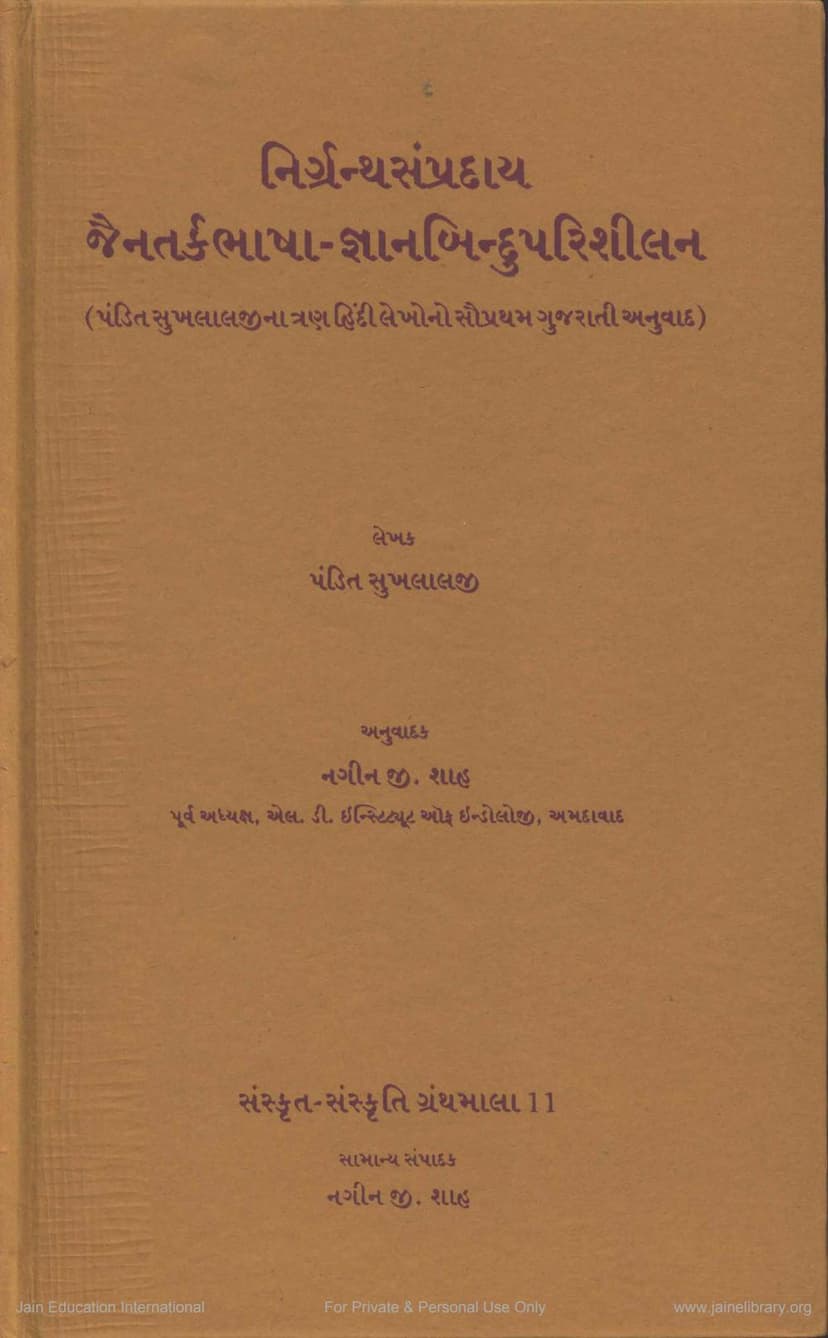

Nirgranthasampraday Jaintarkbhasha Gyanbinduparishilan

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

This is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Nirgranthasampraday: Jaintarkbhasha Gyanbinduparishilan" (A Study of the Nirgrantha Tradition: Jaina Logic, Knowledge Bindu) authored by Sukhlal Sanghavi and translated by Nagin J. Shah.

The book is a Gujarati translation of three Hindi essays by the renowned Jain scholar Pandit Sukhlalji. It was published by Dr. Jagruti Dilip Sheth as part of the Sanskrit-Sanskriti Granthamala series, edited by Nagin J. Shah.

The work is divided into three main chapters:

Chapter 1: The Nirgrantha Tradition (નિર્ગ્રન્થ સંપ્રદાય)

This chapter provides an introduction to the Shraman Nirgrantha (Jain) religion. It delves into the historical perspective and analyzes the value of this approach.

- Introduction to Shraman Nirgrantha Dharma: The text defines the Shraman tradition as a movement that opposed the Brahmanical/Vedic tradition. It highlights that various Shraman branches like Sankhya, Jainism, Buddhism, and Ajivika existed, with Jainism and Buddhism being the most prominent and surviving ancient traditions. The author emphasizes that the study aims to shed historical light on the ancient form of Jainism, specifically from the time of Bhagwan Parshvanath (800 BCE) to the time of Ashoka.

- Self and Other Beliefs and Historical Perspective: The importance of historical perspective is stressed to remove dogma and foster an "anekant" (multi-faceted) viewpoint, promoting amity and understanding between sects. It argues that faith and devotion born from ignorance and delusion are blind faith, while faith based on knowledge and intellect is true faith.

- Historical Evaluation of Perspective: The text acknowledges that foreign scholars' views have introduced doubts about traditional beliefs, even among those with traditional upbringing. It emphasizes that historical facts are crucial for proving the truth of any belief. Historical perspective is presented as the sole tool to bridge the gaps created by ignorance, illusion, and superstition between different communities.

- Historical Place of Agamic Literature: The author explains the necessity of examining the scriptures using external evidence. If external sources support the Agamic statements, then the Agamic parts are considered authentic. Historical examination forces those who reject the Agamas to accept their relative authority and educates those who accept them blindly to do so with discernment.

- Relationship between Jain and Buddhist Agamas: The text notes the strong connection between Jain and Buddhist scriptures, due to both being Shraman traditions and their founders, Mahavira and Buddha, being contemporaries and active in similar geographical areas. Their disciples interacted, debated, and sometimes even followed both figures. Buddhist scriptures extensively describe Jain practices and beliefs, even if critically.

- Buddha and Mahavir: A key distinction is made between Buddha, who rejected existing ascetic and yogic traditions to establish a new path, and Mahavir, who refined and purified an existing tradition inherited from his lineage. The text highlights Buddha's critique of various contemporary sects, including the Nirganthas, while Mahavir often reconciled his reforms with the existing Pasrshvanath tradition.

- Influence of Nirgrantha Tradition on Buddha: The text notes that Buddha, before establishing his own path, had a period of ascetic practice which likely included some time within the Nirgrantha tradition, possibly following Parshvanath. Buddha's critique of Nirgrantha practices, especially intense asceticism, is discussed.

- Key Aspects of Ancient Practices and Beliefs: The chapter then lists and discusses several key aspects of ancient Jain practices and beliefs as found in Buddhist texts:

- Dietary Practices (Meat-based vs. Vegetarian): This is a major focus, discussing historical debates and controversies within Jainism regarding the consumption of meat. The text notes that even ancient Jain ascetics might have consumed meat, a view supported by some interpretations of ancient texts and scholarly debate. It traces historical movements and interpretations regarding this issue.

- Unclothedness (Asceticism) vs. Clothedness: The practice of nudity among ascetics is discussed, contrasting it with the practice of wearing clothes.

- Asceticism (Tapas): The importance and intensity of ascetic practices in Jainism are highlighted, noting that it became almost synonymous with Jainism.

- Conduct and Ethics (Achar-Vichar): General principles of Jain conduct are touched upon.

- Chaturyama: This refers to the four vows, which are discussed in relation to their ancient form.

- Uposatha-Pausadha: The practice of fasting and religious observance, similar to the Buddhist Upasatha, is examined.

- Language and Speech (Bhasha-Vichar): The importance of controlled and ethical speech is mentioned.

- Tridanda: This refers to the three restraints (mind, speech, body).

- Leshya: The concept of karmic dispositions affecting one's color or aura.

- Omniscience (Sarvajnatva): The belief in omniscience is discussed.

Chapter 2: A Study of Jaina Tarkabhasha (જૈન તર્કભાષાનું પરિશીલન)

This chapter focuses on the book "Jaina Tarkabhasha" and its author, Upadhyaya Yashovijayji.

- Author (Granthakar): The text provides a detailed biography of Upadhyaya Yashovijayji, highlighting his birth in Kano village (Gujarat), his initiation into Jainism by Pandit Nayavijayji, his rigorous studies in Kashi and Agra in logic and other Vedic philosophies, and his eventual recognition as an 'Upadhyaya'. His scholarly pursuits and dedication to textual study and analysis are emphasized.

- The Work (Granth): The author discusses the genesis of Yashovijayji's decision to write "Jaina Tarkabhasha." Influenced by the works of Buddhist scholar Mokshakar and Vedic scholar Keshavamishra, Yashovijayji aimed to create a text that presented Jain philosophical tenets in a logical framework, particularly in the context of the "Navya Nyaya" (New Logic) movement. The choice of the title "Tarkabhasha" is explained in relation to its predecessors and the Jain tradition of naming texts with "Tarka." The structural influence of Mokshakar's "Tarkabhasha" and the thematic influence of Bhattarak Akalanka's "Laghiyastraya" on Yashovijayji's work are analyzed. The author notes that Yashovijayji synthesized existing Jain knowledge with contemporary logical methodologies, presenting a comprehensive analysis of Jain logic, the concept of 'Naya' (standpoints), and 'Nikshepa' (classification).

Chapter 3: A Study of Gyanbindu (જ્ઞાનબિન્દુનું પરિશીલન)

This chapter delves into the work "Gyanbindu" and its author, Upadhyaya Yashovijayji.

- Author (Granthakar): This section refers back to the biographical details provided in the previous chapter, as the author is the same.

- External Form of the Work:

- Name: The name "Gyanbindu" (Drop of Knowledge) is explained. The author, Yashovijayji, uses this name to suggest that while the text contains profound knowledge, it is but a drop from the vast ocean of scriptural knowledge and his own prior extensive work, "Gyanarnava." The use of "Bindu" in titles is traced to a tradition in various Indian philosophical schools (Buddhist, Vedic, Jain), with specific examples like Dharmakirti's "Hetubindu" and "Nyayabindu," Vachaspati Mishra's "Tattvabindu," Madhusudan Saraswati's "Siddhantabindu," and Haribhadra Suri's "Yogabindu" and "Dharmabindu." Yashovijayji's "Gyanbindu" is presented as a continuation of this tradition, with a unique contribution in the "Gyanarnava" and "Gyanbindu" pairing.

- Subject Matter (Vishay): The text highlights the central theme of knowledge, its various types, and its acquisition. It notes the ancient Jain belief in five types of knowledge (Mati, Sruta, Avadhi, Manahparyaya, Kevala), tracing their roots back to pre-Mahavir Jain traditions. The author discusses the development of these concepts, noting influences from other Indian philosophical schools.

- Style of Composition (Rachna Shaili): The author describes the composition style as 'Varnan Shaili' or 'Prakaran Shaili,' meaning it's a direct exposition of the subject matter rather than a commentary on a pre-existing work. This style is compared to that of Vidyarananda's "Pramana Pariksha," Madhusudan Saraswati's "Vedanta Kalpalatika," and Sadananda's "Vedanta Sara."

- General Discussion of Knowledge:

- Definition of Knowledge: The Jain definition of knowledge as an attribute of the soul, illuminating both the self and others, is presented. This is compared to other Indian philosophical traditions, particularly Sankhya/Vedanta and Buddhism/Nyaya.

- States of Knowledge (Complete vs. Incomplete) and their Causes: The text explains that knowledge can be complete or incomplete due to karmic obstructions. The primary obstruction is Kevala-jnana-avarana Karma (knowledge-obscuring karma).

- Nature of Knowledge-Obscuring Karma: The author discusses the nature of this karma, comparing it to dense clouds obscuring the sun. It's argued that while it obstructs complete knowledge, it can also be the cause of incomplete knowledge.

- Resolving the Contradiction of "Covered and Uncovered" in One Substance: This refers to the Jain concept of how the soul can be simultaneously covered by karma (incomplete knowledge) and yet possess its inherent nature (consciousness). The author explains this using the anekanta perspective, differentiating between substance (dravya) and mode (paryaya).

- Unsuitability of "Covered and Uncovered" in Vedanta: The text critiques the Vedanta concept of the soul's covered and uncovered states, finding it inconsistent with their absolute monistic view.

- Hierarchy and Cessation of Incomplete Knowledge: The text explains the graded levels of incomplete knowledge and the causes and processes for overcoming them.

- Process of 'Kshayopashama': This crucial Jain concept describes the partial destruction (kshay) and partial subsidence (upashama) of karmas, leading to the manifestation of partial knowledge.

- Discussions on Mati and Sruta Knowledge: This section details the distinction between Mati (sense-based and mental knowledge) and Sruta (scriptural knowledge), exploring their interrelationships, historical development of their definitions, and the evolution of understanding their scope.

- Discussions on Avadhi and Manahparyaya Knowledge: These are types of clairvoyant and telepathic knowledge, respectively, and their nuances are explored.

- Discussion on Kevala Knowledge: This is the most extensive part, covering the existence, nature, causes, and implications of Kevala-jnana (omniscience). It includes discussions on the relationship between knowledge and perception, the nature of omniscient causation, the role of passions (ragadi dosha) and karma, the critique of atheistic philosophies (Nairatmya), the interpretation of Vedic scriptures in a Jain context, and the historical debates surrounding the precise distinction and relationship between Kevala-jnana and Kevala-darshana (omniscience and omni-perception).

Overall Themes and Significance:

The book, through its detailed analysis of Pandit Sukhlalji's essays, aims to provide a scholarly and historical understanding of the Nirgrantha (Jain) tradition. It emphasizes the importance of historical perspective in understanding religious doctrines, the intellectual rigor within Jain philosophy, and the ethical dimensions of Jainism, particularly its profound emphasis on ahimsa (non-violence). The discussions on logic, knowledge, and epistemology highlight the sophisticated philosophical underpinnings of Jainism and its engagement with other Indian philosophical traditions. The translator, Nagin J. Shah, through his extensive knowledge and careful presentation, makes this complex philosophical inquiry accessible to Gujarati readers.