Nyayadarshanasya Nyayabhashyam

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

The Jain text provided is a commentary called "Prasannapada" on Vatsyayan's "Nyaya Bhashya," which is itself a commentary on Gautama's "Nyaya Sutras." The text you've provided appears to be the introductory and index sections of this work, with a particular focus on establishing the authorship and chronological context of the various texts and commentaries within the Nyaya tradition.

Here's a comprehensive summary based on the provided pages:

1. Book Identification and Publication:

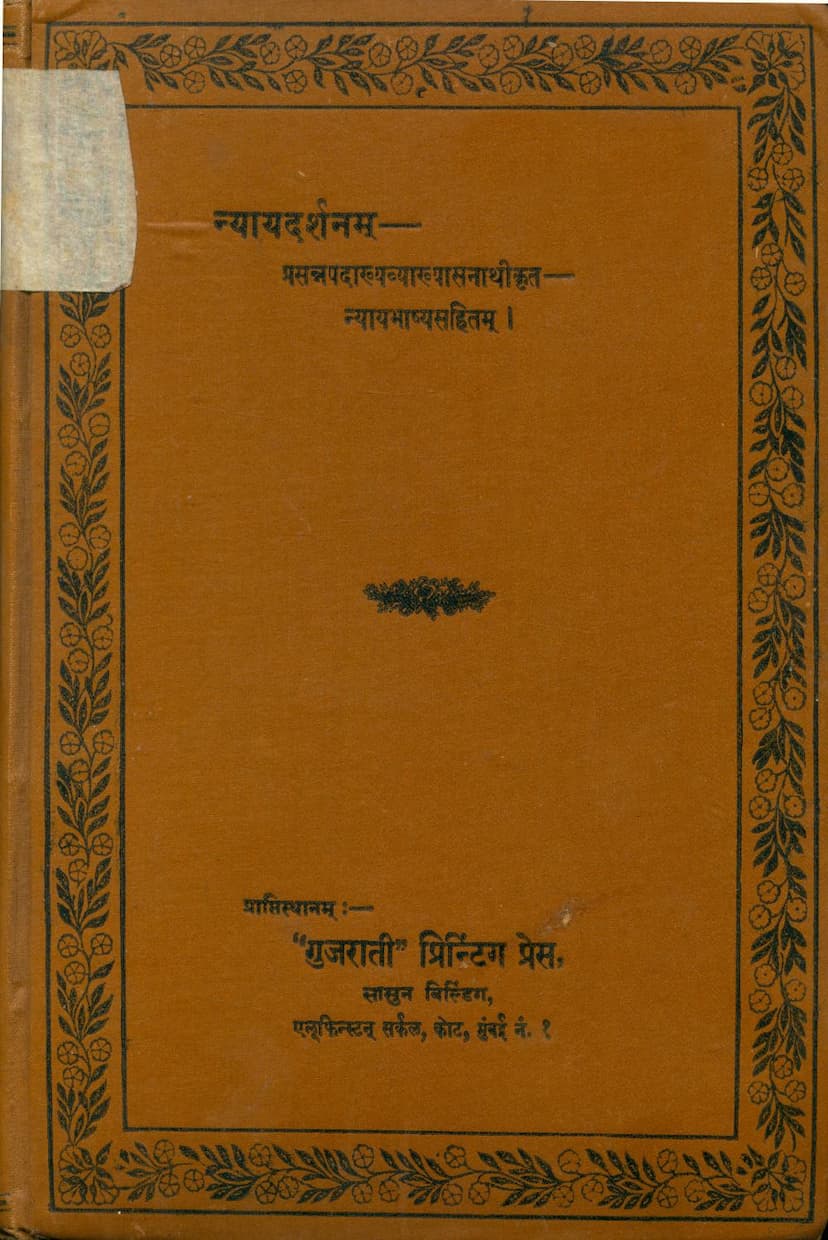

- Title: Nyayadarshanasya Nyayabhashyam (with commentary Prasannapada)

- Author of the Original Nyaya Sutras: Gautama ( न्यायाचार्यश्रीगौतमप्रणीतन्यायसूत्राणाम्)

- Author of the Nyaya Bhashya: Vatsyayan (विद्वद्वरश्रीवात्स्यायनविरचितम्)

- Author of the Prasannapada Commentary: Sudarshanacharya Shastrin (from Panchanadi) (पश्चनदीयपण्डितसुदर्शनाचार्यशास्त्रिप्रणीतया प्रसन्नपदाख्यव्याख्यया विभूषितम् टीकाकत्रैव च संशोधितम्)

- Publisher: Manilal Iccharam Desai (मणिलाल इच्छाराम देशाई)

- Printing Press: "Gujarati" Printing Press, Sassoon Building, Fort, Bombay (गुजराती मुद्रणयन्त्रालये)

- Publication Year: 1922 (खिस्ताब्दाः 1922)

- Price: 3 Rupees (मूल्यं 9 रूप्यकाः)

2. Introduction to Nyaya Philosophy (Bhumika - Page 4):

- The introduction acknowledges the existence of multiple philosophical systems in India.

- It highlights Nyaya as one of the six principal darshanas (philosophical schools).

- Key tenets of Nyaya mentioned include:

- Ishvara (God) is formless, possessed of eternal knowledge and other qualities, and is the efficient cause of the universe.

- Jivas (souls) are infinite and all-pervading. Their knowledge and other qualities are due to their conjunction with manas (mind). They are distinct from Ishvara.

- Akasha (space) is eternal. The other elements (bhutas) have atoms (paramanu) as their eternal constituents, from which gross elements are formed through a sequential process.

- Moksha (liberation) is attained through the knowledge of the essence of substances like the soul, leading to the cessation of desires and attachments.

- The introduction expresses skepticism about Gautama, the author of the Nyaya Sutras, being the same as the Gautama Maharshi, the husband of Ahilya, finding no conclusive evidence. It also criticizes the sutras themselves for lacking clarity.

3. Examination of Vatsyayan's Time and Authorship (Vatsyayan Samay Samiksha - Pages 6-8):

This is a significant portion of the introduction, attempting to establish Vatsyayan's identity and historical period. The author, Sudarshanacharya, presents a detailed argument suggesting that Vatsyayan, the author of the Nyaya Bhashya, is the same person as Chanakya (also known as Kautilya, Vishnugupta), the author of the Arthashastra and the Kamasutra.

-

Evidence for Vatsyayan = Chanakya:

- Lexical Evidence: Cites ancient lexicographical texts (Abhidhanachintamani, Trikanḍasheshkosha) which list various names associated with Chanakya, including Mallanaga, Pakshilasvami, Vishnugupta, Angula, and importantly, Vatsyayana. The author suggests "Kaundinya" in one verse might be a corruption of "Kautilya."

- Stylistic Similarities: Notes similarities in writing style between the Nyaya Bhashya and works attributed to Patanjali and possibly others, suggesting Vatsyayan's proximity in time to these figures.

- Shared Philosophical Concepts: Points out identical discussions on the classification of sciences in the Nyaya Bhashya (" anvīkṣikī is the fourth of the four vidyās...") and Chanakya's Arthashastra (Vidyāsamuddeśa chapter).

- Similar Concepts in Word Definition: Compares the definition of " pada " (word) in the Nyaya Bhashya to that in the Arthashastra, finding them to be the same.

- Quotations of Verse: Notes that a verse about anvīkṣikī quoted at the end of the first sutra of the Nyaya Bhashya is also found in Kautiliya Arthashastra's Vidyāsamuddeśa, with a concluding remark indicating it was prakīrtita (mentioned earlier), implying Kautilya mentioned it first.

- Shared Anecdotes: Mentions that certain narratives found in the Arthashastra's Shāsanādhikāra chapter are also found in the Nyaya Bhashya's commentary.

- Kamajñāna (Erotic Knowledge): Suggests Vatsyayan's authorship of the Kamasutra indicates a preoccupation with kama (pleasure), which the author links to potential "pramāditvam" (carelessness) in his writing, which is also observed in the sutras.

- Other Names: Mentions "Mallanaga" and "Pakshilasvami" as names associated with Vatsyayan, who are also potentially linked to Chanakya.

-

Chronological Placement: Based on the Vishnu Purana's description of Nandas and Chandragupta's reign, the author places Chanakya (and thus Vatsyayan) around 383 BCE (approximately 3900 years after the start of the Kali Yuga). Another quote from Skanda Purana suggests an earlier date of 2700 BCE. The author favors the later date due to its alignment with modern scholarly consensus.

4. Critiques of Philosophical Systems and Contemporary Society (Pages 10-11):

This section presents a scathing critique of various philosophical schools and the state of religious and societal practices in India during that era. The tone is highly critical and cynical.

- Philosophical Systems:

- Contradictory nature of philosophies.

- Inconsistency in defining fundamental concepts like the size of the soul (parimāṇa), eternity (nityatva), and the nature of the universe (prapañca).

- Accusation of philosophies being driven by personal desires (rāga-dveṣa-krodha-ādi) for establishing their own doctrines rather than for the welfare of the world.

- Accusation of manipulating scriptural texts (śruti) to support their views.

- Criticism of disciples upholding their gurus' exaggerated importance, making even the Supreme Being (Paramaatma) seem like a servant.

- Assertion that these philosophies have increased suffering (anarthānam vr̥ddhireva kr̥tā) rather than removed it.

- Religious and Societal Practices:

- Criticism of various religious sects (Brahmavādins, Vaishnavas, Shaivas, Shaktas) for their destructive criticism of each other.

- Deities are portrayed as mere playthings of their worshippers.

- Contemporary religious leaders are depicted as hypocritical, fearlessly speaking falsehoods, considering people fools, acting as they please, promoting notions like liberation through initiation (dīkṣā) or divine grace through monetary donations (kārṣāpaṇa).

- A strong indictment of the perceived moral and spiritual decay of society, highlighting:

- Abortion as a form of chastity.

- Prostitution coexisting with marital fidelity.

- Envy disguised as peace.

- Self-interest presented as altruism.

- The prevalence of cunning individuals, impure practices (eating beef fat mixed with ghee), and litigiousness.

- A sense of hypocrisy where people appear pious externally but are corrupt internally.

5. Index/Table of Contents (Pages 12-19):

These pages provide an extensive index of the Nyaya Sutras according to their chapter and aphorism numbers (e.g., अ. आ. सू. सं. । सूत्राणि). This indicates the structure and scope of the original Nyaya text being commented upon.

6. Specific Sutra Explanations (Pages 20-59):

These pages contain detailed explanations and interpretations of specific Nyaya Sutras by Sudarshanacharya Shastrin in his "Prasannapada" commentary. This part goes into the philosophical arguments and debates within Nyaya and its related schools. Key topics covered here include:

- Pramanas (Means of Knowledge): Detailed examination of perception (pratyakṣa), inference (anumāna), comparison (upamāna), and testimony (śabda).

- Arguments about the Nature of Reality: Discussions on categories like artha (meaning/substance), tattva (essence), samsaya (doubt), and niṛṇaya (conclusion).

- Arguments about the Soul (Ātman): Debates on the soul's existence, its pervasiveness, and its relationship with the body and senses.

- Debates on Word and Meaning: Discussions on the nature of words, their relation to meaning, and the validity of language.

- Debates on Causality: Examination of different theories of causation.

- Critique of Other Philosophies: Brief mentions of critiques against Buddhist and Sankhya philosophies.

- Logical Fallacies (Hetvābhāsa): Identification and explanation of various logical fallacies.

- Forms of Argumentation: Discussion of vāda (debate), jalpa (wrangling), and vitāṇḍā (caviling).

7. Explanations of Specific Sutras (Pages 59 onwards):

The later pages delve into detailed explanations of specific sutras, demonstrating the commentary's purpose: to clarify difficult passages and provide a rationale for the philosophical arguments. This includes intricate breakdowns of:

- The definition of perception (pratyakṣa): Discussing its conditions, such as sensory contact and the role of manas.

- The nature of inference (anumāna): Explaining its types (e.g., pūrvavat, śeṣavat, sāmānyato dṛṣṭa) and the role of logical connection (liṅga).

- The nature of comparison (upamāna): Explaining how similarity (sādharmya) is used for knowledge.

- The validity of testimony (śabda): Debating its reliance on an "apt" (trustworthy) source.

- The existence and nature of the Soul (ātman): Arguments from memory, desire, and introspection.

- The relationship between senses and the soul: Examining how senses function and their perceived connection to the soul.

- The nature of cause and effect: Discussing various theories.

- The concept of time: Examining the relation of events to past, present, and future.

- The nature of sound (śabda): Debating its eternality or transience.

Overall Impression:

This text is a scholarly and critical commentary on a foundational work of Indian philosophy. The author, Sudarshanacharya Shastrin, demonstrates a deep knowledge of the Nyaya tradition and its history, engaging in critical analysis of earlier scholars and philosophical positions. The introduction is particularly striking for its bold assertion about Vatsyayan's identity as Chanakya, supported by considerable textual evidence. The later sections, while philosophical, reveal the author's keen analytical approach to complex arguments. The concluding sections offer a critique that reflects a disillusionment with the prevailing spiritual and intellectual climate of his time. The inclusion of an extensive index and detailed explanations of sutras underscores the text's function as a comprehensive guide to the Nyaya Bhashya.