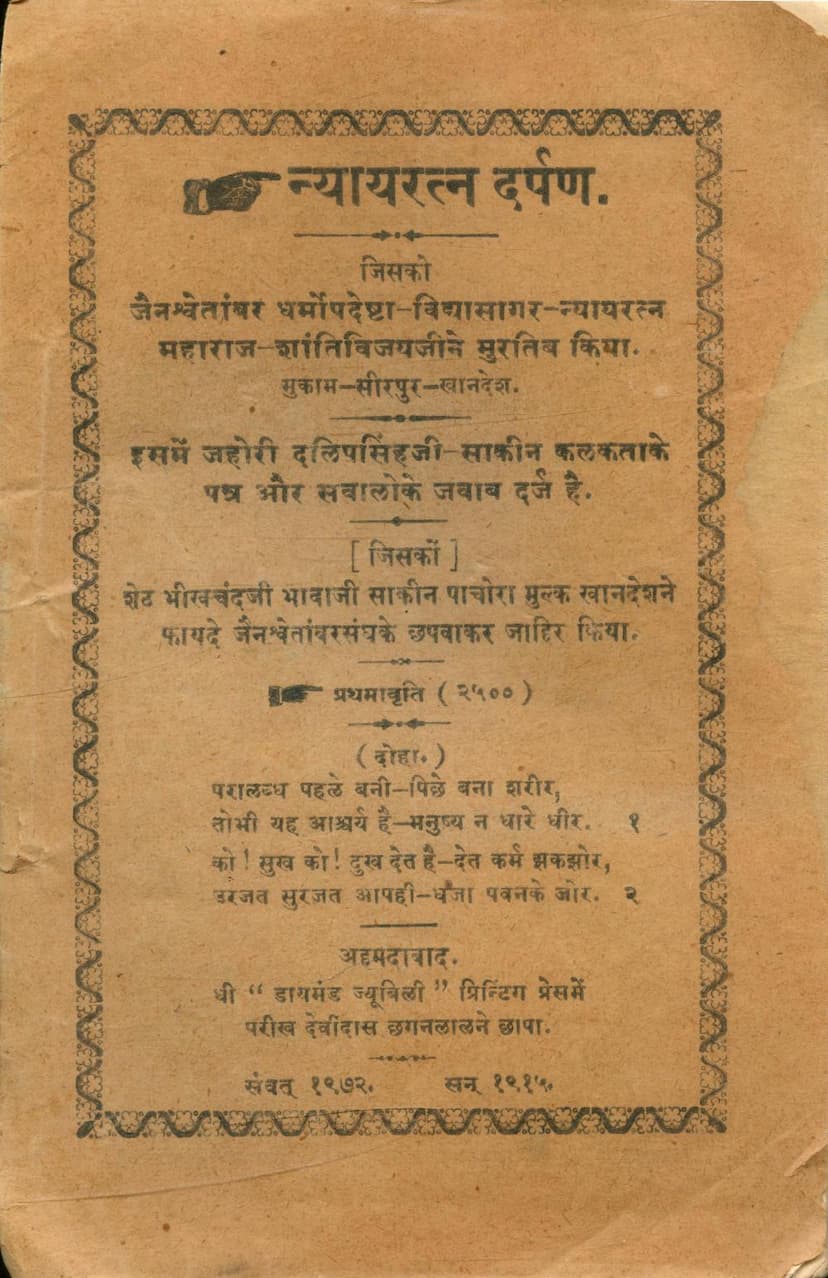

Nyayaratna Darpan

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Nyayaratna Darpan" by Shantivijay, based on the provided pages:

Book Title: Nyayaratna Darpan (Mirror of the Jewel of Justice) Author: Shantivijay (also referred to as Vidyasagar Nyayaratna Maharaj Shantivijay) Publisher: Bhikhchand Bhavaji Sakin Compilation: The book is a compilation of responses from Shantivijay to the letters and questions posed by Jahori Dalipsinghji of Calcutta. Purpose: Published for the benefit of the Jain Shvetambar Sangha, aiming to provide clarity and reasoned answers to religious and philosophical queries.

Introduction and Context (Page 1-3):

- The book, "Nyayaratna Darpan," has been compiled by Jain Shvetambar religious instructor, Vidyasagar Nyayaratna Maharaj Shantivijay.

- It was published by Sheth Bhikhchandji Bhadaji Sakin of Pachora, in the Khanadesh region.

- The text includes responses to letters and seven questions from Jahori Dalipsinghji of Calcutta.

- The author, Shantivijay, expresses his commitment to answering any questions or engaging in discussions presented to him, emphasizing his preference for clear, just, and well-worded responses that benefit the readers. He encourages open dialogue through newspapers or books, rather than solely relying on private correspondence.

- Shantivijay details his extensive travels across India for over twenty years, initially on foot and later by rail, since adopting monastic life in Punjab in Samvat 1936 (1915 CE). He has encountered and benefited Jains from various gacchas (sects).

- He states that he bases his religious writings and answers on scriptural evidence and logical reasoning, considering it his duty and a form of merit to provide accurate answers to religious questions. He believes in conveying religious benefits to his community in an understandable manner.

- The book was motivated by a response Shantivijay gave in a Jain newspaper on July 27, 1913, to Dalipsinghji's questions. Dalipsinghji then published a small book titled "Nyayaratnaji's Injustice and Ut-sutra Propagation" (Nyayaratnaji ki Be-insaafi aur Utsootra Praropna), which contained copies of his letters and seven questions. This book, "Nyayaratna Darpan," is Shantivijay's direct reply to those questions and criticisms.

Key Debates and Questions Addressed (Page 4-26):

The core of "Nyayaratna Darpan" revolves around Shantivijay's detailed responses to Dalipsinghji's criticisms and questions. The primary points of contention and discussion are:

-

The Adhik Maas (Extra Month) and Observance of Fasting Days:

- Dalipsinghji's Allegation: Shantivijay is accused of injustice and "ut-sutra" (unscriptural) propagation by his interpretation of how the Adhik Maas affects the counting of Chaturmas (four-month rainy season retreat), annual fasts, and other religious observances. Dalipsinghji seems to suggest that the traditional counting should be adhered to strictly, even if it means skipping or doubling up on certain days.

- Shantivijay's Defense: Shantivijay argues that the Adhik Maas should not be counted for the purpose of determining the timing of Chaturmas, annual fasts, or other festival observances. He clarifies that if a specific festival day (like Duj, Panchami, etc.) is missed due to the extra month, the observance should be shifted to the preceding day. If two festival days fall on the same day, both should be maintained by observing them on the preceding day. Conversely, if a festival day is extended, the later date should be considered. He uses an analogy of people walking in line to explain this concept of adjustment, stating it is a matter of justice.

- Scriptural Support: Shantivijay cites the Kalpasutra and Samayanganasutra, which mention that Chaturmas is observed after 120 days (50 days of observance + 70 days remaining after Samvatsari). If the Adhik Maas were counted, these durations would be different. He points out that even Dalipsinghji's sect observes Chaturmas in the second Ashadh, not the first, and performs Samvatsari on the 50th day of the Chaturmas, not adhering to the earlier date of the first Ashadh. He also questions why, if Adhik Maas is counted, people don't perform two Chaturmas or two Samvatsaris when two Ashadh or Bhadrapad months occur.

- Dalipsinghji's Counter: Dalipsinghji presents a verse from the "Shraddhavidhi" text and references to texts like Jambudvip Prajnapti and Nishiht Churni, which discuss "Kalachoola" (time extension) and "Kshetra Choola" (spatial extension) in a broader cosmological context, suggesting these imply the counting of the Adhik Maas. He also cites an instance of his Guru's death anniversary occurring in the second Jyest month, questioning why Shantivijay doesn't follow this for festival dates.

- Shantivijay's Rebuttal: Shantivijay reiterates that while these texts may describe the concept of extended years (Abhivardhit Samvatsar), they do not explicitly state that the Adhik Maas should be counted for specific religious observances like Chaturmas. He challenges Dalipsinghji to explain why, if the Adhik Maas is counted, they don't perform multiple observances when two months occur. He concludes that Dalipsinghji's own practices (observing Chaturmas in the second Ashadh) contradict his argument for counting the Adhik Maas for observances. He also clarifies that his Guru's anniversary observance was a specific event, not a universal rule for all festival calculations.

-

Use of Railways by Jain Munis:

- Dalipsinghji's Criticism: Dalipsinghji raises several objections to Jain munis traveling by train, including: the cost of tickets, the need for arrangements from lay followers, the potential for association with women (in separate compartments), the illumination from lamps at night, the increase in luxury and attachment (pramad), the lack of visiting village temples, interruptions in religious discourse to villagers, riding horses from stations at night, missing meal times (gocchari), and the potential for attachment to property due to ticket costs.

- Shantivijay's Defense: Shantivijay argues that the intention behind travel is key. If a muni travels by train with the sole purpose of spreading Jainism and benefiting others, it is not considered sinful. He compares it to a kashai (butcher) buying meat with the intention of satisfying senses versus a jeweler buying a gem for its inherent value. He emphasizes that the absence of attachment and the intention of spiritual benefit are paramount. He states that Jain munis do not desire luxury, but rather arrange for travel through lay followers for the sake of propagating Dharma. He also points out that the lack of visiting temples can occur even with foot-pilgrimages and that train travel can actually facilitate reaching more distant holy sites. He mentions his own extensive travels and research for his book "Jain Teerth Guide" as an example of using travel for religious benefit. He also clarifies that if a muni travels during the day, the issue of night travel and lamps is avoided, and if they are mindful, they can adhere to the proper times for gocchari. He highlights the importance of knowledge and its accessibility, stating that the purpose of his writing is to share knowledge and benefit the community, a duty he feels is fulfilled by such efforts.

-

Discussion on "Ut-sutra" Propagation and Misuse of Scriptures:

- Dalipsinghji's Accusations: Dalipsinghji accuses Shantivijay of "ut-sutra" propagation and of misrepresenting scriptures, particularly regarding the Adhik Maas and the practice of wearing a mouth-cloth (mukhapatti). He cites his Guru, Atmaramji, who stated that those who disobey their Guru's commands are condemned to endless transmigration. He also accuses Shantivijay of not proving the origin of his interpretations of certain verses.

- Shantivijay's Defense: Shantivijay asserts that his teachings are in line with Jain scriptures. He states that he does not engage in "ut-sutra" propagation and has not misrepresented scriptures. He argues that the concept of wearing a mukhapatti during lectures is not explicitly mentioned in any Jain scripture for general practice; its purpose is stated as preventing dust or organisms from entering the mouth or saliva from falling on scriptures. He emphasizes that tradition and practice do not supersede the commands of the Tirthankaras. He clarifies that his Guru's statement about disobedience applies to those who defy scripturally aligned Gurus, not those who follow arbitrary traditions. He challenges anyone to provide scriptural evidence for the practice of wearing a mukhapatti during lectures, stating that if such proof is given, he will cease his opposition.

-

The Practice of Wearing Mukhapatti (Mouth Cloth):

- Dalipsinghji's Stance: Dalipsinghji insists on the importance of the mukhapatti during lectures, citing his Guru Atmaramji and the concept of Guru's commands.

- Shantivijay's Stance: Shantivijay argues that while the use of a mukhapatti is mentioned in texts like the Oghaniryukthi, its purpose is primarily for hygiene (preventing inhalation of dust or contamination of scriptures with saliva) and not as a mandatory practice during lectures in the way it is commonly followed. He states that this practice is not explicitly found in Jain Agamas for general sermon delivery. He emphasizes that scriptural mandate takes precedence over tradition.

Overall Tone and Impact:

- "Nyayaratna Darpan" is a spirited defense of Shantivijay's theological interpretations against direct criticism.

- It highlights a debate within the Jain community regarding the interpretation of religious calendars, the impact of intercalary months on observances, and the appropriate conduct of monastics in modern times.

- The book showcases Shantivijay's erudition, his commitment to reasoned argument, and his desire to educate and clarify for the broader Jain community.

- The inclusion of poetry (Lavani by Surajmalji) at the end further celebrates Shantivijay's life and contributions.

In essence, "Nyayaratna Darpan" serves as a detailed, scripturally supported refutation of criticisms, particularly concerning the Adhik Maas and the conduct of Jain munis, aiming to establish and defend what the author considers the just and accurate application of Jain principles.