Padileha

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Padileha" by Dr. Ramanlal C. Shah, based on the provided pages:

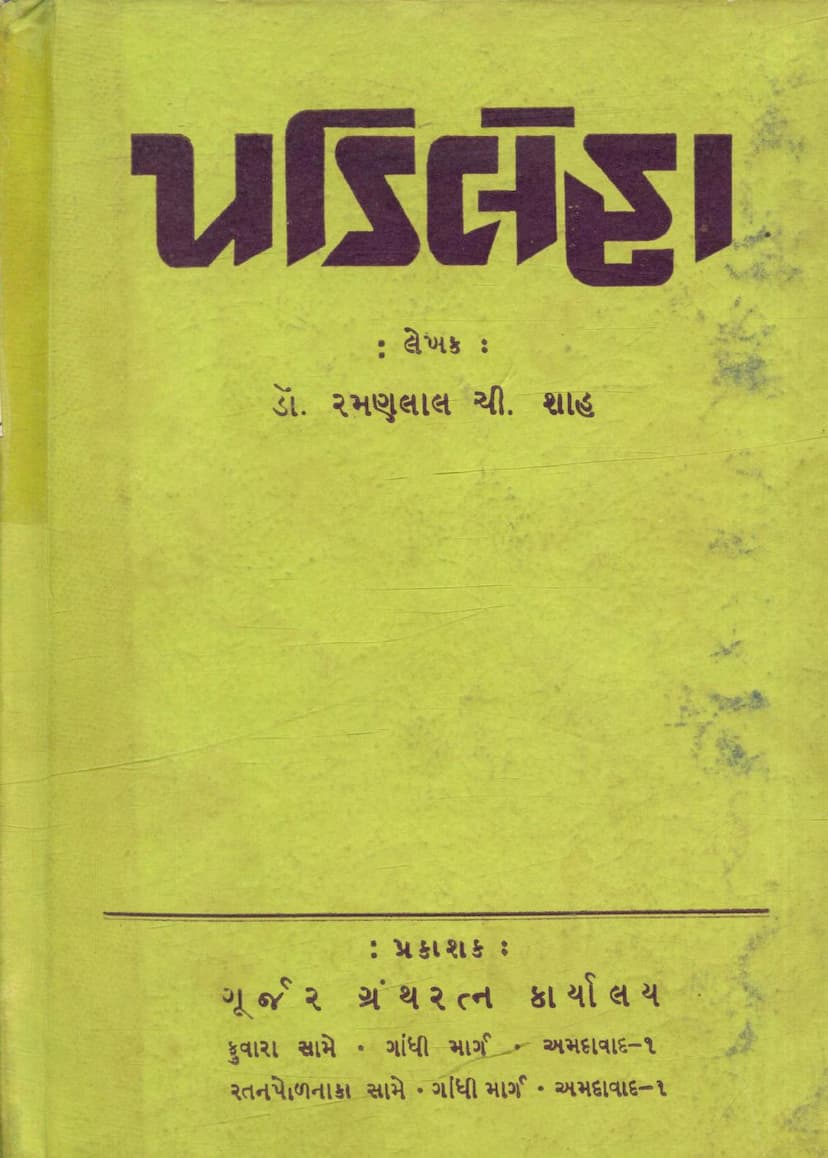

Book Title: Padileha Author: Dr. Ramanlal C. Shah Publisher: Gurjar Granthratna Karyalay Catalog Link: https://jainqq.org/explore/023286/1

Overview: "Padileha" is a collection of critical and research-oriented articles by Dr. Ramanlal C. Shah, who was the Head of the Gujarati Department at Mumbai University. Published in January 1979 by Gurjar Granthratna Karyalay, Ahmedabad, the book comprises scholarly discussions on various aspects of ancient and medieval literature, literature, and thought, with a particular focus on Jain literature and philosophy.

Meaning of "Padileha": The author explains that "Padileha" is a Prakrit word, meaning "Pratilekha" (प्रतिलेखा). It signifies a comprehensive, profound, and independent study conducted with meticulous attention and repeated, thorough observation. "Padileh" or "Padilehan" (Pratilekha - Pratilekhana) is a technical term in Jainism, still prevalent, especially among Jain monks.

Contents and Themes: The book is a compilation of articles previously published in various journals and commemorative volumes, including "Parab," "Kavilok," "Forbes Quarterly," "Ruchi," "Jain Yug," "Shri Mahavir Jain Vidyalaya Vallabhsuri Smarak Granth," "Sahityakar Premanand," and "Gujarati Sahityane Itihas." Dr. Shah expresses gratitude to these publications and their editors for their permission to reprint the articles.

Key Articles and Topics Covered (Based on the Table of Contents):

-

Ancient Indian Debates (પ્રાચીન ભારતમાં વાદો): This extensive article delves into the concept of "Vada" (debate or discourse) in ancient India.

- Etymology and Meaning: The word "Vada" originates from the Sanskrit root "vidh" and carries meanings like conversation, discourse, speech, advice, principle, proposal, philosophical debate, disagreement, argument, accusation, and rivalry. It also signifies agreement, explanation, report, etc.

- Purpose of Debate: Debates sharpen intellect by presenting arguments, refuting opposing views, and defending one's own stance. Listening to and studying different debates enhances knowledge, understanding, and clarity of perspective. The formation of "purva paksha" (proposing party) and "uttara paksha" (responding party) leads to better subject understanding and revelation of truth, echoing the saying "Vare Vare Nayate Tattvam Naye!" (Truth is revealed through repeated inquiry!).

- Origin of Debates: Debates arise from the human endeavor to solve fundamental questions about existence, consciousness, the universe, morality, and the ultimate purpose of life. The author lists numerous questions pondered throughout history, such as the origin of life, the nature of the soul, the composition of the universe, the meaning of sin and virtue, and the path to liberation.

- Diverse Philosophical Schools: The article surveys a vast array of philosophical schools and viewpoints prevalent in ancient India, covering areas like religion, philosophy, grammar, logic, literature, science, astrology, and politics. Examples of "Vada" discussed include:

- Aphalvad: The doctrine that actions have no fruit.

- Akarakvad: The doctrine that the soul does not perform actions.

- Panchamahabhutavad: The belief that only the five great elements exist, and the soul is an emergent property of these elements.

- Tajeevatajareerivad: The theory that the soul is identical with the body and perishes with it.

- Aatma Shashthavad: The view that there are six souls (beyond the five elements).

- Kriyavad: The principle that actions have consequences.

- Ekantavad: The belief that the universe is fundamentally one, like clay manifesting in various forms.

- Drishtidharmanirvanvad: The idea that liberation can be attained in this life through the enjoyment of sensory pleasures.

- Shashvatvad: The doctrine of eternalism.

- Uddhata Madhanikvad: The view that the soul undergoes various states after death.

- Adhityasamutpanna-vad: The belief that the universe and soul arise without a cause.

- Broader List of Vadas: The author presents an extensive list of various philosophical schools and doctrines, including Ishwarvad, Atmavad, Ajnanvad, Purushvad, Kalvad, Swabhavvad, Yadrichchhavad, Jativid, Visheshvad, Kriyavad, Akriyavad, Shashvatvad, Ashashvatvad, Ekantavada, Anekantavada, Satkaryavad, Asatkaryavad, Astikvad, Nastikvad, Mayavad, Mithyavad, Karanvad, Krutvad, Niyativad, Avaktavyavad, Lokvad, Lokatikvad, Aphalvad, Sthitivad, Drishtivad, Drushtvad, Karmavad, Vinayavad, Vikshepvad, Vinashvad, Akarvad, Abhedvad, Bhrutvad, Panchamahabhutikvad, Charvakvad, Tajeevatajareerivad, Aatmathshthavad, Siddhivad, Sthanvad, Apohavad, Jnanvad, Daivatvad, Pratityasamutpadvad, Anatmavad, Kshanikvad, Sarvastivad, Shunyavad, Vibhayvad, Syadvada, Anekantavada, Kevaladvaitavad, Vishishtadvaitavad, Shuddadvaitavad, Dvaitadvaitavad, Prakrtivad, Prarabdhavad, Anyanyavad, Ajneyavad, Chaturyaamsanvarvad, Vidhivat, Nayavad, Chaityavad, Ganadharvad, Nidhavvad, Sthavirvad, Vijnanvad, Adhityasamutpanna-vad, Sukhadukhvad, Anandvad, Tatparyavad, Anumitivad, Rasvad, Dhvanivad, Abhidhavada, Deergh Abhidhavada, Lakshnavada, Alankaravad, Chamatkaravad, Abhihitanyayavad, Anvit Abhidhanavada, Phetvad, Ritivad, Chityavad, Vakrtivad, Guna-vad, Shabdarathavad, Akhandaivad, Dhatu-vad, etc.

- Intellectual Development: The sheer number of these "Vadas" indicates the high level of intellectual development in ancient India.

- Debating Practices: Ancient India had a practice of holding assemblies to determine the validity of opposing arguments. These assemblies were sometimes patronized by royalty, but their success depended on the impartiality of the king. Debates involved direct contests between proponents and opponents, and often, losing debaters would become disciples of the victors (e.g., Indrabhuti Gautama and his disciples becoming disciples of Lord Mahavir).

- Distinction between Debate and Vituperation: Honest debates for the sake of truth were beneficial, but when debates were driven by the desire to defeat others, they degenerated into "vitandavad" (vituperation) or "shushkavad" (dry debate).

- Caution Against Unwise Debates: The text cites the "Narada Bhakti Sutra" and "Sthananga Sutra" to highlight instances where debates were won through flattery of the chairman or intimidation of the opponent. It also mentions the persuasive tactics of certain philosophers in misleading ordinary religious people.

- Equanimity in Debate: The importance of engaging in debate with equals is stressed, citing the Rigveda's analogy of a horse competing with another horse, not a donkey. Engaging with superiors is discouraged to maintain respect and avoid conflict. Manu Smriti is quoted regarding avoiding arguments with elders, teachers, guests, dependents, children, the sick, physicians, relatives, and servants.

- Skill in Debate: The ability to argue one's case and refute opponents required high logical acumen and sharp intellect. Titles like "VadI" (debater), "Vadimal" (champion debater), "Vadivetala" (erudite debater), "Vadichandra," "Vadisinha," "Vadibhooshan," "Vadiraj," "Vadiswar," "Vadiendra" were conferred upon skilled debaters.

- Literary Debates: Many ancient texts were dedicated to presenting and refuting various "Vadas," showcasing the authors' unparalleled intellect and logical prowess.

- Categorization of Vadas: The text mentions that while independent texts on all "Vadas" are not available, scattered references in various scriptures provide information. It highlights the classification of 363 "Vadas" into four main categories: Kriyavad, Akriyavad, Ajnanvad, and Vinayavad, with detailed breakdowns.

- Specific Vadas Explained: The article elaborates on the core tenets of Kriyavad (action and its consequences), Akriyavad (denial of action's consequences, attributing events to God or nature), Ajnanvad (reliance on conventional practice, skepticism towards scriptures), and Vinayavad (emphasis on ethical conduct for liberation, potentially overlooking knowledge). It also touches upon the concept of "Areyavad" (evasive responses) used by those hesitant to commit to a definitive view.

- Folk Beliefs (Lokvad): Superstitious beliefs prevalent in ancient times were also categorized as "Lokvad."

- Impact of Debates: The existence of numerous "Vadas" reflects the deep intellectual engagement and philosophical inquiry prevalent in ancient India.

-

Kuvlayamala (कुवल्अमाला): This section focuses on the literary work "Kuvlayamala."

- Significance of Prakrit Literature: The author emphasizes the importance of Prakrit language and literature in Indian culture, preserved largely through Jain and Buddhist traditions. Jain monks and scholars maintained the continuity of Prakrit studies.

- Kuvlayamala's Place in Literature: "Kuvlayamala," a monumental work in Prakrit, is described as a treasure of Jain literature, comparable to or even surpassing Banabhatta's "Kadambari."

- Author and Time: Composed by Acharya Udyotan-suri, a disciple of Acharya Tattvacharya, in the 9th century Vikram Samvat (835 AD), "Kuvlayamala" is a significant contribution to Jain narrative literature.

- Reception and Influence: Despite its quality, "Kuvlayamala" did not achieve widespread study or commentary compared to other ancient Jain narrative works. However, references to it appear in later works like Nemichandrasuri's "Akhyanamanish" and Prudevasuri's commentary, indicating its influence.

- Praise by Hemachandracharya's Guru: Devachandrasuri, Guru of the renowned Hemachandracharya, praised the author of "Kuvlayamala" for his masterful storytelling.

- Debate with Siddharshi: An anecdote from "Prabhavakcharitra" suggests a rivalry between Udyotan-suri and Siddharshi, though the historical accuracy of this event is questioned due to the chronological order of their works.

- Sanskrit Adaptation: A Sanskrit summary of "Kuvlayamala" was created by Ratnaprabhasuri in the 14th century Vikram Samvat.

- Reasons for Limited Dissemination: The author suggests that the extensive narrative, linguistic complexity, depiction of erotic elements, or other factors might have contributed to its limited circulation.

- Author's Information: Udyotan-suri, according to his own account, provided details about his lineage and the location and time of composition, shedding light on his background and the historical context.

- Literary Style and Content: The work is characterized by its diverse literary techniques, including metaphors, elegant prose, dialogues, songs, and various poetic meters. It is described as a "Champukavya" (a mixed prose-verse composition) and is noted for its blend of religious teachings, philosophical discussions, and secular narratives.

- Description of Cities and Seasons: The text vividly describes various cities and meticulously depicts the seasons, using rich imagery and figurative language, particularly highlighting the descriptions of Vinita Nagari and the portrayal of seasons like Sharad, Varsha, and Vasant.

- Philosophical and Religious Content: The author integrates profound Jain philosophical concepts, such as the nature of the soul, karma, the cycle of rebirth, and the path to liberation, through the narrative. The detailed descriptions of Jain monks' daily routines, rituals, and studies of various scriptures are also noteworthy.

- Narrative Structure: The story unfolds with intricate weaving of the main plot and sub-plots, creating a captivating narrative flow that holds the reader's interest.

- Characterization: The narrative features a wide array of characters, including kings, queens, ascetics, Brahmins, merchants, scholars, deities, demons, and common folk, each contributing to the rich tapestry of the story.

- Narrative Variety: The plot encompasses diverse events such as battles, religious rituals, abductions, sacrifices, suicides, betrayals, journeys, shipwrecks, and supernatural encounters. The settings range from forests and cities to mountains, oceans, and celestial realms, providing a broad canvas for the narrative.

-

Hemachandracharya: His Life and Works (હેમચંદ્રાચાર્ય : એમનું જીવન અને કવન): This article focuses on the life and literary contributions of Hemachandracharya.

- Golden Age of Gujarat: The author highlights the Solanki era in Gujarat, marked by the reign of powerful kings like Mulraj, Bhim, Karna, Siddharaj, and Kumarpal, as a golden age of prosperity and culture.

- Hemachandracharya's Influence: Hemachandracharya, known as "Kalikal Sarvagnya" (Knower of all things in the current era), is credited with elevating this era to its peak and profoundly influencing the language, literature, and intellectual life of Gujarat. His absence would have left the period incomplete and shrouded in darkness.

- Biographical Sources and Legends: Information about Hemachandracharya comes from Sanskrit, Prakrit, and Apabhramsha texts, including works by Pradyumnasuri, Merutongacharya, Rajashekhar, and Jinamandan Upadhyay. The author notes the prevalence of legends surrounding Hemachandracharya, similar to those about Kalidasa, Banabhatta, Vikram, and Bhoj.

- Birth and Early Life: Born in Dhundhuka in 1045 AD, Hemachandracharya's parents were Chach and Pahini. His childhood name was Chang. A prophecy foretold his greatness at birth.

- Initiation and Education: At the age of nine, Chang was initiated into monastic life by Devachandrasuri, receiving the name Hemachandra. He underwent rigorous study of Sanskrit, Prakrit, and Apabhramsha, along with various other disciplines like grammar, rhetoric, yoga, logic, history, and philosophy.

- Ascension to Acharyaship: Despite his desire to study in Kashmir, his guru, Devachandrasuri, recognized his immense potential and established him as an Acharya at the young age of twenty-one in Khambhat in 1160 AD.

- Patronage by Siddharaja: Hemachandracharya gained the attention of King Siddharaja of Patan through a religious debate. Siddharaja, impressed by Hemachandracharya's intellect, appointed him to his court, replacing existing scholars.

- "Siddha-Hema" Grammar: Siddharaja commissioned Hemachandracharya to create a comprehensive grammar for Gujarat. Drawing from various grammatical traditions, Hemachandracharya produced "Siddha-Hema Shabdanushasan," a monumental work that became the standard grammar for Prakrit and Apabhramsha. Its manuscript was celebrated and distributed widely.

- Friendship and Influence: Hemachandracharya became a close friend and advisor to Siddharaja, influencing the king's inclination towards Jainism. He authored "Yashray Mahakavya," a historical epic about Siddharaja and his era. Their relationship extended to shared religious activities like visiting Jain temples and undertaking pilgrimages.

- Religious Tolerance: Hemachandracharya advocated for religious harmony, respecting all faiths and emphasizing the underlying unity of spiritual truths. He is noted for reciting prayers that acknowledge the divine aspects of various traditions.

- Relationship with Kumarpal: After Siddharaja's death, Kumarpal, his nephew, ascended the throne. Hemachandracharya had previously saved Kumarpal's life. Kumarpal, influenced by Hemachandracharya, implemented ethical reforms in his kingdom, including the prohibition of animal sacrifice, gambling, hunting, and the consumption of meat and alcohol. He also promoted Jainism and sponsored the construction of numerous Jain temples.

- Later Works and Legacy: Towards the end of his life, Hemachandracharya composed works like "Yogashastra" to provide solace to Kumarpal, who faced the issue of succession. Hemachandracharya led a life of constant diligence, lived to a ripe old age of 84, and passed away in 1229 AD.

- Literary Contributions: Hemachandracharya's literary contributions span grammar, literature, poetics, and philosophy. His works are recognized globally, with German scholar Dr. Buhler being among the first to offer a comprehensive review of his life and literature. K.M. Munshi rightly recognized Hemachandracharya as Gujarat's greatest benefactor.

- Key Literary Works: His significant works include the grammar "Siddha-Hema Shabdanushasan," the epic "Yashray," "Tattvasutra," "Mahavir Charitra," "Purana," "Lingānushasan," "Chhandānushasan," "Kavyanushasan," "Anekarth Sangraha," "Abhidhan Chintamani," and "Deshi Nama Mala." His verses, often used as examples in grammar, are also celebrated for their poetic merit.

-

Tracing the So-Called Second Nal-Akhyan of Bhalan (ભાલણના કહેવાતા બીજા ‘નળાખ્યાન’નું પગેરું): This article critically examines the authorship and authenticity of a work attributed to the poet Bhalan.

- Discovery of a Second Nal-Akhyan: The editor of "Prachin Kavya Mala" first brought to light the existence of a second "Nal-Akhyan" by Bhalan, previously unknown to scholars.

- Reasons for Re-writing: The author of the second "Nal-Akhyan" states that his first version was lost or not returned, prompting him to rewrite it. The editor of "Prachin Kavya Mala" speculated that the first version might have been superior due to the initial creative fervor.

- Bhalan's Own Statement: The poet himself, at the end of the second "Nal-Akhyan," indicates its re-creation due to lost circumstances.

- Publication and Discrepancies: The second "Nal-Akhyan" was published in "Brihat Kavya Dohana" in 1895, with variations in text and some missing verses compared to the "Prachin Kavya Mala" version.

- Doubts Raised by Ramlal Modi: In 1924, the editor, the late Ramlal Modi, expressed doubts about the authenticity of the second "Nal-Akhyan" in his preface, citing several reasons and suggesting it might be a modern creation or falsely attributed to Bhalan.

- K.K. Shastri's Opinion: K.K. Shastri, in his "Kavi Charitra Part 1" (1938), initially supported Modi's doubts but later revised his opinion, suggesting the presence of medieval linguistic features. However, he did not provide new evidence beyond Modi's initial concerns.

- Critical Analysis of Authenticity: The author of "Padileha" undertakes a detailed comparative analysis of the two "Nal-Akhyans" based on internal and external evidence.

- Arguments Against Bhalan's Authorship: The core arguments presented against the second "Nal-Akhyan" being by Bhalan include:

- Lack of Shared Lines: Not a single line from Bhalan's known "Nal-Akhyan" appears in the second version, which is unusual for a poet rewriting their own work.

- Absence of Original Concepts: Bhalan's known work contains unique imaginative passages and influences from "Nalshadhiya Charita" that are entirely absent in the second version. Conversely, the second version contains concepts not found in Bhalan's known work.

- Linguistic and Stylistic Differences: Significant variations in language, style, and narrative detail are observed.

- Historical Inaccuracies: The second "Nal-Akhyan" contains factual inaccuracies regarding historical events and practices (e.g., monthly salaries in medieval times, or mixing the names of celestial beings).

- Inconsistent Depiction: The portrayal of characters and events often contradicts Bhalan's known style and understanding of the original Mahabharata narrative.

- Presence of Modernisms: The author suggests that the presence of certain phrases and the compilation of the final part of the second "Nal-Akhyan" might indicate modern interpolation or creation.

- Conclusion on Authorship: The author concludes that the second "Nal-Akhyan" is not by Bhalan but is likely a modern fabrication, possibly created by Chhotalal Narbheram Bhatt, who translated the Mahabharata into Gujarati in 1888, and used that translation as a primary source.

-

**Yashovijayji and His Jambuswami Ras (यशोविजविजयजी और </strong>