Nyayamanjari Part 01

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary of the first part of the Nyāyamañjarī by Jayantabhaṭṭa, as presented in the provided text:

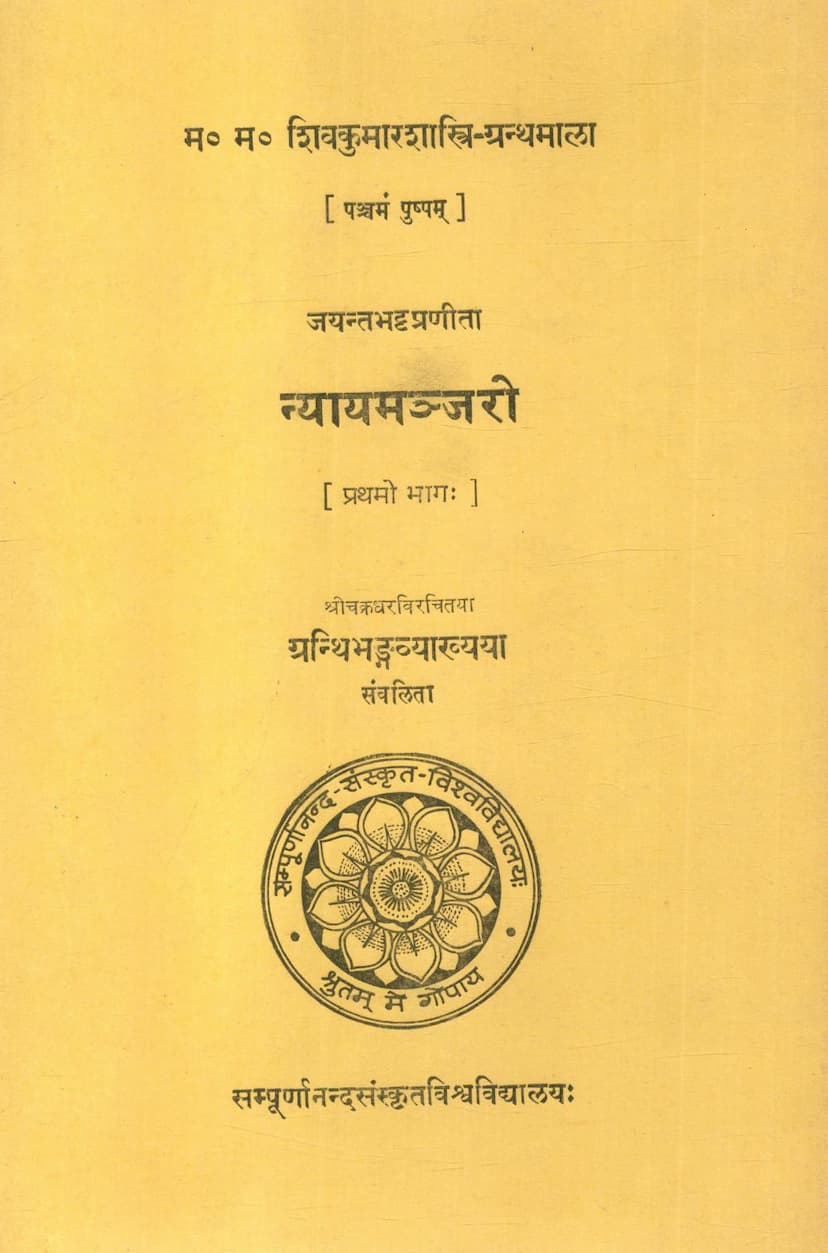

Book Title: Nyāyamañjarī Part 01 Author(s): Jayantabhaṭṭa, with commentary by Cakradhara, edited by Gaurinath Śāstrī Publisher: Sampurnanand Sanskrit Vishva Vidyalay, Varanasi Publication Year: 1982 (Vikrama Samvat 2039, Śaka Era 1904)

Overview:

This edition of Nyāyamañjarī, Part One, presents the first four Āhnikas (chapters) of Jayantabhaṭṭa's seminal work on Indian logic (Nyāya). It includes the commentary "Granthibhanga" by Cakradhara and is edited by Gaurinath Śāstrī. The preface highlights the significance of the Nyāyamañjarī, comparing its value to works like Kumārila's Ślokavārttika and Dharmakirti's Pramāṇa-vārttika. It also mentions previous editions and the importance of Cakradhara's commentary for understanding complex points and identifying unnamed authors and historical data within the original text.

Key Aspects of Jayantabhaṭṭa's Nyāyamañjarī (as described in the preface and text):

- Epoch-Making Work on Indian Logic: Nyāyamañjarī is considered a foundational text for the study of the Nyāya system.

- Champion of Nyāya: Jayantabhaṭṭa is presented as a formidable defender of the Nyāya philosophical system.

- Versatile and Scholarly Personality: He possessed a rare breadth of outlook, analyzing and explaining opponents' views with precision and integrity. His ability to restate opposing schools' arguments with such clarity that they might not be found in their own texts is remarkable.

- Mastery of Diverse Philosophical Systems: Jayantabhaṭṭa demonstrated an enviable mastery of various systems, including Vedic traditions, Mimāṁsā, Buddhism, and Jainism. This contributed to his own radiant philosophical stature.

- Humorous and Engaging Style: His writing style is praised for its grammatical mastery, literary art, and the unique quality of presenting abstruse logical points in a way that provides relief and aids the reader's understanding. His frequent and spontaneous humorous expressions reveal a genial personality that draws readers to his side.

- Respect for Opponents' Views: While firmly rooted in his own convictions, Jayantabhaṭṭa possessed the catholicity to admire the cogency in arguments of his opponents, even when ultimately refuting them.

- Advocacy for Vedic Authority: Jayanta placed a strong foundation for the authority of the Vedas, arguing more convincingly than many Mimāṁsakas. His arguments, particularly regarding the authority of the Atharvaveda, suggest a personal allegiance to its traditions.

- Critique of Kumārila and Buddhists: Jayanta's self-confidence enabled him to critique Kumārila and others with courage and conviction. His familiarity with Buddhist scholars like Diṅnāga and Dharmakirti was so thorough that his presentation of their views was precise, methodical, and intimate, highlighting his intellectual honesty and fairness.

- Other Works: Besides Nyāyamañjarī, he authored Nyāyakalikā (an abstract for beginners) and Nyāyapallava. His play, Āgamādambara, showcases his poetic talents and elegant prose. A commentary on Pāṇini (Vṛtti on Aṣṭādhyāyi) is also mentioned.

- Historical Context: Jayantabhaṭṭa is identified as a contemporary or successor of Vācaspati Miśra (who commented on Nyāyasūtra I.i.6 in light of Jayanta's views), and likely preceded Udayanācārya. He served as a minister to King Śankaravarman of Kashmir (885-902 A.D.), though Kalhaṇa does not mention him. He quotes Kālidāsa and Bāṇa with high praise and mentions Vāgha, the poet of Śiśupālavadha. The commentator Cakradhara identifies "Rājā" mentioned by Jayanta with the Rāja-vārttikakāra, potentially King Mihirabhoja (late 9th century).

- Personal Details: Jayanta belonged to a devout Śaiva tradition, was the son of Candra, grandson of Kalyāṇasvāmin, and his son was Abhinanda, author of Kādambarīkathāsāra.

- Interpretation of "Confinement": The text explores a passage where Jayanta describes being placed in confinement by the king. The modern interpretation suggests it might refer to his stay in a Khasa region on official duty, rather than literal imprisonment, due to the calm and serene atmosphere being conducive to writing.

Summary of the First Āhnika (First Part):

The first Āhnika focuses on the fundamental principles of logic and epistemology. Key discussions include:

- The Nature of Knowledge and Scripture: Jayanta argues for the importance of logic (Ānvīkṣikī) as a foundational discipline that establishes the authority of the Vedas. He counters the Mimāṁsā view of the Vedas' self-validity (svataḥ pramāṇya) by asserting the need for logical reasoning (anumāna) to establish God as the author of the Vedas, thereby validating them (parataḥ pramāṇya).

- The Purpose of Logic: Jayanta explains that logic is crucial for refuting the flawed arguments of rival philosophers (Tārkikas, Buddhists, Jainas, Cārvākas) who corrupt the authentic meaning of the Vedas. It serves as a "lamp" for all knowledge and a means to establish the truth.

- Categories of Knowledge (Pramāṇa): The text elaborates on the Nyāya categories of knowledge (Pramāṇa), discussing perception (pratyakṣa), inference (anumāna), comparison (upamāna), and testimony (śabda).

- Theories of Perception: Jayanta analyzes different schools' definitions of perception, including the significance of the "uninterrupted" (avyabhicārī) and "determinative" (vyavasāyātmaka) aspects of knowledge.

- The Role of Causality and Apprehension: The text delves into the nature of instruments of knowledge (karaṇa), the collection of causes (sāmagrī), and the debate on whether knowledge itself or its instrument is the real 'pramāṇa'. Jayanta argues for the inherent potency of the collection of causes (sāmagrī) as the 'karaṇa'.

- Critique of Buddhist Epistemology: Jayanta thoroughly analyzes and critiques the Buddhist theories of perception and inference, particularly their focus on 'kṣaṇa' (momentariness) and their rejection of external reality.

- The Concept of 'Shakti' (Potency): Jayanta discusses and largely refutes the concept of 'shakti' (inherent potency) as an unnecessary metaphysical entity in explaining causal relationships, favoring a more logical and empirical approach.

- The Nature of 'Abhāva' (Non-existence): Jayanta engages with various theories of non-existence, including prāgabhāva (prior non-existence), dhvamsābhāva (posterior non-existence), itaretarābhāva (mutual exclusion), and atyantābhāva (absolute non-existence), often critiquing other schools' interpretations.

This edition aims to provide a comprehensive and accessible resource for students and scholars of Indian logic, offering the text and its essential commentary in a structured format. The preface emphasizes the text's intellectual rigor, historical importance, and the editor's dedication to presenting it accurately.