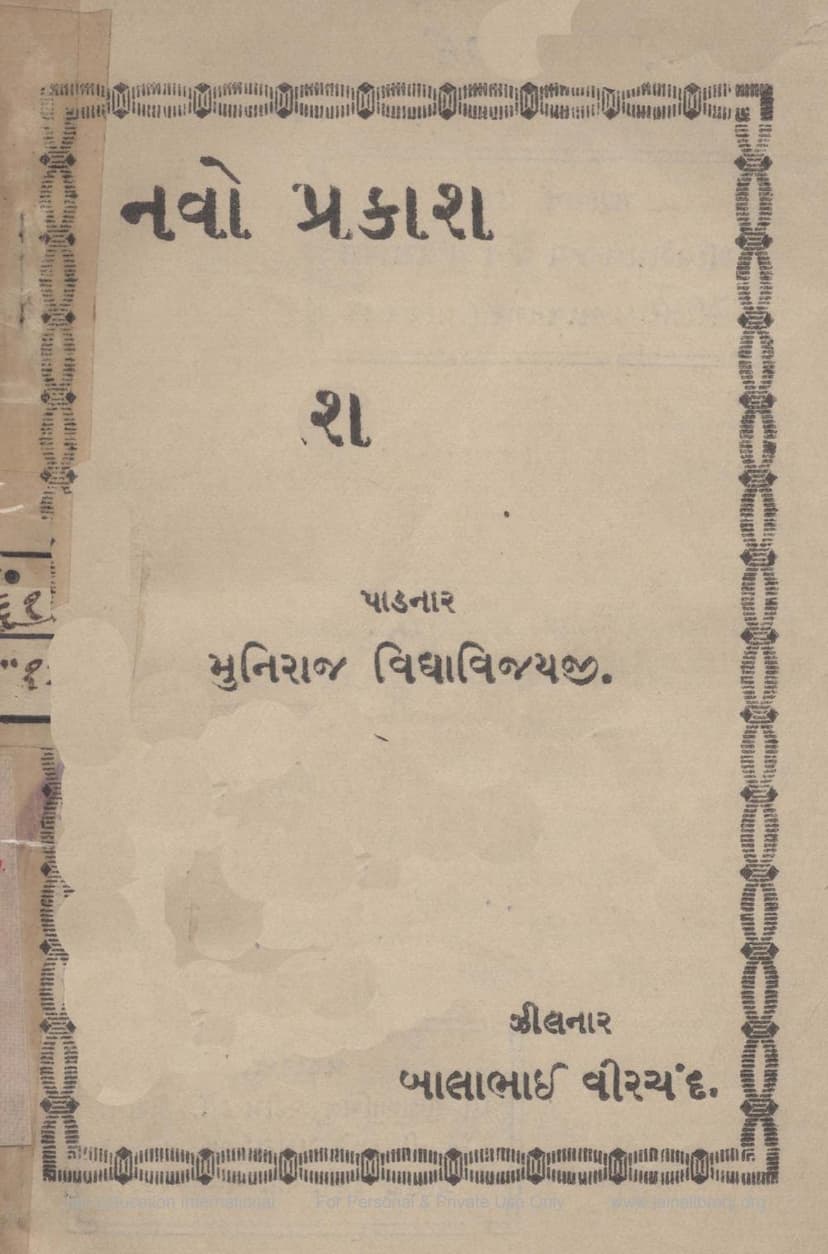

Navo Prakash

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Navo Prakash" by Vidyavijay, based on the provided pages:

The book "Navo Prakash" (New Light) is a collection of questions and answers, featuring the thoughts and opinions of Muniiraj Shri Vidyavijayji Maharaj, a prominent Jain monk known for his reformist ideas, writing, oratory skills, and active participation in social and religious activities. The book was published by Balabhai Virchand Desai and printed by The Luhana Mitra Steam Pre. Press in Vadodara on May 5, 1929.

The author of the book, Balabhai Virchand Desai, states his intention to present Muniiraj Vidyavijayji's views to the Jain community to address what he perceives as a "terrible wildfire" within the community. He explains that he took the Muniiraj's valuable time to get answers to several questions, which are presented verbatim in the book, with the hope that the Jain society will gain much from them and implement the suggested path for significant improvement.

The book then proceeds with a series of questions posed to Muniiraj Vidyavijayji, covering various aspects of Jainism and the Jain community:

1. Jain Literature: Muniiraj Vidyavijayji believes Jain literature is excellent, vast, and comprehensive, earning admiration from European scholars. He emphasizes the need for its wider propagation, suggesting that institutions like Jain Conferences, Anandji Kalyanji Pedhi, and Jain Associations of India, as well as wealthy individuals, should establish scholarships and encourage the writing of literature that appeals to both Jains and non-Jains. He criticizes the current trend of writing devotional songs or highly philosophical books that remain unsold, advocating for a style that combines faith with generosity and timeliness, and engaging the reader with fresh insights for the modern era.

2. Life of Mahavir: He feels that no adequate biography of Mahavir has been written that would be useful to both Jains and scholars. He highlights the need for a well-researched and beautifully written biography from a historical perspective, acceptable to the world, requiring significant resources, scholarly intellect, and time. He mentions an article in Amrut Vachan that touches upon this and hopes an organization or wealthy individual will take up this cause.

3. Jain Newspapers: Muniiraj Vidyavijayji expresses doubt about calling many current Jain newspapers truly newspapers. He criticizes their lack of journalistic principles, clear objectives, and understanding of journalistic duties. While acknowledging their usefulness in conveying religious events and the movements of monks and nuns, he stresses the need for journalists to be generous, true well-wishers of society, impartial, and well-versed in literature. He laments that mere ability to hold a pen makes someone a journalist, and the state of Jain newspapers will not improve until this changes. He also points out that the harm caused by these newspapers often outweighs their benefits, contributing to instigation and strong partisanship within the community. He insists that journalists should appear neutral and impartial.

4. Organization of Jain Monks: He reiterates his earlier writings on this topic, stating that the improvement of the entire Jain community depends on the organization of Jain monks. He criticizes the internal conflicts, slander, and incitement among monks, which are diminishing the value of the monastic institution. He warns that when societal faith in monks wanes, it will be difficult for the community to distinguish between good and bad monks, leading to a severe crisis. He also blames some influential laypeople who have "bought over" certain monks, turning them into their "toys." He believes that although monastic organization seems impossible, it will happen eventually, and that "extreme fall is an indicator of rise."

5. Initiation (Diksha): He addresses the division in opinions regarding initiation. He states that those who increase the number of monks through unqualified initiations are reducing the value of the monastic institution. He points out that many monks leave their vows and their actions bring disgrace to the entire monastic community, leading to unfair criticism from non-Jains. He attributes this to unqualified initiations and the lack of monastic organization, urging monks to prioritize organizing themselves and addressing the issue of initiation.

6. Status of Householders vs. Monks: As a monk, he desires an increase in the monastic community but stresses that this is only possible if the "mine" from which these gems are extracted – the householder stage – is well-reformed. He criticizes the current state of householders, describing them as corrupt, weak, cowardly, and deviated from their duties. He questions what value such individuals can bring to the monastic life. He argues that monks should focus on improving the condition of householders, guiding them in their duties. Well-trained, detached, and duty-conscious householders can produce better monks than five weak ones. He emphasizes the need for householders to understand their duties towards parents, spouses, society, religion, and the country, and laments that a lack of proper guidance from preachers has made the Jain populace weak and fearful. He calls for a return to "heroism" as a primary virtue for Jain householders.

7. Rituals like Ujman and Upadhan: He sees little benefit in these rituals when performed for outward fame and without considering time, place, and financial capacity. He believes that in the current circumstances of the Jain society, wealthy individuals should undertake more essential charitable works. He points out that with a declining population, wealthy individuals and monks should not engage in activities without considering the circumstances. He advocates for focusing on crucial needs like providing food, education, and support for widows, rather than ostentatious rituals. He highlights the plight of thousands lacking basic necessities, students unable to pursue education, widows suffering due to societal customs, and young men being forced to convert due to lack of opportunity. He calls for wealthy individuals to support institutions like vocational schools and widow shelters, lamenting that many such institutions struggle due to a lack of funds. He notes a recent positive trend of some wealthy individuals showing concern for education and essential works.

8. Discussion on Temple Property (Devdravya): His views remain the same. He believes that the collection of temple property should be standardized and that redirecting its income to ordinary accounts would be beneficial for society. He acknowledges that the discussion on temple property has yielded positive results, with many villages amending their customs. He observes that the younger generation is challenging outdated and superstitious practices, and that ultimately, the new ideas will prevail.

9. Monks' Participation in National Activities: He believes that monks involved in social, national, and religious activities cannot ignore the current state of the nation. They should inspire patriotism through their teachings, promote love for indigenous products, and encourage their use. He states that this does not harm their monastic vows. However, he stresses that this requires personal example – clean living and then preaching. Monks should practice abstinence from impure food and women themselves before preaching to the public.

10. Faith in Reformers: He has expressed his views on this multiple times. He categorizes reformers into three types: the poor/ordinary with pure intentions but lacking the means, the educated who are often driven by self-interest and fame, and the wealthy who become reformers to gain public attention. He notes that wealthy reformers spend generously on their causes, but often, the financially struggling reformers feel discouraged due to a lack of support. He urges all three categories of reformers to engage in reform work with body, mind, and wealth, abandoning luxury and empowering young people with courage and financial support when needed.

11. Inter-dining and Marriage with Non-Jains: He states that Jain principles do not prohibit this. Under the guidance of Bhagwan Mahavir, all humans, regardless of caste, creed, or country, should be treated with complete openness. He believes that their current narrow-mindedness is reducing the number of Mahavir's followers. He advocates for shedding this narrowness and embracing anyone who adheres to Jain principles and practices, which will undoubtedly increase the number of Jain followers. He is optimistic that this liberality will prevail in the next twenty-five years.

12. Widow Remarriage: He acknowledges this as a national issue, exacerbated by child marriages and marriages with old men, leading to an increase in widows. He criticizes the lack of support systems for widows and the ill-treatment they face. He notes that the question of widow remarriage has been raised, with the Digambar sect taking the lead. He anticipates that the Shvetambar sect will also soon address this issue, and that while outright permission might be resisted, reformers will consider this difficult question. He emphasizes that the root causes of widowhood must be addressed, and if societal restrictions are not reformed, nature will take its course.

13. Theist vs. Atheist Debate: He hasn't read recent debates on this topic. However, based on what he has read, he finds no value or benefit for society in the discussion. He criticizes Sagarji for escalating a personal comment by Shri Vijayvallabh Suriji, stating that calling someone an atheist does not diminish their piety or work. He describes Sagarji's approach as one of igniting fires through speech. He disagrees with Shri Vijayvallabh Suriji's silence on Sagarji's accusations, stating that a true reformer should either publicly admit or deny such statements. He believes honesty in presenting facts is crucial. He also devalues scholastic debates in the current era, considering them as a means for ordinary people to showcase bravery.

14. Monks' Association with Institutions: He welcomes the presence of monks in educational institutions that offer independent curricula. He highlights that monks have no financial self-interest and their virtuous character can significantly influence children. He advocates for learned monks to take responsibility for studying justice and scriptures, suggesting that even if it requires a temporary deviation from their usual routine, it would be beneficial. He believes that such monks can effectively guide students, making them good citizens and selfless servants of society. He emphasizes that instead of monks moving in groups, they should be assigned suitable roles by their leaders, utilizing their knowledge and intellect for the benefit of children.

15. Teaching Youth Skills (Shastra Adi): He refers to the 64 arts for women and 72 arts for men mentioned in Jain scriptures. He believes householders should learn all these arts for the protection of themselves, their families, property, country, and religious places. He states that a householder never knows when they might encounter difficult situations, so acquiring defensive skills is essential. He distinguishes between religious rules and the practicalities of managing a household. He cites examples of Jain kings and ministers engaging in warfare to protect their kingdoms and people.

16. Unity Among Jain Sects: He considers complete unity among the three sects as impossible but advocates for maintaining peace. He proposes establishing a society of respected leaders from all three sects. Each member should work as a Jain, an follower of Mahavir, striving to create peace within their own sect and resolving current disputes with the consent of other respected householders from their sect. He also suggests showing mutual sympathy and understanding in areas of agreement to improve the overall atmosphere.

17. The Institution of Sadhvis (Nuns): He reflects on the current state of Sadhvis, especially after observing Dr. Kruz (Sumbhadra Devi) embracing Shravak vows. He notes that while he has been away from regions with large numbers of Sadhvis, he has heard disturbing accounts of harsh treatment of disciples. He believes many Sadhvis become nuns out of ignorance and a sorrowful detachment from worldly life. He suggests temporarily suspending female initiations and focusing on reforming the existing institution. He questions how many Sadhvis are educated and capable of giving lectures. He laments the negative impression created by some Sadhvis who wander in markets and their lack of purpose. He is particularly concerned when learned women like Sumbhadra Devi ask for role models and he struggles to recommend anyone who wouldn't make them regret their decision. He believes that educated, disciplined, and well-managed Sadhvis could reform the entire Jain women's community and, consequently, the Jain society. He urges Jain women to strive to improve their own circumstances.

18. Activities of Shri Ramvijayji and Sagarānanda Suri: He considers this a personal question and avoids making a judgment that could be perceived as biased. However, he states that it's impossible for all activities to be solely beneficial or harmful. He believes that a significant portion of their activities are undertaken without considering time, place, and financial capacity, and are driven by a desire for self-praise and recognition from their community. He feels that some of their actions have caused shame not only to themselves but also to the Jain society. Many believe they contribute to the current "wildfire" within the Jain community. While they possess abilities, many feel these abilities are being misused. He even speculates that they might be an obstacle to the organization of the entire monastic community, acknowledging that he might be mistaken in this opinion.

19. Response to Criticisms: He asserts his consistent approach of engaging in debates when there are differences of opinion. He believes in letting those who attack character rather than engage in intellectual discourse, or those who incite others from behind the scenes, continue their actions without stooping to their level. He views criticism and praise as natural human tendencies and advises not to be swayed by them. He states that even prominent figures like Muhammad, Jesus Christ, Buddha, and Mahavir were not spared from criticism. He is aware of the reasons behind the recent criticisms against him and his community, but he considers character attacks as cowardly and deserving of pity rather than punishment. He reiterates his belief that those who abandon monasticism for household life due to their inability to conquer worldly desires often criticize the entire monastic institution. Similarly, those excommunicated or expelled from institutions often malign them. He believes such criticism does not harm the parent institution or community. He acknowledges that temporary agitation is a sign of weakness, and getting agitated by minor disturbances is a mistake. He emphasizes the importance of relying on one's truthfulness, as adversities are not obstacles but rather the fragrance of one's virtuous actions. He provides examples of institutions that gained prominence and success through facing challenges. He concludes by sharing a principle for his life:

"Whether respected or not, we have no concern. Whether fruits are obtained or not, we have no desire to know. This life is for performing duty, day and night, immersed in it; To be free from debt to the world, duty must be done here."

The book concludes with the date and location of this recording: Shivpuri (Gwalior), Chaitra Sud 13 (Mahavir Janmadin), Veer Samvat 2455, Dharma Samvat 7.