures: To prevent saliva from falling on holy scriptures, thus avoiding "Shruta Gyan Aashatna" (dishonoring knowledge).

- Scriptural Basis:

- The text refers to mentions of muhpatti in scriptures like Pravachan Pariksha and Upadesha Prasaad.

- It is stated that even Ganadhar Bhagwan (disciples of Lord Mahavir) wore muhpatti during religious discourses.

- The muhpatti was to be worn during lectures and scripture reading, not continuously like some modern practitioners.

- The method of wearing it was to insert it into the ear holes, not to tie it with strings.

- Various texts and commentaries are cited to support the proper method of wearing and the reasons behind it.

- Comparison with Other Religions: The practice is also compared to similar customs in other religions like Parsis, Muslims, and Vaishnavas who use veils or cloths for reverence during religious readings.

- Historical Evolution of the Practice:

- The practice was followed continuously until around Samvat 1912 (1856 CE).

- A dispute arose within the Shvetambar tradition when some monks, like Shri Buterayji Maharaj, who came from the Sthanakvasi sect, altered the practice.

- A letter from Acharya Shri Vijayanandsurishwarji (Atmaramji) to Munishri Alamchandji of Surat is included, where the Acharya acknowledges the tradition of wearing muhpatti but explains his inability to follow it due to his background, while encouraging his disciple to continue the practice.

- Arguments Against Continuous Wearing: The text clarifies that wearing muhpatti continuously is against scriptures, as it is meant for specific occasions like religious discourse.

- Significance of the Practice: The practice is emphasized as a way to uphold Ahimsa and protect Shruta Gyan, which are fundamental pillars of Jainism.

5. Digambar Perspective and Criticism (Pages 46-52):

- The book includes a section discussing the Digambar viewpoint, particularly regarding the "loss" of scriptures and their adherence to nudity.

- Scripture Loss: The Digambars' claim that their scriptures were "lost" or disconnected is challenged. The text argues that even if parts were lost, the core teachings and knowledge persisted until much later centuries.

- Nudity and its Consequences: The strict adherence to nudity by Digambars is criticized for leading to several issues:

- Inability for women to attain liberation.

- Restrictions on carrying vessels for food.

- The denial of food for Kevali Bhagwan (omniscient beings).

- Overall, a denial of the Chaturvidh Sangh (four-fold monastic order), as women cannot be nuns.

- Influence of Brahmanism: The book suggests that some Digambar practices might have been influenced by Brahmanical traditions due to their separation from Shvetambar scholars and literature.

- Adverse Effects of Nudity: The text lists practical disadvantages of nudity, including societal disapproval, obstruction in propagation, fear among children, government restrictions, and difficulties in begging for food, which can lead to defects like Adhakarmik and Audeshik.

6. Concluding Remarks:

- The book concludes with a prayer and a quote encouraging self-reflection and detachment from external concerns.

- It reiterates the importance of adhering to the traditions and scriptures passed down by learned saints and Acharyas, particularly in the current era of decline (Dusham Kal).

In essence, the book is a defense and clarification of traditional Jain practices concerning the calendar and monastic conduct, presented with scriptural evidence and historical context. It aims to guide followers in correctly observing religious dates and upholding the sanctity of scriptures and the principles of non-violence. The critique of the Digambar perspective serves to further emphasize the validity and reasoning behind the Shvetambar traditions.