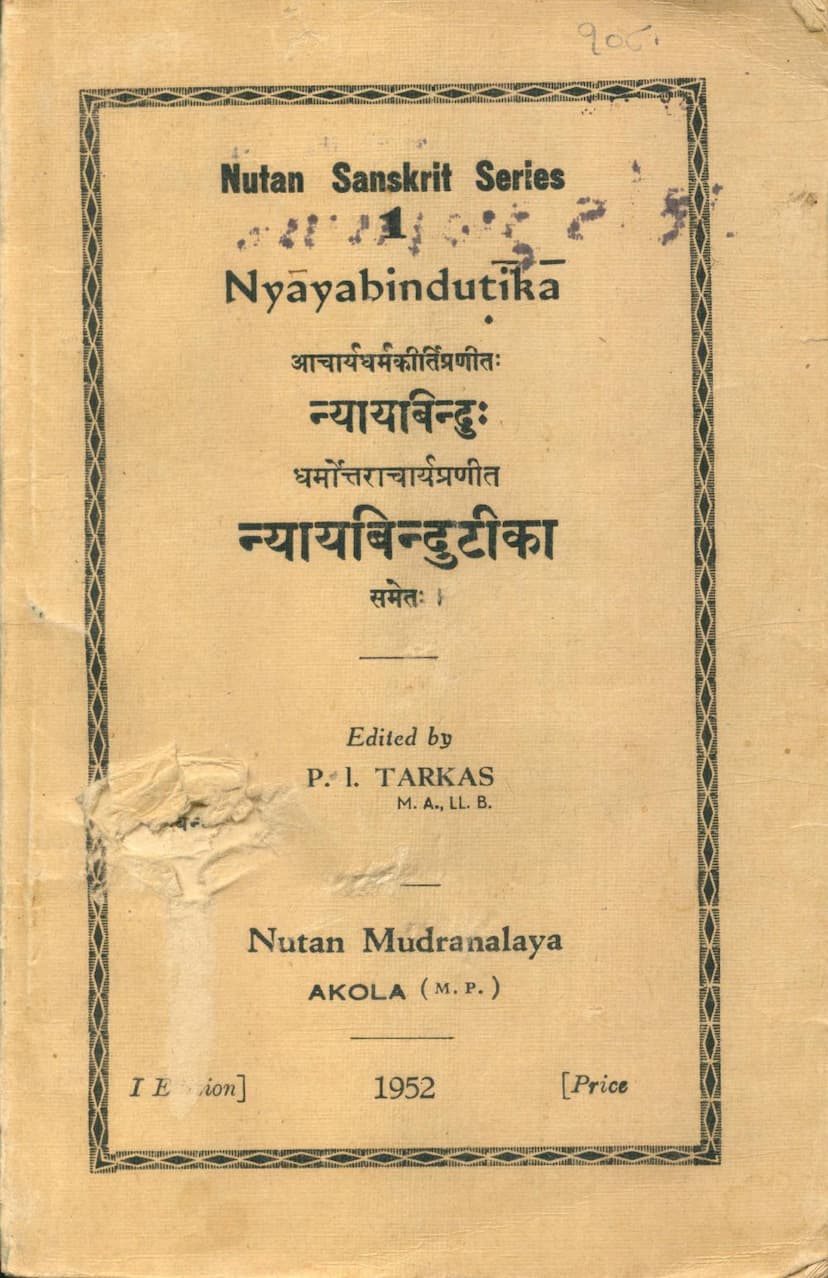

Nyayabindu Tika

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Nyayabindu Tika" by Acharya Dharmakirti, with a commentary by Dharmottara, as edited by P. I. Tarkas:

Overall Purpose and Structure:

The Nyayabindu (literally "Drops of Logic") is a foundational text in Buddhist epistemology and logic, particularly within the Dignāga-Dharmakīrti school. It aims to establish the validity of knowledge and the means to attain it, ultimately leading to liberation. The Nyayabindu Tika is a detailed commentary on this text by Dharmottara, providing explanations, clarifications, and refutations of opposing views. This edition, published by Nutan Mudranalay in 1952, is a Sanskrit text with an English introduction and commentary by P. I. Tarkas.

The text is structured into three main chapters:

- Chapter 1: On Perception (Pratyaksha)

- Chapter 2: On Inference (Anumana)

- Chapter 3: On Syllogisms (Punararthanumana)

Key Concepts and Arguments:

Chapter 1: Perception (Pratyaksha)

- The Goal: The opening verse establishes that the attainment of all human goals (puruṣārtha) is preceded by right knowledge (samyagjñāna), and this text aims to elucidate that knowledge.

- Definition of Right Knowledge: Right knowledge is defined as that which does not mislead (avisamvādakam). It is knowledge that leads one to the intended object, effectively guiding action.

- Two Types of Right Knowledge: The text identifies two primary means of valid knowledge:

- Perception (Pratyaksha): Direct, unmediated apprehension of reality.

- Inference (Anumana): Knowledge derived from a logical sign (linga) that is invariably connected to the object.

- Definition of Perception: Perception is characterized as:

- Free from Conceptualization (kalpanapoḍham): It is a pure, direct apprehension that does not involve the imposition of concepts, names, or universals. This distinguishes it from inferential knowledge.

- Error-Free (abhrāntam): It accurately represents the object as it is.

- Factors Causing Illusions: The text explains how errors in perception arise, attributing them to external factors (like dimmed vision, rapid movement of objects, physical distress) or internal states (like illness, psychological disturbances).

- Types of Perception: The text elaborates on different forms of perception:

- Sense-Perception (indriyajñāna): Arising from the interaction of sense organs with their objects.

- Mental Perception (manovijñāna): The cognition that follows immediately after sense-perception, apprehending the mental aspect of the experience.

- Self-Awareness (svasaṃvedana): The capacity of consciousness to be aware of its own states.

- Yogic Perception (yogijñāna): A highly refined and direct perception attained through deep meditative practice, capable of apprehending subtle realities.

- Object of Perception: The object of perception is the particular instance (svalakṣaṇa), the unique, momentary existence of a thing, stripped of conceptual overlays. This unique particular is the ultimate reality (paramārthasat).

- Distinction from Universals: Universals (sāmānyalakṣaṇa), which are common characteristics shared by multiple particulars, are the objects of inference, not direct perception.

Chapter 2: Inference (Anumana)

- Two Types of Inference: Inference is divided into:

- Inference for Oneself (svārthānumāna): The logical process of arriving at knowledge through a sign.

- Inference for Others (parārthānumāna): The reasoned argument presented to convince another, typically in the form of a syllogism.

- The Three-Marked Sign (trirūpalimga): For a sign to be a valid basis for inference, it must possess three characteristics:

- Presence in the Subject (pakṣadharmatva): The sign must be present in the object of inference (the subject or pakṣa).

- Presence in the Similar Instance (sapakṣa): The sign must be present in cases that share the characteristic being inferred (the predicate or sadhya).

- Absence in the Dissimilar Instance (vipakṣa): The sign must be absent in cases that do not possess the characteristic being inferred.

- Types of Logical Reasons (Hetu): The text categorizes the valid logical reasons based on their relationship to the conclusion:

- Invariable Non-Perception (anupalabdhi): The absence of something that, if it were present, would be perceivable, indicating the absence of its cause or essential nature.

- Essential Nature (svabhāva): When a property is inherent to the very essence of the subject.

- Effect (kārya): When the effect is present, inferring the presence of its cause.

- The Concept of Perceived Absence (dr̥śyānupalabdhi): A significant portion of this chapter deals with the validity of inferring absence from the non-perception of something that should be perceivable if it existed. This is crucial for establishing negative conclusions. The text outlines eleven types of such perceived absence.

- The Role of the Unperceived: The text discusses how unperceived phenomena can be inferred, but emphasizes the importance of the logical connection (vyāpti) between the inferential sign and the inferential mark.

Chapter 3: Syllogisms (Parārthānumāna)

- The Nature of Syllogism: Syllogism is defined as the articulation of the three-marked sign (trirūpalimga). It is a linguistic act that leads to inferential knowledge.

- Two Forms of Syllogism: Syllogisms are presented in two main forms based on the inferential relationship conveyed:

- Sādharmya-vat (Argument by Similarity): Demonstrating the presence of the inferred quality by highlighting its co-presence with the sign in similar instances. This typically involves an affirmative statement.

- Vaidharmya-vat (Argument by Dissimilarity): Demonstrating the absence of the inferred quality by highlighting its co-absence with the sign in dissimilar instances. This typically involves a negative statement.

- The Argument from Absence (Anupalabdhi in Syllogisms): The text shows how arguments based on non-perception are formulated within the syllogistic structure.

- The Five Fallacies (Pancābhāsa): While the chapter focuses on valid inference, it also implicitly addresses fallacies by detailing the requirements for valid reasons. The Tika then explicitly discusses various fallacies that can arise in inference, including:

- Asiddha (Unestablished): When the middle term (the sign) is not established.

- Anaikāntika (Irregular/Contingent): When the middle term is not invariably connected to the major term (the predicate), appearing in both similar and dissimilar instances or being uncertain.

- Viruddha (Contradictory): When the middle term directly contradicts the predicate.

- Vyabhicārī (Erratic): (Though not explicitly listed as a separate term in the summaries provided, the concept of irregularity is covered under Anaikāntika).

- The text also discusses various forms of fallacies related to these categories, such as contradictory reasons, irregular reasons, fallacious reasons, and the role of the "erratic" reasoning.

- The Fallacy of the Unestablished: This fallacy occurs when the middle term itself is not proven to exist or is uncertain in its presence. This includes the fallacy of the unestablished subject (pakṣābhāsa), where the subject itself is questionable.

- The Fallacy of the Irregular Middle Term: This is a common fallacy where the middle term fails to establish a consistent relationship with the major term, appearing in contexts where the major term is present and absent.

- The Fallacy of the Contradictory Middle Term: This occurs when the middle term directly negates the major term.

- The Fallacy of the Unestablished Sign: This includes situations where the sign is not proven to exist in the subject or is uncertain.

- Fallacies in the Syllogistic Structure: The text also touches upon fallacies related to the entire syllogistic presentation, such as using a faulty example (dr̥ṣṭāntābhāsa) or presenting arguments that are logically unsound.

Editor's Contribution:

P. I. Tarkas, in his edition, likely provides critical notes, explanations of Sanskrit terms, and possibly an overview in English, making the complex philosophical arguments accessible to a wider audience. The errata listed indicate his meticulous work in ensuring the accuracy of the text.

Jain Connection:

While the Nyayabindu is a cornerstone of Buddhist logic, its inclusion in a Jain catalog and its subsequent commentary by Dharmottara (who, while primarily known in the Buddhist tradition, engaged with the broader Indian philosophical landscape) suggests a dialogue or comparative study between Buddhist and Jain epistemologies. Jain philosophy also has its own elaborate systems of logic and knowledge validation, such as the Pramāṇas (means of knowledge) like perception, inference, and testimony. This edition likely highlights the points of convergence and divergence between these traditions.