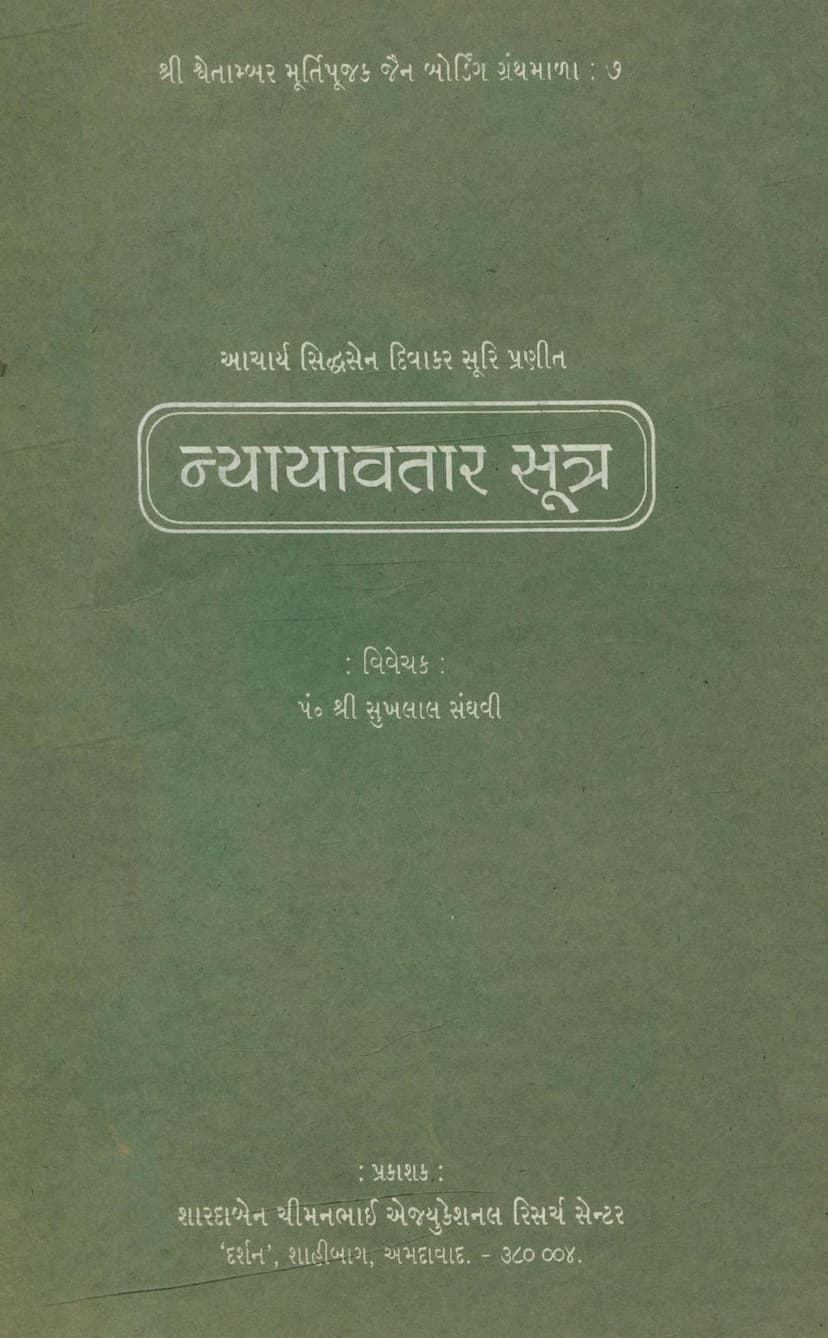

Nyayavatar Sutra

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Nyayavatar Sutra" by Acharya Siddhasena Divakara Suri, with commentary by Pandit Sukhlaal Sanghvi:

Overall Context and Significance:

The Nyayavatar Sutra is a foundational text in Jain logic and epistemology, attributed to the renowned Jain scholar Acharya Siddhasena Divakara. Despite its brevity (32 verses), it is considered a profound work that lays the groundwork for Jain reasoning and philosophical inquiry. The commentary by Pandit Sukhlaal Sanghvi provides a detailed analysis, placing the Nyayavatar within the broader context of Indian philosophical traditions, particularly comparing it with Buddhist logical works like Dignaga's Nyaya Pravesha and Dharmakirti's Nyaya Bindu. The republication of this work by the Shardaben Chimanbhai Educational Research Institute aims to make Sanghvi's insightful commentary accessible to a wider audience, filling a gap in Gujarati scholarship on this important text.

Key Themes and Arguments:

The Nyayavatar Sutra primarily focuses on the theory of pramana (means of valid knowledge). Pandit Sukhlaal Sanghvi's commentary delves into several crucial aspects:

-

Introduction to Nyayavatar and its Author:

- Acharya Siddhasena Divakara is a prominent Jain ācārya, with his works including Sanskrit Bātrīśis and the Prakrit Sammati Tark.

- There is scholarly debate regarding his exact period, with ancient Jain tradition placing him in the 1st century CE and modern scholars in the 5th century CE.

- Professor Jacobi theorized that Divakara was influenced by the Buddhist logician Dharmakirti and that Nyayavatar was an imitation of Nyaya Bindu, a claim Sanghvi refutes based on his analysis.

-

Comparison with Other Logical Texts:

- Sanghvi extensively compares Nyayavatar with Dignaga's Nyaya Pravesha and Dharmakirti's Nyaya Bindu. He finds similarities in form, language, and certain concepts but is unable to definitively establish the chronological order, even suggesting that Nyayavatar might precede the others in some respects.

- He praises Nyayavatar's clarity of language, precision of definitions, and the conciseness with which it explains complex logical concepts, suggesting it holds a position equal to, if not higher than, Nyaya Bindu in these aspects.

-

External Form (Language, Style, Naming):

- Language: While Sanskrit was becoming prevalent in philosophical discourse (Nagarjuna being an early adopter), Jain scholars like Umasvati also used Sanskrit alongside Prakrit. Siddhasena Divakara's use of both Sanskrit and Prakrit for his philosophical works is noted.

- Style: The text highlights the evolution of Indian philosophical literature through different eras (Sutra, Bhasya, Vartika, Tikā) and verse meters. Siddhasena's use of Anushtubh meter in Nyayavatar is compared to Samantabhadra's Aptamimamsa, drawing attention to its significance in Jain logical literature.

- Naming: The trend of naming philosophical works with suffixes like Vartika, Bindu, Samucchaya, and Mukha is observed, with Nyayavatar, Nyaya Pravesha, and Nyaya Bindu belonging to a similar naming convention, suggesting a possible tradition of influence or response among these works.

-

Internal Form (Content and Concepts):

- Primary Subject: The core subject is the enumeration of pramanas from a Jain perspective. It focuses on Pratyaksha (Direct Perception) and Paroksha (Indirect Knowledge), rather than the five types of Agamic knowledge or the four types of Pramanas found in other schools.

- Pramana Definitions: Sanghvi emphasizes the clarity and enduring relevance of the definitions of pramana in Nyayavatar. He notes that later Jain scholars, both Śvetāmbara and Digambara, largely adopted these definitions without significant alteration.

- Pratyaksha and Paroksha: The text defines Pratyaksha as knowledge that grasps an object directly and Paroksha as knowledge that grasps indirectly. The distinction is crucial for understanding the scope of knowledge.

- Inference (Anumana): Anumana is defined as knowledge that determines the sadhya (the to-be-proved) through a hetu (reason or middle term) that is invariably connected to it. Sanghvi highlights Siddhasena's defense of Anumana as non-erroneous (abhranta), countering Buddhist views that consider generalities (which are the basis of inference) as conventionally real but not ultimately true.

- The Nature of Valid Knowledge: The text grapples with the idea that all knowledge might be erroneous. Sanghvi clarifies that Pratyaksha is not inherently erroneous because its very nature is to reveal itself and its object. The validity of pramana depends on the existence of both the knower and the known.

- Word-Pramana (Shabda): The valid word (Shabda) is defined as a sentence that is free from contradiction, conveys the ultimate truth, and is received from a reliable source (Apta).

- Scripture (Shastra): A true Shastra is defined as originating from an omniscient being, being irrefutable, and guiding people away from erroneous paths.

- Per-Artha Pramana (Knowledge for others): The text distinguishes between knowledge for oneself (Sva-artha) and knowledge for others (Para-artha). While Anumana is clearly established as Para-artha, Siddhasena argues that Pratyaksha can also be considered Para-artha when communicated through speech, as the speech acts as a cause for the listener's perception. This challenges the Buddhist view that only inferential knowledge can be communicated effectively for others.

- The Role of the Paksha (Thesis): Siddhasena emphasizes the necessity of stating the paksha (the proposition to be proved) in argumentative discourse, arguing that its absence can lead to confusion and the misinterpretation of the hetu (reason). This is presented as a likely response to Buddhist logicians who might have considered the paksha less essential.

- The Use of Examples (Drishtanta): The text discusses the utility of examples in both sadharmya (similarity) and vaidharmya (dissimilarity). However, it also suggests that examples are not always necessary and can be redundant if the underlying relationship (vyapti) is already understood.

- Fallacies (Abhasa): The work elaborates on fallacies in reasoning, including Pakshabhasa (fallacies of the thesis), Hetvabhasa (fallacies of the reason), and Drishtantabhasa (fallacies of the example). Sanghvi provides detailed explanations and examples of these fallacies, drawing parallels with other logical traditions.

- Dushana and Dushanasabhasa (Rebuttal and False Rebuttal): The text distinguishes between exposing flaws in an opponent's argument (Dushana) and falsely accusing a valid argument of having flaws (Dushanasabhasa).

- Pramaṇa's Fruit: The ultimate fruit of pramana is the removal of ignorance. For the highest knowledge (Kevala Jnana), this includes bliss and equanimity, while for other forms of knowledge, it leads to the understanding of what to adopt and what to discard.

- Naya (Standpoints): A significant contribution of Jain logic is the concept of Naya, which refers to different standpoints or ways of looking at reality. Nyayavatar distinguishes between pramana's subject matter (reality in its entirety) and naya's subject matter (reality as viewed from a particular angle). Sanghvi explains how various Nayas (like Dravyarthika and Paryayarthika, Arthanaya and Shabdanaya) help in understanding the multifaceted nature of reality, ultimately leading to Syadvada.

- Syadvada: The text connects the concept of Nayas to Syadvada, the Jain doctrine of conditional predication, highlighting how multiple Nayas contribute to a comprehensive understanding of reality.

- The Nature of the Soul (Jiva): The soul is described as the knower (Pramata), self-luminous (Svanirbhasi), agent (Karta), experiencer (Bhokta), and distinct from physical elements. Its existence is established through self-awareness (Samsiddha).

- Universality of Pramanas: The system of knowledge and its means is presented as eternal and fundamental to all worldly and transcendental interactions.

Pandit Sukhlaal Sanghvi's Contribution:

- Scholarly Analysis: Sanghvi's commentary is a meticulous examination of the Nyayavatar Sutra, offering deep insights into its philosophical arguments and its place in the history of Indian logic.

- Comparative Study: His extensive comparisons with Buddhist and other Indian philosophical traditions are a cornerstone of his work, illuminating the nuances of Jain epistemology.

- Linguistic and Historical Context: Sanghvi provides valuable context regarding the language, style, and historical debates surrounding Siddhasena Divakara and his works.

- Clarification of Complex Concepts: He simplifies intricate logical concepts, making them accessible to students and scholars alike.

- Defense of Jain Philosophy: Sanghvi's commentary implicitly defends Jain philosophical positions against critiques from other schools.

In essence, the Nyayavatar Sutra, as elucidated by Pandit Sukhlaal Sanghvi, is a vital text for understanding the core tenets of Jain logic and epistemology. It presents a sophisticated framework for valid knowledge, emphasizing the multifaceted nature of reality and the importance of various logical standpoints.