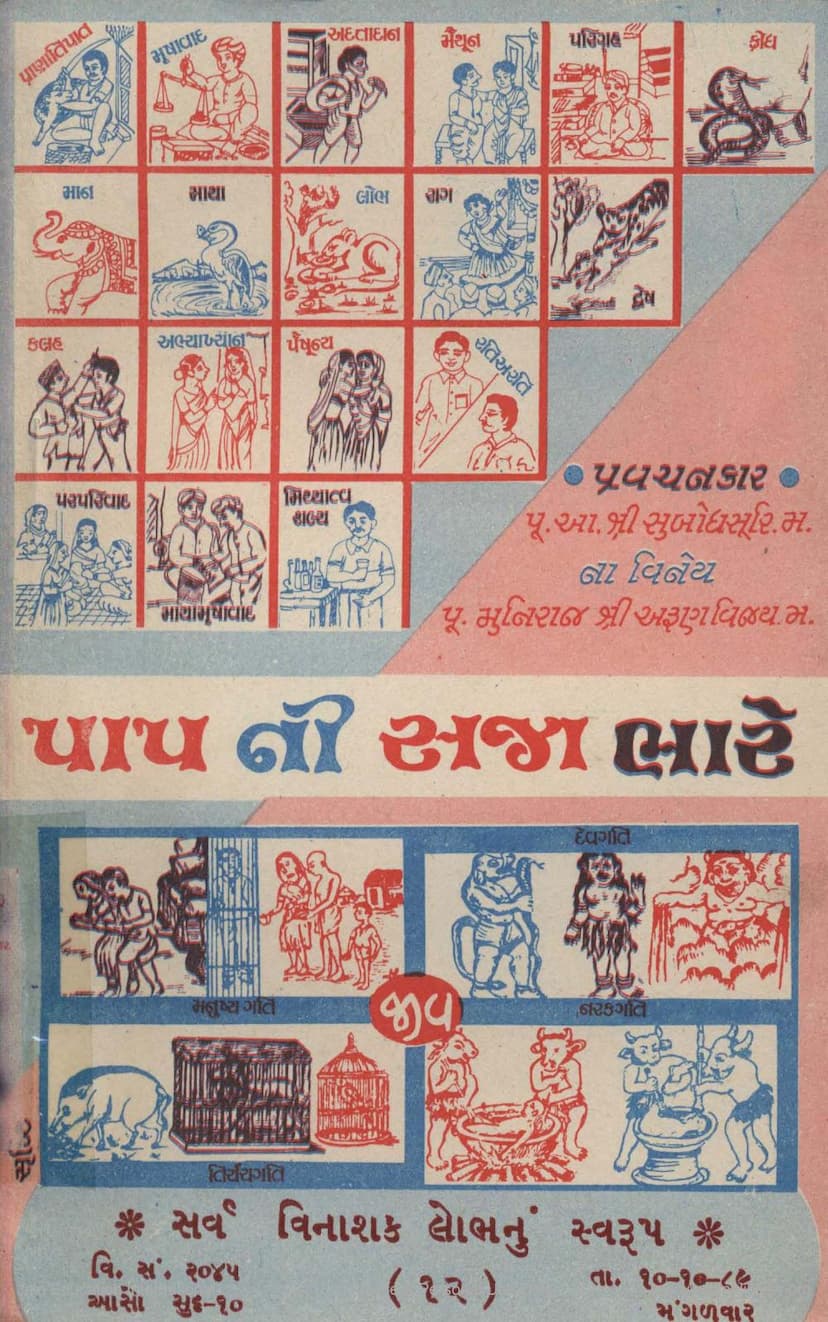

Papni Saja Bhare Part 12

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Papni Saja Bhare Part 12" by Arunvijaymuni, focusing on the theme of "Lobh" (Greed):

The text is the 12th lecture in a series titled "Papni Saja Bhare" (The Punishment of Sins), authored by Muni Arunvijay. The central theme of this particular lecture is Lobh (Greed), identified as the ninth of the eighteen principal sins in Jainism.

The lecture begins by referencing the Sutrakritanga Sutra, which identifies Krodh (Anger), Maan (Pride), Maya (Deceit), and Lobh (Greed) as the four severe inner faults that bind the soul. The text emphasizes that these kashayas (passions) are the root cause of suffering and the cycle of rebirth. It highlights that only liberated souls (Arhants and Siddhas) are completely free from these kashayas.

The author then delves into the nature of Lobh, explaining its pervasive presence in all living beings across different life forms and realms. While anger is dominant in hellish beings, pride in humans, and deceit in animals, greed is identified as particularly prevalent among celestial beings and in the worldly existence of all beings.

A key argument presented is that Lobh is the most destructive of the four kashayas. While anger, pride, and deceit might destroy specific qualities, greed destroys all virtues. It is described as a slow, cold poison that, though not immediately visible, has a potent and destructive effect. The text argues that from the progression of kashayas, Lobh is the most detrimental, as it encompasses and fuels the other three. It states that it is nearly impossible to find a being in the cycle of existence who is completely free from greed.

The lecture explores the intricate relationship between Lobh and Moh (attachment/delusion). It poses the question of which arises first, like the "chicken and egg" dilemma. The conclusion is that they are mutually reinforcing, creating a continuous cycle where greed leads to attachment, and attachment leads to greed, much like a well's rope turning a wheel. Moh is identified as the root cause from which Lobh arises, and Lobh, in turn, strengthens Moh.

The text emphasizes that Lobh is the cause of all destruction. It leads to broken relationships (preeti, prem-sambandh), loss of humility (vinay-namrata), lack of straightforwardness (rūjuta), destruction of friendships, and the annihilation of numerous other virtues. An example is given of an uncle who deceives his nephew with inflated prices, illustrating how greed undermines trust and relationships.

The author further elaborates on why Lobh is considered "sarva vinashak" (all-destroying). It is the foundation of all animosities, conflicts, and theft. It is the royal road to all vices like adultery, gambling, drinking, hunting, consumption of meat and fish, and visiting prostitutes. Greed leads individuals away from their own well-being and pulls them towards destructive paths.

The lecture recounts the famous story of ** Muni Ashadhbhuti**, who fell from grace due to his intense greed for Laddus (a sweet). Despite being a Muni, his desire for the Laddus led him to repeatedly change his form to obtain them, ultimately resulting in his downfall and living as a householder for twelve years. His eventual liberation occurred through deep repentance and spiritual practice, demonstrating the potential for redemption even after succumbing to greed.

The text highlights the difficulty of overcoming Lobh, even for ascetics who undertake severe austeries like fasting for months or chanting mantras for hours. The temptation of wealth (Kanchan) can even lead astray renunciates. The author points out that abandoning external attachments is easier than conquering the internal greed residing in the mind.

The lecture then discusses Lobh in the context of the 14 Guṇasthānas (spiritual stages) in Jainism. It explains how even at the 10th Guṇasthāna (Sukshma-Samparyayi), where only subtle greed remains, a slight resurgence of this greed can lead to a fall. This illustrates the immense power of even subtle forms of greed.

The author uses the analogy of a snake and ladder game to describe the soul's journey through the Guṇasthānas, where progress is made by overcoming karmas, but a fall can occur due to the resurgence of kashayas like greed. The subtle greed, even in the form of desiring a comfortable resting place or fresh air, is still a form of greed that can hinder spiritual progress.

The text further explains the concept of Lobh and Labh (profit/gain) as a vicious cycle. As profit increases, so does greed, and as greed increases, so does the desire for more profit. This is illustrated with the example of gambling, where initial wins fuel greed, leading to greater losses and addiction. Gambling is presented as a gateway to many other sins like theft, deceit, and substance abuse.

The lecture criticizes the prevalence of lotteries as a modern form of gambling, which exploits people's greed. It highlights how governments and businesses leverage this weakness for profit, demonstrating that while material possessions are transient, human desire and greed are persistent.

The text emphasizes that desire (Iccha) is the root of greed. It compares desire to the infinite sky, having no end or direction. When this desire is directed towards material, perishable objects, it leads to a cycle of dissatisfaction. Instead, channeling this desire towards the imperishable self (Ātma) can lead to eternal contentment.

The lecture then presents a vivid depiction of Lobh through a poem that illustrates its destructive consequences, leading to suffering, downfall, conflict, and the torment of hellish realms.

The text also distinguishes between gross greed (sthul lobh), which is more easily identifiable and potentially easier to overcome, and subtle greed (sukshma lobh), which is more insidious and difficult to eradicate.

The author emphasizes that greed is the cause of all sins, including anger, lust, delusion, and hatred. It is the driving force behind repetitive cycles of suffering across the four realms of existence.

A story of a learned Pandit is narrated to illustrate how greed is indeed the "father of all sins." The Pandit, unable to answer his wife's question about the father of sin, seeks the answer from a prostitute. Through a series of events, the prostitute reveals that greed is the root cause of sin, as it clouds judgment and leads to immoral actions.

The lecture uses the analogy of a "raksasa" (demon) that devours virtues and a "valli" (vine) that fuels all vices. Greed, it states, obstructs all accomplishments and leads to ruin, even for virtuous individuals.

The parable of a hermit who becomes entangled in worldly possessions and responsibilities, starting with a cat and ending with farming, illustrates how greed can ensnare even those seeking spiritual liberation. The pursuit of one thing leads to the need for another, perpetuating a cycle of desire and attachment.

The text highlights the unending nature of desire, comparing it to the ever-increasing stages of wealth, power, and celestial status. Even celestial beings, Indra, desire higher positions, creating a perpetual cycle of ambition and conflict.

The story of Kapil Kevali is presented as an example of overcoming intense greed. Kapil, while contemplating the immense wealth he could ask for, realized the futility of such desires and the transient nature of material possessions, leading him to renunciation and liberation.

The lecture reiterates that giving up greed leads to liberation, while succumbing to it results in downfall. It states that greed fuels anger, lust, and delusion, ultimately leading to destruction.

The story of Gunachandra and Balachandra, two brothers who, driven by greed for hidden treasure, engage in fratricide, betrayal, and multiple rebirths in various forms (serpent, lion, pigs, human), powerfully illustrates the long-lasting and devastating consequences of greed across lifetimes. This narrative underscores how greed perpetuates karmic cycles and leads to immense suffering.

The author concludes by emphasizing the importance of detachment and contentment (santosh) as the antidote to greed. He highlights that renunciation is the path to true happiness and freedom from suffering. The examples of virtuous Shravakas like Bhima Kundaliya and Punshi Seth, who lived contentedly with modest earnings, are contrasted with the insatiable desires of the wealthy and powerful, which ultimately lead to ruin.

The lecture advocates for cultivating contentment as the greatest wealth, capable of overcoming the "ocean of greed." It draws parallels with the story of Rama and Sita, suggesting that if Sita had exercised contentment and restraint, the events of the Ramayana might not have unfolded.

The text concludes with a call to action, urging individuals to embrace contentment and renunciation, following the teachings of the Tirthankaras, particularly Lord Mahavir, who preached the path of detachment. It warns against the destructive path of indulgence and self-serving desires, citing the cautionary tale of Rajneesh as a modern example of the downfall that awaits those who prioritize worldly pleasures over spiritual truth. The ultimate message is that renunciation is the only way to true happiness and liberation.