Parmatmaprakash

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

This is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Parmatmaprakash" (also known as "Paramappapayas") by Yogindudev, based on the provided text:

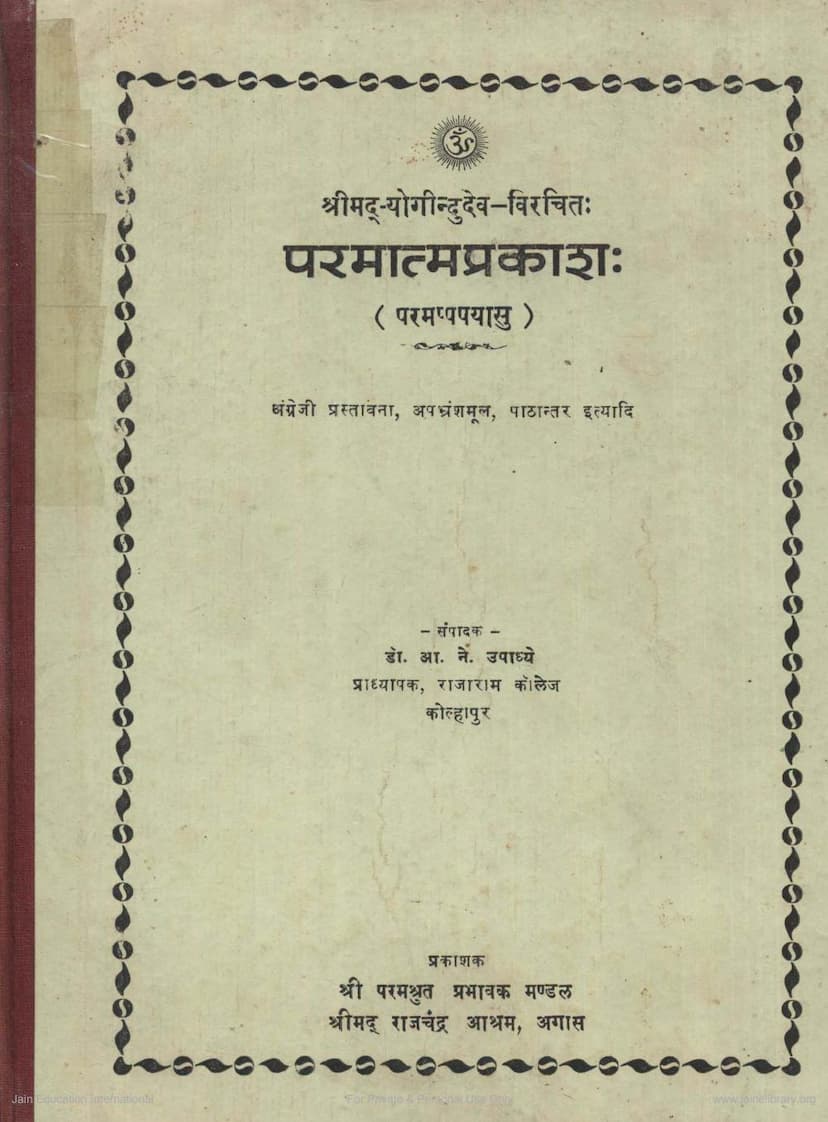

Book Title: Parmatmaprakash (Paramappapayas) Author: Yogindudev Publisher: Shri Paramshruta Prabhavak Mandal, Shrimad Rajchandra Ashram, Agas Editor: Dr. Adinath Neminath Upadhye Publication Year: Vikram Samvat 2044 (1988 AD)

Overview:

Parmatmaprakash (PP) is a highly popular philosophical and mystical work within Jainism, particularly among the Digambara tradition, although its teachings are considered universal. Composed in the Apabhramśa language, a precursor to modern North Indian languages like Hindi and Gujarati, the text is renowned for its accessible style and profound spiritual insights. It aims to guide the reader, and specifically the disciple Bhatta Prabhakara, towards understanding and realizing the nature of the Ātman (soul) and the ultimate state of Paramātman (Supreme Soul or Liberation).

Key Themes and Content:

-

Salutations and Introduction: The work begins with salutations to the Supreme Soul (Paramātman) and the liberated souls (Siddhas), acknowledging their stainless, knowledge-filled, and blissful nature. It also pays homage to the great Jinas and the five Paramagurus (Preceptors, Teachers, Monks). The author, Yogindu, states that the work is composed for Bhatta Prabhakara, who has suffered immensely in the cycle of birth and death (Samsara) and seeks liberation. (Dohas 1-10)

-

The Nature of Ātman: Yogindu outlines three aspects of the Ātman:

- Bahirātmā (External Soul): Identification of the self with the body and worldly attachments. This is considered ignorance.

- Antarātmā (Internal Soul): Realizing the self as distinct from the body, as an embodiment of knowledge, and engaging in deep meditation.

- Paramātmā (Supreme Soul): The ultimate state of self-realization, free from Karmas, pure, blissful, and omniscient. (Dohas 11-15)

-

Characteristics of Paramātman: Paramātman is described as eternal, stainless, blissful, the embodiment of knowledge, peace, and happiness. It is beyond the senses, Vedas, and scriptures. It has no beginning or end, no birth or death, no passions like anger, greed, or pride. It is neither subject to merit or demerit, nor joy or grief. It is Niranjana (unstained) and beyond all physical attributes like color, smell, taste, sound, or touch. It is the ultimate divinity, the subject of pure meditation. (Dohas 16-25)

-

The Soul (Jiva) and its Journey: The soul, though dwelling within the body, is fundamentally different from it. The body is considered ephemeral and an instrument of Karma. The soul's journey through Samsara is driven by Karma. Realizing the self as distinct from the body and its pleasures and pains is crucial for liberation. (Dohas 26-37)

-

Karma and its Effects: Karma is depicted as subtle matter that attaches to the soul due to passions and sense-pleasures, obscuring its true nature. There are eight types of Karmas that bind the soul. However, through meditation and equanimity, the soul can shed these Karmic coverings. (Dohas 48-65)

-

Differentiating Reality (Niscaya) and Convention (Vyavahara): The text emphasizes the importance of distinguishing between the ultimate reality (Niscaya Naya) and conventional reality (Vyavahara Naya). While conventional reality describes the soul's experiences within Samsara, the ultimate reality is the soul's pure, liberated self. (I. 46, II. 11-14)

-

The Three Jewels (Ratnatraya): Right Faith (Samyagdarśana), Right Knowledge (Samyagjñāna), and Right Conduct (Samyagchāritra) are presented as the path to liberation. These are not external practices but the inherent qualities of the realized soul. Realizing the self is the ultimate essence of these three jewels. (II. 11-14, 31-33)

-

Great Meditation (Parama-samadhi): The text highly esteems "Great Meditation" as the means to eliminate mental distractions, achieve equanimity, and realize the Paramātman. This state transcends worldly pleasures and pains, and it is through this profound meditation that the soul is freed from Karmas and attains liberation. (I. 14, 42, II. 38, 100, 165-172, 189-191)

-

Critique of Worldly Attachments: The work repeatedly warns against attachment to the body, family, wealth, sense-pleasures, and even external religious practices (like mere rituals, visiting holy places, or worshipping idols without inner realization) if they do not lead to self-knowledge. These attachments are seen as hindrances to liberation. (Various Dohas, e.g., I. 32, I. 83, II. 112, II. 130-138, II. 140-141, II. 144-145, II. 172, II. 182, II. 208, II. 210-211)

-

Importance of Knowledge: Knowledge (Jñāna), particularly self-knowledge, is paramount for liberation. Without it, scriptures and austerities are futile. Realizing the self leads to knowing the entire universe. (I. 103, II. 73-78)

-

Nature of Jainism: The text highlights the Jaina emphasis on the soul's inherent purity, the concept of infinite souls (each capable of becoming Paramātman), the importance of Ahimsa (non-violence), and an analytical approach to reality through Nayas. It also touches upon the classification of substances (Dravyas) within Jain metaphysics. (II. 15-28, II. 96-98)

-

Evaluation of Merits (Punya) and Demerits (Papa): Both Punya and Papa are considered binding to Samsara. While Papa leads to lower births and Punya to heavenly realms, both are ultimately obstacles to liberation. True liberation comes from transcending both, by destroying Karmas through right knowledge and meditation. (II. 56-57, II. 60-63, II. 71)

Author and Textual History:

- Author: Yogindudev (also referred to as Joindu, Jogindu, Yogindra, Jogicandra). The introduction provides a detailed discussion on the correct name and the influence of earlier Jain masters like Kundakunda and Pujyapada on Yogindu's thought.

- Date: Based on the analysis of quotations and textual influences, Yogindu is tentatively placed in the 6th century AD, or at least before Hemacandra (12th century AD) and Devasena (10th century AD).

- Commentaries: The text has been popular enough to attract commentaries in Sanskrit (by Brahmadeva), and Kannada (by Maladhare Balacandra and others). The editor, Dr. A.N. Upadhye, extensively discusses these commentaries and the various manuscripts studied, highlighting the textual variations and the challenges in establishing a definitive original text.

- Dialect: The work is written in Apabhramśa, which is characterized by phonetic fluidity, new metrical forms (especially Dohā), and a tendency towards simplification and popularization of language.

Significance:

Parmatmaprakash is considered a foundational text in Jain mystical literature. It offers a blend of philosophical exposition and practical guidance for spiritual aspirants, emphasizing self-effort, meditation, and the realization of the soul's inherent divine nature. Its accessibility in Apabhramśa and its coherent presentation of Jain doctrine and mysticism have contributed to its enduring popularity. The editor's detailed introduction and critical apparatus provide valuable insights into the text's history, its author, and its place within the broader spectrum of Indian philosophical and mystical traditions.