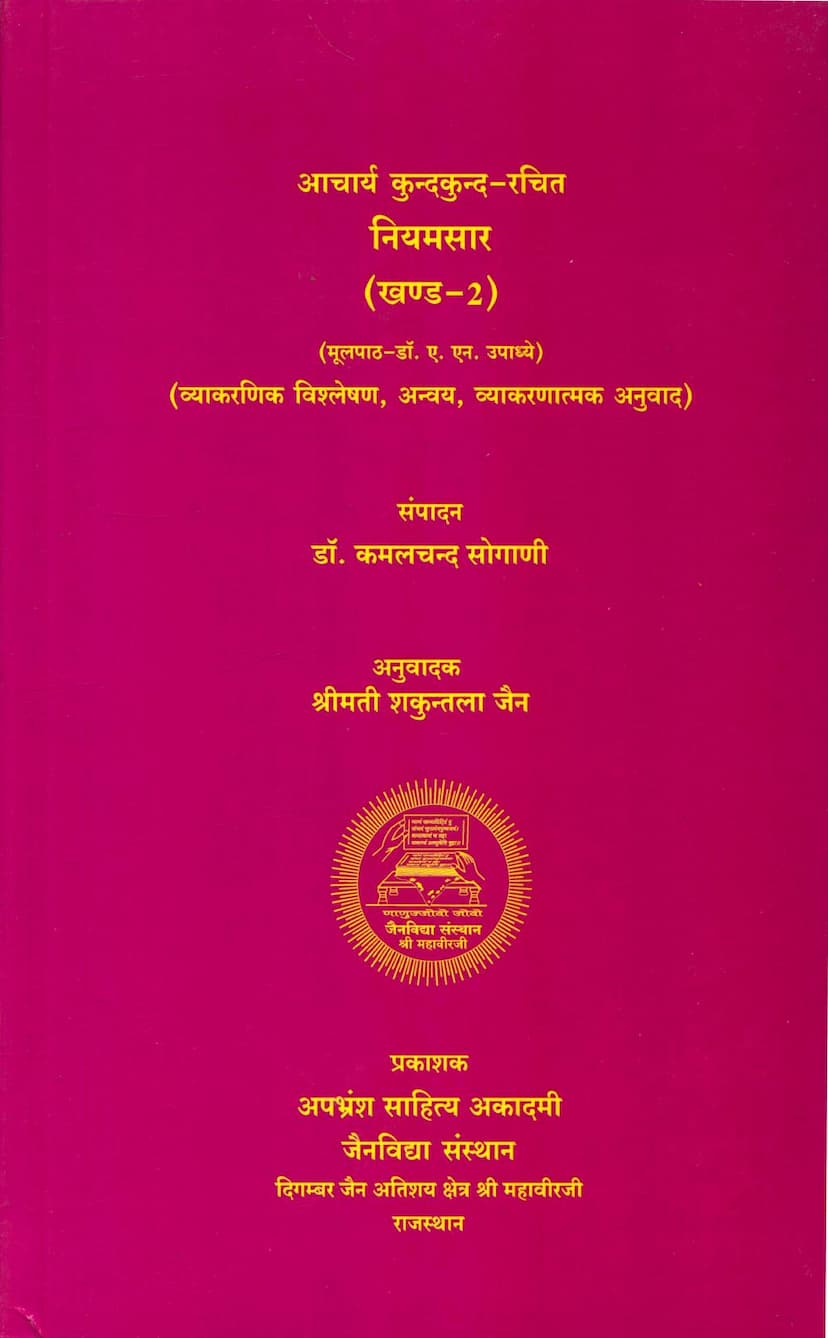

Niyamsara Part 02

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of Niyamsara Part 02 by Acharya Kundakunda, edited by Kamalchand Sogani and translated by Shakuntala Jain:

This volume, Niyamsara Part 02, is a significant work in Jain philosophy, offering a detailed exploration of spiritual practices and the path to liberation. It continues the teachings presented in Part 01, delving deeper into the essential principles for spiritual attainment as expounded by the revered Acharya Kundakunda.

Key Themes and Content:

The book is structured around several key "Adhikaras" (chapters or sections), each focusing on specific aspects of the spiritual journey:

-

Paramarthaprati-kramana-adhikara (Chapter on Supreme Repentance) (Gathas 77-94):

- This section emphasizes the understanding of the true self as distinct from transient states of existence like hellish, animal, human, and divine realms.

- It refutes the identification of the soul with various states of being, classifications, or physical attributes (age, etc.).

- The core message is that the self is not the doer, enabler, or approver of these external states.

- Prati-kramana (Repentance) is defined not merely by verbal utterances but as the internal process of renouncing attachment to passionate states (like attachment, aversion, delusion) and engaging in deep meditation on the pure soul. True repentance is achieved through self-awareness and the cessation of external activities, turning inward towards the soul.

- It highlights that genuine repentance is achieved by leaving the path of delusion and adhering to the path of Jina (the enlightened ones) through steadfast contemplation of the self.

- Meditation is presented as the supreme means to overcome all faults and achieve the goal of self-realization.

-

Nishchaya-pratyakhyana-adhikara (Chapter on Definitive Vow of Abstinence) (Gathas 95-106):

- This chapter focuses on Pratyakhyana (Vow of Abstinence) as a crucial step towards spiritual progress.

- It defines true Pratyakhyana as abstaining from all external verbal engagements and focusing on the meditation of the pure soul, thereby warding off future favorable and unfavorable mental states (options).

- The enlightened individual understands their true nature as one possessing infinite knowledge, perception, bliss, and power, and identifies solely with this pure self.

- This section stresses the importance of non-attachment (non-possession) and the renunciation of external objects, recognizing the soul as the sole refuge.

- The soul is presented as being beyond all modifications and states, and by meditating on this self, one achieves true restraint and abstinence.

-

Paramālocana-adhikara (Chapter on Supreme Confession) (Gathas 107-112):

- This part elaborates on Ālocana (Confession) as a means of purifying the self.

- True confession is described as the contemplation of the soul, which is free from the body, karma, and all deluded qualities and states.

- Four types of Ālocana are detailed:

- Ālocana: Seeing the soul by stabilizing the inner state in equanimity.

- Ālūṁchana: Uprooting the cause of defects.

- Viyaḍīkaraṇa: Expressing or revealing the pure virtues of the soul.

- Bhāvaśuddhi: Purification of the internal state by being free from desires, ego, deceit, and greed.

- The essence is the inner contemplation and purification of one's actions and thoughts.

-

Shuddha-nishchaya-prāyaścita-adhikara (Chapter on Pure Definitive Atonement) (Gathas 113-121):

- This section discusses Prāyaścita (Atonement) as the attainment of a tranquil and undisturbed mind.

- True atonement is achieved through the contemplation of the annihilation of passions like anger, pride, deceit, and greed, and the constant reflection on the soul's own pure qualities.

- The text emphasizes that the rigorous spiritual practices (tapas) undertaken by great ascetics, both external and internal, are the cause of the destruction of various karmas.

- It asserts that by relying solely on the nature of the self, one can abandon all outward-focused tendencies, and this complete renunciation is accomplished through meditation.

- The practice of meditation leads to right faith, right knowledge, and right conduct.

-

Paramasamādhi-adhikara (Chapter on Supreme Equanimity) (Gathas 122-133):

- This chapter focuses on Samādhi (Equanimity) as the state of supreme peace and concentration.

- It defines supreme equanimity as achieved by abandoning the activity of verbal articulation and meditating on the soul with a passion-free mind.

- The text states that external practices like living in forests, enduring physical hardships, fasting, studying, and maintaining silence are of no benefit to an ascetic devoid of equanimity and meditation.

- Equanimity is attained by one who is free from all sins, controls the three modes of action (mind, speech, body), and has mastered their senses.

- It highlights that equanimity is realized by those who turn away from worldly affairs and whose pure self is inwardly present in their conduct, rules, and austerities.

- The importance of meditating on Dharma and Shukla Dhyana (higher forms of meditation) is stressed for achieving equanimity.

-

Paramabhakti-adhikara (Chapter on Supreme Devotion) (Gathas 134-140):

- This section explores Bhakti (Devotion) as an essential element in the spiritual path.

- It defines devotion to Nirvana (liberation) as practiced by lay devotees (Shravaka) and ascetics (Shramana) who have faith in right faith, right knowledge, and right conduct.

- Through this devotion, the soul attains its inherent, independent qualities.

- The text emphasizes that the practice of Yoga-devotion (devotion through contemplative practices) is crucial.

- It highlights that by renouncing desires and external attachments, and by dwelling in the pure self, one becomes devoted to yoga.

- The example of Rishabha and other Tirthankaras is given, who achieved supreme devotion and attained liberation.

-

Nishchaya-paramāvasyaka-adhikara (Chapter on Definitive Supreme Necessity) (Gathas 141-158):

- This part discusses Āvasyaka (Necessity or Essential Duty), which is identified as the practice of meditation.

- It clarifies that one who is not under the control of others has meditation as their essential duty. Meditation is the yogic practice that leads to the destruction of karma and is described as the path to Nirvana.

- The text contrasts those who are influenced by external affairs (Bahi-ratma) with those who are inwardly focused (Antar-ratma). The latter are considered self-controlled and are capable of essential meditative practices.

- It is stated that engaging in external and internal dialogues makes one extroverted, while refraining from them makes one introverted and self-controlled.

- The importance of contemplating the self rather than being engrossed in the nature of substances, qualities, and modifications is stressed.

- The true seeker who meditates on the pure, unblemished self, free from external influences, truly attains mastery over the self and performs the essential duty.

- The chapter defines the practice of the "essential duty" (meditation) as the path to achieving one's true nature and attaining the state of a Shramana (ascetic).

-

Shuddhopayoga-adhikara (Chapter on Pure Consciousness) (Gathas 159-187):

- This final section focuses on Shuddhopayoga (Pure Consciousness), the ultimate state of liberation.

- It explains that the omniscient Tirthankaras (Kevali) know and see everything through their pure consciousness.

- The text elaborates on the nature of knowledge and perception, stating that they are simultaneous and inseparable, much like the sun's light and heat.

- It distinguishes between external (vyavahara) and internal (nishchaya) perspectives, explaining how knowledge encompasses both self and others.

- The omniscient state is described as the simultaneous presence of infinite knowledge, perception, bliss, and energy.

- The text emphasizes that while the omniscient being knows all phenomena, their actions are not motivated by desire, thus they do not incur karma.

- The chapter culminates in the description of the Siddha state: liberated souls who have shed all karma, are free from birth, old age, and death, possess infinite knowledge, perception, bliss, and power, are eternal, immutable, and free from suffering.

- Finally, it encourages renouncing debates on spiritual doctrines due to the diverse nature of beings, their karmas, and their attainments.

Key Principles Highlighted:

- Self-Reliance and Inner Focus: The paramount importance of turning inward and meditating on the soul is consistently emphasized throughout the text.

- Distinction between Self and Non-Self: A clear distinction is maintained between the eternal, pure soul and the transient physical body, karmas, and external states of existence.

- Meditation as the Path: Meditation is presented as the central practice for achieving repentance, abstinence, confession, atonement, equanimity, devotion, and ultimately, liberation.

- Renunciation of Passions: Overcoming desires, attachments, aversions, and other passions is crucial for spiritual progress.

- The State of Kevalis and Siddhas: The book provides profound insights into the characteristics and experiences of omniscient beings and the perfectly liberated souls.

Translation and Editing:

The book is lauded for its clear and accessible Hindi translation, making the profound teachings of Acharya Kundakunda comprehensible to a wider audience. The grammatical analysis, synoptic arrangement of words (Anvaya), and detailed explanations contribute significantly to understanding the Prakrit text. The editors and translators are commended for their diligent work in making this complex philosophical treatise accessible for study.