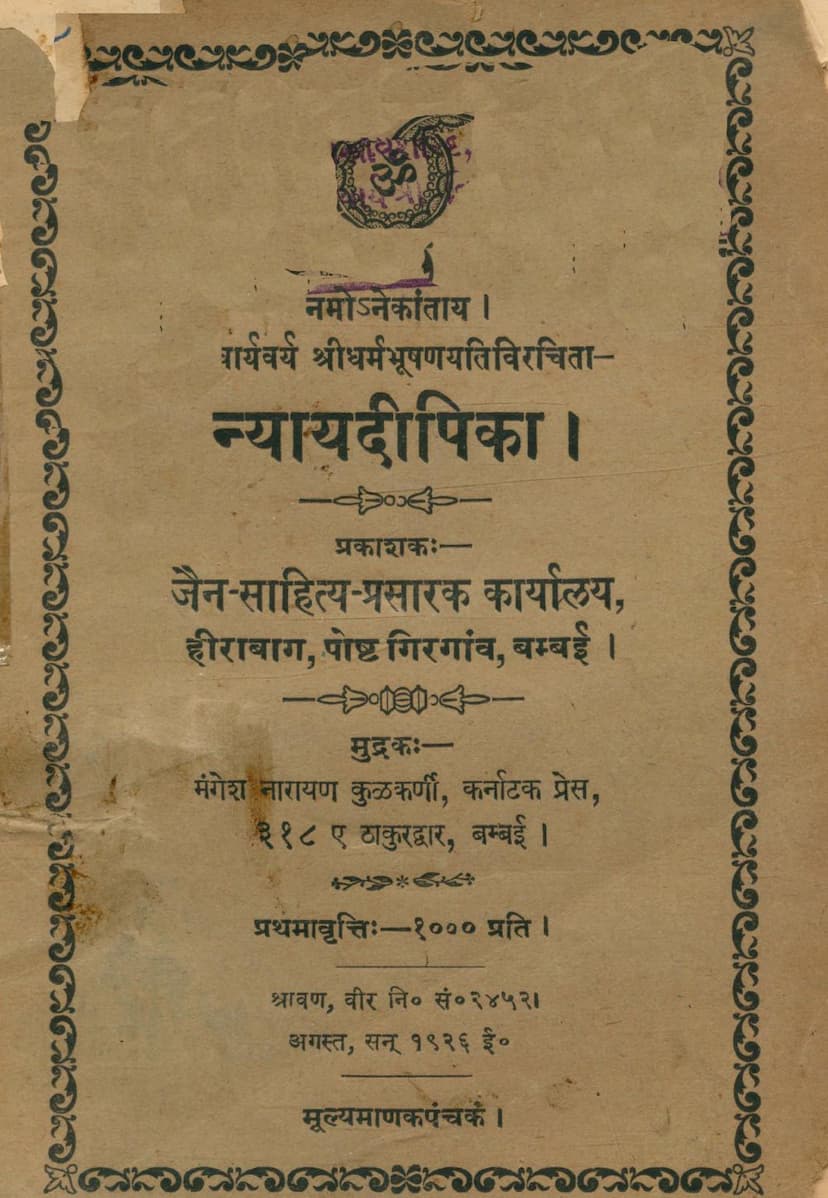

Nyayadipika

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

The "Nyayadipika" (Lamp of Logic) by Dharmbhushan Yati is a foundational text in Jain epistemology and logic. Published by Jain Sahitya Prasarak Karyalay in Bombay in 1926, it aims to explain the principles of knowledge and reality in a way that is accessible to both beginners and scholars.

The book is structured into three "Prakashas" (sections or chapters):

First Prakash: On Pramana (Means of Valid Knowledge)

- Introduction: The author begins by acknowledging the importance of the Tattvartha Sutra's statement, "Acquisition of knowledge is through pramana and naya." He explains that understanding the soul and other Jaina principles is achieved through these two. He notes that while existing texts on pramana and naya are extensive or profound, making them difficult for beginners, this work aims to provide a clear exposition of their nature for the benefit of the less initiated.

- Methodology: The discussion of pramana and naya will be conducted through uddesha (statement of the topic), lakshana (definition), and pariksha (examination/analysis).

- Definition of Lakshana: The author clarifies that a lakshana (definition) is that which helps to distinguish an object. He categorizes lakshana into intrinsic (atmabhuta) and extrinsic (anatabhuta). An intrinsic definition is part of the object's essence (e.g., heat for fire), while an extrinsic one is external (e.g., a stick for a person). He criticizes the view that a definition is merely a statement of an uncommon property, as this can lead to over-inclusion (ativyapti) or under-inclusion (avyapti).

- Definition of Pramana: The core definition presented is "correct knowledge is pramana."

- The Role of "Samyak" (Correct): The word "correct" is used to exclude incorrect cognitions like doubt (samsaya), error (viparyaya), and indecision (anadhyavasaya). Doubt arises from perceiving common features without distinguishing elements. Error is a mistaken certainty about something. Indecision is mere contemplation without certainty. These are not pramana because they don't yield true knowledge.

- The Role of "Jnana" (Knowledge): "Knowledge" is used to distinguish pramana from the knower (pramatu) and the act of knowing (pramiti). The text clarifies that "knowledge" here is a karana sadhana (instrumental noun), meaning "that by which something is known," rather than bhava sadhana (noun of state), which would refer to the act of knowing itself. Thus, pramana is the instrument that leads to correct knowledge.

- Overcoming Objections (Ativyapti): The author addresses potential over-applications of the definition:

- Sensory Organs (Aksha): Sensory organs like eyes are instruments for knowing, but they are not the ultimate instrument (sadhakatama). They are unconscious and lack self-illumination. True instruments must be knowledge-revealing and non-contradictory to ignorance. The use of "known by the eye" is considered metaphorical.

- Continuous Cognitions (Dharavahika Buddhi): These are not considered pramana in the Jaina view because the object has already been known by the first cognition. Subsequent cognitions are merely repetitions (grihita grahitva).

- Nirvikalpaka (Indeterminate Perception): This is excluded because it is considered indecisive (anadhyavasaya) and not a direct cognition of the object's reality.

- Nature of Validity (Pramanya): The validity of pramana is defined as non-contradiction with the manifested object.

- Origin of Validity: Mimamsakas believe validity arises spontaneously, but the author argues it must arise from something else, just as the invalidity of erroneous knowledge does. Therefore, validity, like invalidity, is acquired from external factors (paratattva).

- Cognition of Validity: Validity is known spontaneously for familiar objects and externally for unfamiliar ones.

Second Prakash: On the Specific Nature of Pramana (Direct and Indirect)

-

Two Types of Pramana: Pramana is divided into Pratyaksha (Direct Perception) and Paroksha (Indirect Knowledge).

-

Pratyaksha (Direct Perception):

- Definition: Clear manifestation (vishada pratibhasa).

- Nature of Clarity: Clarity is a state of purity achieved through the partial subsidence of obscuring karmas. It is a direct experience of clarity, as distinct from the knowledge derived from words or inference.

- Critique of Other Views:

- Bauddhas (Buddhists): Their definition of pratyaksha as "imagination-free and non-erroneous" is rejected because indeterminate perception (nirvikalpaka), which they consider pratyaksha, is itself problematic and lacks certainty.

- Yogas: Their definition of pratyaksha as "contact between sense organs and objects" is rejected because sense organs are limited to present objects and the Jaina view includes non-sensory direct perception. The self-illuminating nature of the soul (atma) and the concept of indirect perception through the senses are discussed.

- Two Types of Pratyaksha:

- Samvyavaharika Pratyaksha (Conventional Direct Perception): This is clear in terms of space. It is fourfold:

- Avagraha: The initial perception of an object, grasping its general form.

- Iha: An effort to ascertain the specific nature of the object.

- Avasaya: The determinate knowledge or conclusion about the object.

- Dharana: Retention of the knowledge. These arise from sensory or mental apprehension and are considered conventional because they are still tied to sensory or mental processes.

- Paramarthika Pratyaksha (Ultimate Direct Perception): This is clear in all respects. It is divided into:

- Vikala (Limited): Perceives a limited scope.

- Avadhi Jnana: Direct knowledge of subtle, distant, or past/future physical objects, arising from partial destruction of obscuring karmas.

- Manahparyaya Jnana: Direct knowledge of the thoughts of others, arising from greater subsidence of obscuring karmas.

- Sakala (All-encompassing): Perceives all substances and their modifications. This is Kevala Jnana (Omniscience), achieved after the complete destruction of all obscuring karmas.

- Vikala (Limited): Perceives a limited scope.

- Samvyavaharika Pratyaksha (Conventional Direct Perception): This is clear in terms of space. It is fourfold:

- The Omniscience of Arhats: The author argues for the existence of omniscience in Arhats through inference, based on the principle that subtle, intervening, and distant objects are directly perceived by someone, just as fire is inferred from smoke. He further supports this by arguing that Arhats are flawless (nirdosha) and that flawlessness, particularly freedom from obscuring karmas, can only be attained through omniscience.

-

Paroksha (Indirect Knowledge):

- Definition: Unclear manifestation (avishada pratibhasa).

- Critique of Other Views: Views that define paroksha as knowledge of only generals are rejected, as both direct and indirect knowledge encompass both general and specific aspects.

- Five Types of Paroksha:

- Smriti (Memory): Recollection of past experiences, requiring an underlying impression (dharana).

- Abhinnijana (Recognition): Also known as Pratyabhijna. It involves recognizing an object as "this very thing," combining memory and present perception to establish identity or similarity. The author refutes attempts to classify this under perception or other categories, establishing it as a distinct form of paroksha.

- Tarka (Reasoning/Logic): The process of inferring the relationship (e.g., vyapti or invariable concomitance) between a probans (hetu) and a probandum (sadhyam). The author argues for its necessity as a separate means of knowledge.

- Anumana (Inference): Knowledge of the probandum derived from the probans, based on the established vyapti. The author clarifies that anumana is the knowledge of the probandum, not just the contemplation of the probans. He discusses the components of inference (subject, predicate, probans) and the necessity of a valid probans (hetu) that has the characteristic of "otherwise unexplainable" (anyathanupapatti). He critiques the five-membered syllogism of the Nyayikas, stating that only the proposition (pratijna) and the reason (hetu) are essential for inference, especially in debate.

- Agama (Testimony): Knowledge derived from the words of a reliable authority (upta). An upta is defined as one who has known all things directly and is a preacher of ultimate welfare. The author emphasizes the crucial role of "meaning" or "intention" (artha or tatparya) in valid testimony. The Jaina Agamas are presented as the primary example of valid testimony.

Third Prakash: On Agamas (Scriptural Authority) and Naya (Standpoints)

- Agama (Scriptural Authority):

- Definition: Knowledge of meaning based on the words of an upta.

- The Nature of "Artha": The ultimate "meaning" of reality is described as anekanta (multi-facetedness). This refers to the co-existence of generalities (samanya), specifics (vishesha), modes (paryaya), and qualities (guna) in all substances (dravya).

- The Nature of Dravya: Substances are characterized by origination, cessation, and permanence (utpadavyayadhrauvyayuktam sat). The author discusses the Jiva (soul) and Ajiva (non-soul) substances, and their characteristics.

- Naya (Standpoints):

- Definition: A particular perspective or emphasis chosen by the knower from the manifold aspects of reality apprehended by pramana.

- Two Primary Nayas:

- Dravyarthika Naya (Substance-oriented Standpoint): Focuses on the substantial aspect of reality, emphasizing unity and permanence. It sees diversity as secondary.

- Paryayarthika Naya (Mode-oriented Standpoint): Focuses on the modal or specific aspect of reality, emphasizing diversity and impermanence.

- Saptabhangi (The Sevenfold Predication): The interaction of these standpoints leads to the doctrine of saptabhangi, which posits that reality can be described from seven different perspectives (e.g., "is," "is not," "is and is not," "is indescribable"). The author explains how these standpoints lead to different, seemingly contradictory, but valid descriptions of reality.

- The Role of Syadvada: The principle of syadvada (perhaps-ism) is inherently linked to naya, acknowledging that any statement about reality is true only from a particular standpoint.

Conclusion:

The "Nyayadipika" systematically presents the Jaina epistemological framework, defining pramana and naya and refuting alternative views. It highlights the Jaina understanding of direct and indirect knowledge, the nature of inference, the authority of scripture, and the multifaceted nature of reality as understood through different logical standpoints. The work emphasizes clarity and accessibility, making it a valuable resource for understanding Jaina philosophy.