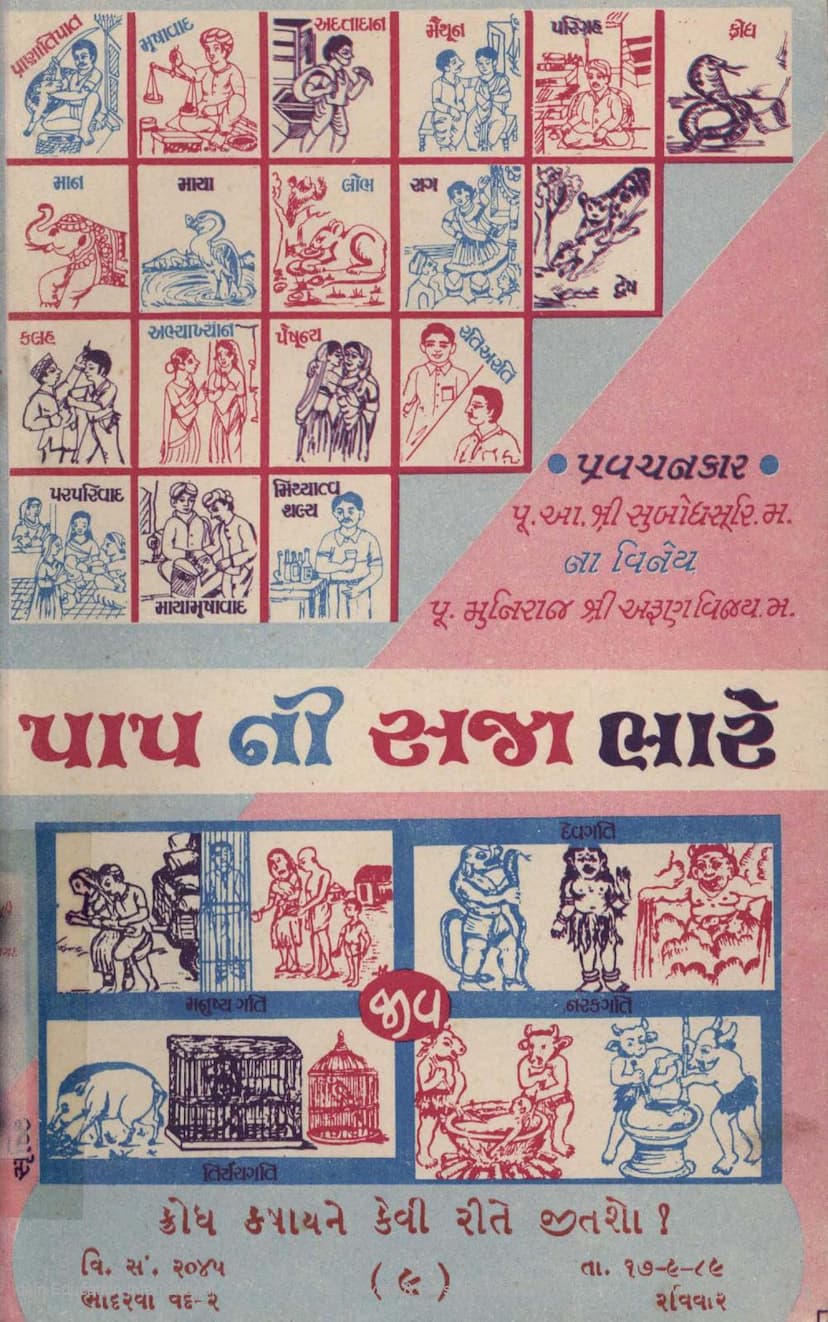

Papni Saja Bhare Part 09

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the provided Jain text, focusing on the content related to the virtue of anger (Krodh) and its place within the broader framework of Jain philosophy:

Book Title: Papni Saja Bhare Part 09 Author: Arunvijaymuni Publisher: Dharmanath Po He Jainnagar Swe Mu Jain Sangh Catalog Link: https://jainqq.org/explore/001494/1

This ninth part of "Papni Saja Bhare" (The Weight of Sins) focuses on the sixth papasthānak (place of sin), which is Krodh (Anger), and how to conquer it.

Core Concepts and Arguments:

- The Nature of Reality: The text begins by establishing the fundamental Jain understanding of the universe, comprising only two fundamental substances: Jeev (soul/living being) and Ajeev (non-living matter). The soul is characterized by consciousness and possesses eight inherent qualities, the third of which is "Infinite Conduct" or "Yathakhyat Swaroop" (true and proper state).

- The Soul's Impurity: The soul, in its worldly state, is considered impure due to innate attachment (raag) and aversion (dvesh). This impurity is likened to gold found in its raw ore, mixed with earth. This state of impurity is caused by karmic defilements, specifically the Mohaniya Karma (delusion-inducing karma), which generates attachment and possessiveness, clouding the soul's true nature.

- Mohaniya Karma and its Role: Mohaniya Karma is identified as the most potent of the eight karmas. It has two main categories: Darshan Mohaniya (perception-deluding karma) and Charitra Mohaniya (conduct-deluding karma). The Charitra Mohaniya karma includes Kashay Mohaniya, which encompasses the four primary passions: Krodh (Anger), Maan (Pride), Maya (Deceit), and Lobh (Greed). These four passions are considered the root cause of samsara (the cycle of birth and death).

- The Meaning of Kashay: The term kashay is explained etymologically as kash (samsara, cycle of birth and death) + aay (gain or profit). Thus, kashay signifies "gain of samsara," meaning the perpetuation and increase of the cycle of birth and death. The term is also metaphorically linked to kasai (butcher), implying that those who indulge in anger and other passions are like butchers, killing their own inner potential and perpetuating their suffering.

- Samsara as a Creation of the Soul: The text refutes the idea that God created the universe or samsara. Instead, it posits that each soul creates its own samsara through its raag and dvesh. The formula for samsara is given as Vishay (worldly desires/objects of senses) + Kashay (passions) = Samsara. This highlights the central role of passions in binding the soul to the cycle of existence.

- Kashay as Inner Sin (Bhav Paap): The text distinguishes between Dravya Paap (external/material sins) and Bhav Paap (internal/mental sins). Krodh, Maan, Maya, Lobh, Raag, Dvesh, Maya Mrushavada (deceitful speech), Mithyatva (false belief), and Shalya (spines/afflictions) are classified as internal or Bhav Paap. These are considered the real cause of karmic bondage, as they influence the bandha (bonding) of karma to the soul, affecting its duration and intensity.

- The Intensity of Karmic Bondage: The duration and intensity of karmic bondage are directly proportional to the intensity of kashay. Stronger kashay leads to longer karmic imprints and more severe suffering in future lives. Examples like Lord Mahavir's past karma affecting him in his final birth and the story of the 18th Vasudev illustrate how karmic consequences can span across numerous lifetimes.

- The Nature of Anger (Krodh): Anger is described as an internal enemy that arises consciously. It manifests physically with reddening eyes, trembling lips, increased body heat, altered voice, loss of control over words, and often leads to abusive language. It is a destructive force that can damage relationships, reputation, and even lead to physical and mental ailments like high blood pressure and brain hemorrhages.

- Krodh as a Destructive Force: Anger is compared to fire, consuming one's own essence before affecting others. It can ruin years of penance, spiritual practice, and virtuous conduct. The text provides examples of:

- Chandkoushik: A sage who, in a fit of anger, caused his own death and was reborn as a snake, eventually harming Lord Mahavir due to his past anger. This illustrates how unbridled anger can lead to multiple lifetimes of suffering.

- Acharya Chandrudracharya: A sage with a fiery temper whose disciples abandoned him. Even in his advanced state, his anger continued to cause harm, leading to his eventual realization and the attainment of omniscience through the patient endurance of his new disciple.

- Subhuma Chakravarti and Parashurama: Historical figures who, through their intense anger, caused widespread destruction and loss of life, ultimately leading to their own downfall and rebirth in hellish realms.

- The Four Types of Krodh: The text details the four types of anger based on their duration and karmic consequence:

- Anantanubandhi Krodh: Eternal anger, lasting a lifetime and extending into subsequent births. It binds one to the hellish realm and obstructs the attainment of true faith (samyaktva).

- Apratyakhyaniya Krodh: Anger lasting up to a year. If not atoned for through yearly rituals (samvatsarik pratikraman), it leads to rebirth in the animal realm. It hinders the practice of partial vows (deshvirati).

- Pratyakhyaniya Krodh: Anger lasting up to four months. If not resolved through repentance (chaturmasik pratikraman), it can escalate into the previous category. It obstructs the attainment of complete vows (sarvavirati).

- Sanjvalan Krodh: Anger lasting up to fifteen days (or even a moment). It can be overcome through regular repentance (paksik pratikraman) and leads to human or celestial births. It hinders the attainment of true equanimity (vitraagta).

- Conquering Anger: The primary means to conquer anger is through Samta (equanimity) and Kshama (forgiveness). The text emphasizes understanding that others act based on their own karmic states and limitations. The analogy of the rabbit's horns is used to illustrate that one cannot give what they do not possess, implying that abusive words come from a place of inner deficiency. Cultivating tolerance, understanding the karmic consequences of anger, and practicing repentance are crucial.

- The Decline of Virtues in the Current Era: The text laments the decline of virtues like patience, forgiveness, and simplicity in the current age, where materialism, external show, and monetary success are prioritized over inner qualities. This societal shift contributes to the prevalence of anger and other passions.

- The Importance of Repentance and Equanimity: Ultimately, the text highlights that even after committing grave errors fueled by anger, the path to liberation lies in repentance, seeking forgiveness, and cultivating equanimity. The example of Kurgadu Muni, who achieved omniscience by accepting the spat-out phlegm of angry monks with equanimity, demonstrates the transformative power of these virtues.

In essence, this text serves as a profound discourse on the destructive nature of anger within the Jain philosophical framework, tracing its roots to karmic impurities and its consequences across lifetimes. It advocates for the cultivation of equanimity, forgiveness, and constant self-awareness to overcome this potent passion and achieve spiritual liberation.