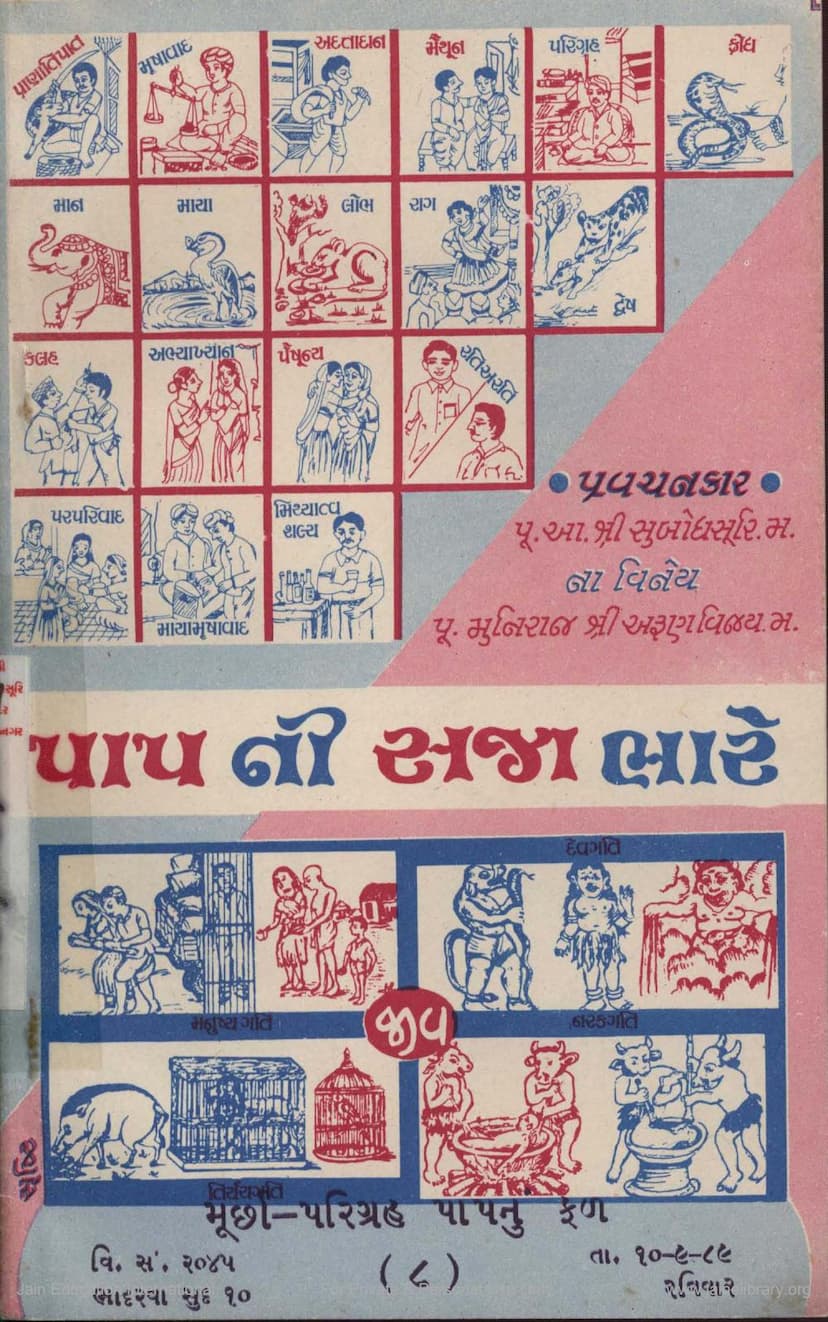

Papni Saja Bhare Part 08

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Loading image...

Summary

This comprehensive summary details the Jain text "Papni Saja Bhare Part 08" by Muni Arunvijay, focusing on the fifth transgression, Parigraha (Possession/Attachment), and its fruits. The text elaborates on the Jain philosophy concerning attachment to material possessions and its detrimental effects on the soul's journey towards liberation.

Key Themes and Concepts:

- The True Nature of Parigraha: The text clarifies that Parigraha is not merely the act of possessing objects but the deep-seated Murchha (attachment, affection, excessive fondness) towards them. Lord Mahavir emphasized that true possession lies in this mental attachment, not in the physical ownership of things.

- The Universe of Soul and Non-Soul: The fundamental constituents of the universe are defined as Jiva (soul) and Ajiva (non-soul/matter). Souls are sentient, conscious, and capable of experiencing pleasure and pain, while non-souls are inert, unconscious, and devoid of feelings. All experiences, both pleasant and painful, are borne by the soul, not by matter itself.

- The Cycle of Matter and Transformation: The text explains the constant process of transformation and re-combination of Pudgala (matter) at the atomic level. Matter is eternal but constantly changes form, undergoing cycles of creation and destruction. The soul, through its actions, utilizes and interacts with this matter, but matter itself remains indifferent and unchanged in its fundamental nature.

- The Soul's Unending Quest and Discontent: Despite experiencing an infinite number of material forms and objects throughout countless lifetimes, the soul remains perpetually dissatisfied. This dissatisfaction stems from the soul's inherent nature and its cycle of karma.

- The Root Cause of Attachment: The text identifies Rag (attachment) and Dvesh (aversion) as the primary drivers behind the soul's attachment to material possessions. Because the soul is sentient and experiences pleasure and pain, it develops these emotions towards objects that bring pleasure (leading to Rag) and those that bring discomfort (leading to Dvesh).

- The Futility of Material Possessions: The text uses vivid analogies to illustrate the ephemeral and ultimately unsatisfying nature of material wealth. Like food that turns into waste, or a beautiful house that eventually decays, material possessions offer only temporary satisfaction and are ultimately subject to destruction.

- The Dangers of Attachment: The accumulation and attachment to material possessions are presented as the root cause of suffering, leading to negative karmic consequences, including rebirth in lower realms like hell. The text emphasizes that while physical bodies and objects perish, the karmic imprints of attachment and aversion remain with the soul.

- The Self-Inflicted Bondage: The text powerfully argues that the soul is the architect of its own suffering through the constant chant of "I" and "mine" (Aham Mam). This unwavering sense of ownership and possessiveness towards transient material objects creates a cycle of attachment and further entanglement in the material world.

- The Twofold Nature of Parigraha: The text distinguishes between two forms of Parigraha:

- Dravya Parigraha (External Possession): This refers to the attachment to external, material objects, both animate (Sachitta) and inanimate (Achitta). This includes wealth, grains, land, houses, gold, silver, animals, and even dependents. The text lists nine principal categories of external possessions and further elaborates on their various sub-types as described in Jain scriptures.

- Bhava Parigraha (Internal Possession): This is considered the more insidious form of attachment, residing within the soul. It encompasses the four Kashayas (anger, pride, deceit, greed), Nokashayas (minor passions like laughter, fear, etc.), Mithyatva (false belief), and other internal states like lust, desire for fame, and ambition. The text emphasizes that attachment to these internal states is even more detrimental than attachment to external objects.

- The True Meaning of Renunciation: The text highlights that true renunciation (Aparigraha) is not merely the absence of possessions but the absence of Murchha (attachment) towards them. Even possessing essential items like clothes or a begging bowl (Patra) is permissible for ascetics if there is no attachment, desire, or fondness for them. The focus is on the internal state of detachment.

- The Impact of Attachment on Karma and Rebirth: The text explains how excessive attachment to material things (Alpaarambha Parigraha) leads to the binding of karmas that cause rebirth in lower realms like hell. Conversely, a simple life with minimal possessions and attachments (Alpaarambha Parigraha) leads to favorable rebirths, such as in the human realm.

- The Role of Contentment: Contentment (Santosh) is presented as the antidote to the cycle of desire and attachment. The text stresses that true happiness and liberation come from finding satisfaction within oneself, rather than pursuing external material gains.

- The Four Types of Souls Based on Possession and Attachment: The text categorizes souls based on the presence or absence of both objects and attachment:

- Souls with objects but no attachment (e.g., enlightened beings like Shali Bhadra).

- Souls with attachment but no objects (e.g., beggars with intense desires).

- Souls with both attachment and objects (e.g., materialistic individuals like Maman Seth).

- Souls with neither attachment nor objects (e.g., liberated souls).

- The Importance of Detachment and Right Conduct: The text provides cautionary tales and examples of individuals whose excessive attachment to wealth or possessions led to their downfall, including rebirth in hellish realms. It emphasizes that true wealth lies in inner spiritual development, not in material accumulation.

- The Four Pillars of Dharma for Overcoming Attachment: The text highlights the four cardinal virtues of Jainism – Dana (charity), Sheela (virtuous conduct), Tapa (austerity), and Bhava Dharma (inner devotion) – as the means to overcome the root causes of attachment and desire.

- The Distinction Between Adhikaran and Upakaran: For ascetics, the text distinguishes between Adhikaran (objects that cause harm or increase worldly entanglement, like weapons or excessive wealth) and Upakaran (essential objects that aid in spiritual practice, like religious texts or a begging bowl). Ascetics must renounce Adhikaran while cautiously utilizing Upakaran with detachment.

- The Interplay of Attachment and Violence: The text establishes a direct link between attachment (Parigraha) and violence (Himsa), particularly through the concept of Arambha (initiation of actions) and Samarambha (continuation of actions) driven by desire. This leads to a cycle of violence for acquiring and protecting possessions, ultimately contributing to the accumulation of negative karma.

In essence, "Papni Saja Bhare Part 08" serves as a profound discourse on the pervasive nature of attachment and the necessity of cultivating detachment, contentment, and spiritual understanding to break free from the cycle of suffering and achieve liberation, the ultimate goal in Jainism.