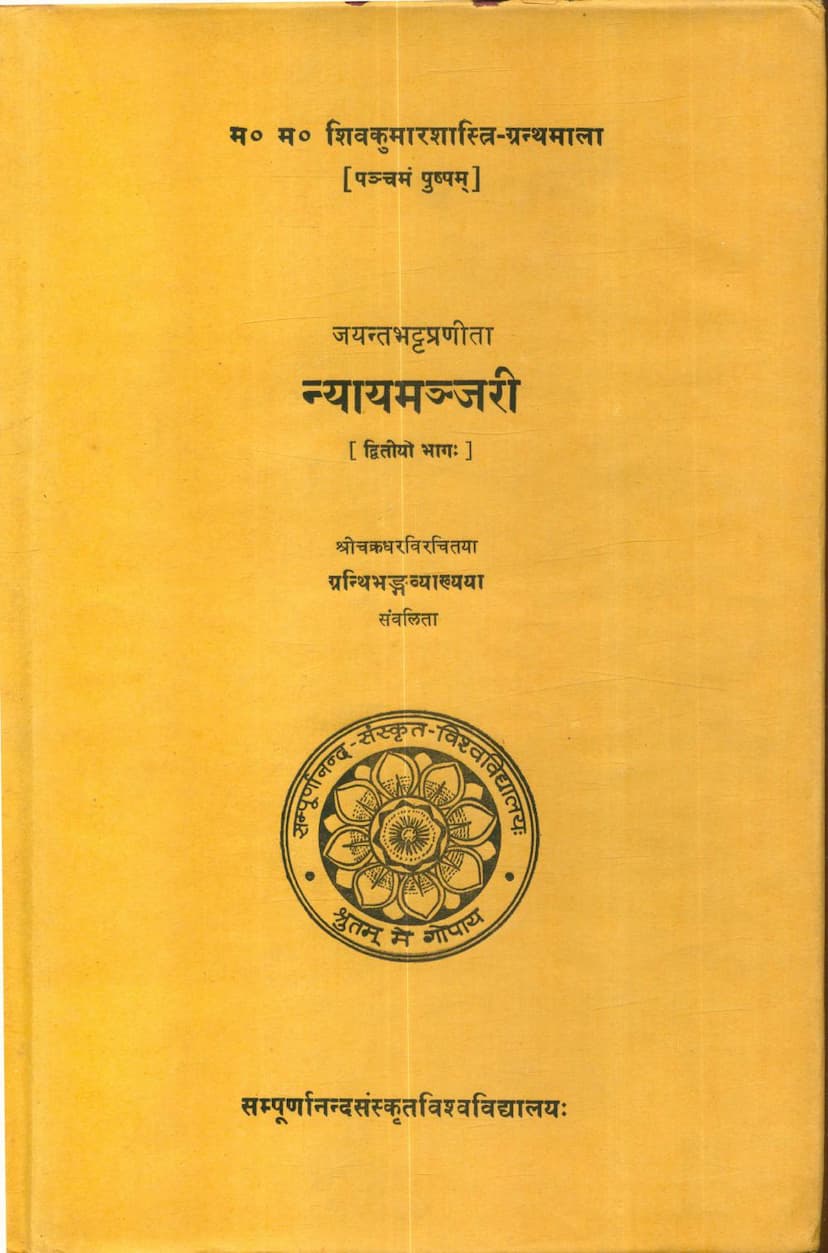

Nyayamanjari Part 02

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

This is a comprehensive summary of Nyayamanjari Part 02 by Jayanta Bhatta, with the commentary 'Granthibhanga' by Chakradhara, and edited by Gaurinath Shastri. The book, published by Sampurnanand Sanskrit Vishvavidyalay in 1983, is the fifth volume in the M. M. Shivakumara Shastri-Granthmala series.

The provided text covers Chapter 5 (Panchama Ahnikam) through Chapter 8 (Ashtama Ahnikam) of the Nyayamanjari. The summary below is organized according to the key themes discussed within these chapters:

Overall Scope:

The Nyayamanjari, as presented in this volume, is a seminal work in Indian logic (Nyaya) and philosophy. Jayanta Bhatta, a prominent proponent of the Nyaya school, addresses various philosophical debates prevalent during his time, engaging with diverse schools of thought including Buddhism, Mimamsa, Saankhya, Vedanta, and Grammar. The text aims to establish the validity of Vedic tradition and the Nyaya system by refuting opposing viewpoints and supporting its own doctrines with rigorous reasoning.

Key Themes and Arguments:

Chapter 5: Pramana Prakaranam (Discussion on Knowledge and Reality - Part 1)

-

The Nature of Word and Meaning:

- Jayanta Bhatta begins by discussing the relationship between words and their meanings, a central topic in Indian epistemology.

- He engages with the Buddhist concept of Apoha, which posits that the meaning of a word is merely a negation of other things, denying the objective reality of universals or individuals. Jayanta refutes this, arguing that words refer to objective realities.

- He delves into the debate on Universals (Jati), refuting the Buddhist denial of their objective existence. Jayanta supports the Nyaya view that universals are real and objective entities, inherent in individuals. He discusses whether universals are pervasive in all instances or only in individuals, and the nature of their perception.

- The text examines the import of words (Subanta), particularly in relation to grammar. Jayanta discusses the Mimamsaka view that the universal (Jati) or form (Akriti) is the meaning of words, contrasting it with the Naiyāyika view that individuals are primary referents.

- He critiques the Mimamsaka insistence on the eternity of the word-meaning relationship to support the unauthored nature of the Vedas.

- Jayanta argues against the notion that words connote only universals (Jati), asserting the necessity of individual (Vyakti) reference, citing scriptural injunctions for rituals that apply to specific actions on individuals.

- The discussions also touch upon the meaning of verbal suffixes (Pratyaya), including case endings, gender, and number, arguing that these grammatical categories are only meaningful when applied to individuals (Vyakti), not abstract universals.

-

The Doctrine of Sabdabrahman (Word as Ultimate Reality):

- Jayanta Bhatta strongly criticizes the Grammarian's doctrine of Sabdabrahman, which identifies the ultimate reality with the word or sound.

- He argues that the concept of a word-principle being eternal and ubiquitous is illogical, as words are limited by time and space.

- Jayanta disputes the Grammarian's claim that all cognition is determinate (Savikalpaka) and inextricably linked to verbal forms. He argues for the existence of indeterminate cognition (Nirvikalpaka) and that cognitions can exist without being associated with words.

- He criticizes Bhartṛhari's view of word as a self-luminous substance, using analogies and pointing out logical inconsistencies in the idea that a word can be both the object and the instrument of cognition.

-

The Import of Words (Linga)

- The text discusses the nature of what words signify, exploring various theories including denotation (Vachya), indication (Dyotaka), and conceptual import.

Chapter 6: Pramana Prakaranam (Discussion on Knowledge and Reality - Part 2)

-

Theories of Meaning (Abhihitanvaya vs. Anvitabhidhana):

- Jayanta Bhatta critically examines the two prominent Mimamsaka theories of sentence comprehension: Abhihitanvaya (meaning of words are understood first, then their relation) and Anvitabhidhana (words directly convey the related meaning). He explains and analyzes the arguments for both.

- He discusses the role of auxiliaries (Upsarga) and particles (Nipata) in conveying meaning, and the debate on their being directly denotative or merely indicative.

-

The Doctrine of Sphota:

- Jayanta Bhatta critiques the Grammarian's theory of Sphota, which posits an indivisible, eternal sound-essence as the ultimate meaning.

- He argues that the sequential experience of letters (Varna) and the resulting impressions (Samskara) are sufficient to explain the cognition of meaning, making the concept of Sphota redundant.

- He points out that Sphota, if it exists, is identified with the primordial sound (Pranava/Om), but argues that its association with Brahman and its incorporeal nature makes its role as a causal principle of creation problematic, especially if it's considered unconscious.

-

Critique of Saankhya and Other Schools:

- Jayanta vigorously attacks the Saankhya theory of Karmendriyas (organs of action), arguing that the Saankhya enumeration is incomplete and many body parts should also be considered sense organs based on their functions.

- He also critiques the Saankhya concept of Antahkarana (inner instrument), the three-fold division of which (manas, buddhi, ahankara) is also questioned.

- He refutes the Saankhya and Advaita Vedanta arguments for Asatkaryavada (the theory that effects do not pre-exist in the cause), which they use to defend their creation doctrines. Jayanta argues that their reasoning leads to logical inconsistencies.

Chapter 7: Prameya Prakaranam (Discussion on Objects of Knowledge)

-

The Self (Atman):

- This chapter extensively discusses the nature of the Self (Atman), a core metaphysical principle.

- Jayanta refutes the Charvaka (Lokayata) view that there is no self beyond the physical body and that consciousness is merely a product of material elements. He argues for the reality of the Self as distinct from the body.

- He addresses the Mimamsaka view that the Self is directly perceived, and the Saankhya view that the Self is distinct from the body.

- Jayanta argues that the continuous sense of "I" (Aham-pratyaya) experienced throughout life, even amidst bodily changes, points to an unchanging Self. He uses arguments from memory (Smriti) and recognition (Pratyabhijna) to support the Self's persistence.

- He criticizes the Buddhist doctrine of Anatmavada (no-self) and Kshanikavada (momentariness), refuting the idea that reality is ultimately momentary and that there is no enduring Self. He analyzes the problem of causal continuity and how momentary entities can produce a continuous experience or memory.

-

The Nature of Consciousness and Mind:

- The text explores the concept of consciousness (Caitanya) and mind (Manas), debating whether they are inherent qualities of the Self or independent entities.

- Jayanta argues against attributing consciousness to the body or the mind as primary causes of experience, leaning towards the Self as the fundamental knower.

Chapter 8: Prameya Prakaranam (Discussion on Objects of Knowledge - Continued)

-

Rejection of Materialism and Consciousness in Elements:

- Jayanta Bhatta continues his refutation of materialistic explanations for consciousness, arguing against the view that consciousness arises from the combination of material elements (Bhuta-chaitanyavada).

- He also dismisses the idea that senses (Indriyas) possess consciousness themselves.

- He discusses the nature of the mind (Manas), questioning the Saankhya division of the inner instrument into Manas, Buddhi, and Ahamkara, and suggesting that the mind's function is to coordinate the senses.

-

The Self as a Permanent Entity:

- Jayanta Bhatta strongly defends the concept of a permanent, unchanging Self (Atman) against the Buddhist and Charvaka views. He uses arguments about continuity of experience, memory, and the sense of "I" that persists across different states of consciousness and bodily transformations.

- He argues that if the Self were merely a collection of momentary consciousnesses or a product of material elements, concepts like moral responsibility, cause and effect, and liberation would become untenable.

-

Critique of Buddhist Philosophy (Momentariness, No-Self):

- The text extensively critiques Buddhist doctrines, particularly the denial of a permanent Self (Anatmavada) and the theory of momentariness (Kshanikavada). Jayanta presents counter-arguments based on the coherence of experience, the existence of memory, and the unity of consciousness.

- He argues that the Buddhist concept of "no-self" fails to explain the continuity of consciousness and the basis for personal identity.

-

The Theory of Asatkaryavada:

- Jayanta Bhatta discusses and refutes the Asatkaryavada, the theory that the effect does not pre-exist in the cause, which is a cornerstone of Saankhya and some other philosophies. He supports the Satkaryavada, the doctrine that the effect pre-exists in the cause, in his own arguments where applicable.

-

The Nature of Causality and Creation:

- The text touches upon the fundamental principles of causality and the origin of the universe, engaging with views that attribute creation to a divine being or to material processes.

Overall Contribution:

This volume of Nyayamanjari provides a detailed exposition and critique of various philosophical positions, showcasing Jayanta Bhatta's mastery of logical reasoning and his profound understanding of the Indian philosophical landscape. The intricate arguments, engagement with opposing schools, and the comprehensive coverage of topics like universals, Apoha, Sabdabrahman, the nature of language, the Self, and causality make this a crucial text for understanding the development of Indian thought, particularly the Nyaya tradition.