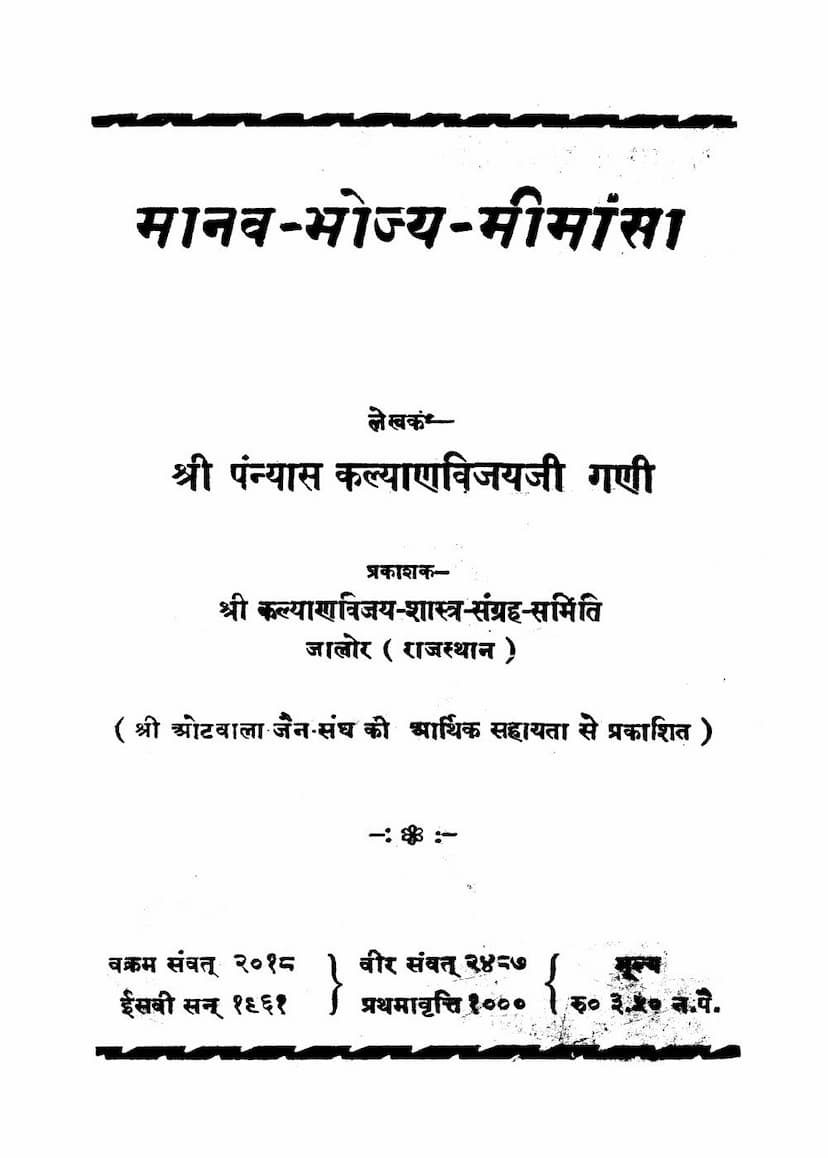

Manav Bhojya Mimansa

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

This is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Manav Bhojya Mimansa" (Human Diet Inquiry) by Kalyanvijay Gani, as derived from the provided text:

Book Title: Manav Bhojya Mimansa (मानव भोज्य मीमांसा) Author: Kalyanvijay Gani (कल्याणविजय गणी) Publisher: Kalyanvijay Shastra Sangraha Samiti (कल्याणविजय शास्त्र संग्रह समिति)

Overall Purpose: The book aims to provide a scholarly inquiry into the appropriate diet for humanity, drawing upon Jain scriptures, Vedic traditions, and scientific understanding. It seeks to counter the notion that meat consumption is necessary or beneficial for humans and argues for a vegetarian lifestyle based on ancient wisdom and modern evidence.

Key Themes and Arguments:

-

Human Diet is Naturally Vegetarian: The author asserts that, based on Jain scriptures, Vedic principles, and scientific reasoning, humans have historically been and should continue to be vegetarian. The text emphasizes that the natural design of the human body, including teeth, jaw structure, and digestive system, is more suited for a vegetarian diet.

-

Historical Context of Diet:

- Ancient Jain Times: It describes the diet in the early stages of the current era (Avasharpini Kalpa) as being based on fruits from wish-fulfilling trees. As these declined, humans progressively adopted fruits, roots, leaves, and later grains. The text traces the evolution of diet through different eras and the role of "Kulakars" (progenitors/lawgivers) in guiding human sustenance.

- Vedic Era and Sacrifices: The book delves into the interpretation of Vedic sacrifices. It argues that early Vedic sacrifices (Rig Vedic period) were primarily vegetarian, involving grains like barley (yava) and rice (brihi). It contends that the introduction of animal sacrifice and the misinterpretation of Vedic texts (due to the loss of the Nighantu and Nirukta) led to confusion and the eventual inclusion of animal sacrifice in later Vedic literature (Yajurveda, Shatapatha Brahmana). However, it highlights that even in later periods, animal sacrifice was limited to specific rituals and gradually disappeared.

- Jain Scriptures and Terminology: A significant portion of the book is dedicated to clarifying the meaning of terms like "mansa" (flesh/meat), "matsya" (fish), "pudgal" (matter), and "amisha" in Jain scriptures. The author argues that in ancient Jain texts, these terms often referred to specific edible plant parts, sweet preparations, or refined food items, rather than animal flesh. The evolution of these words and their later association with animal flesh due to increased meat consumption is discussed.

-

Critique of Meat Consumption:

- Scientific Arguments: The author cites numerous scientific and medical opinions, including those of professors and doctors, to highlight the detrimental effects of meat consumption on human health. These include links to cancer, tuberculosis, indigestion, joint diseases, anger, and the general weakening of the body. The anatomical differences between humans and carnivorous animals are also emphasized.

- Moral and Ethical Arguments: The text strongly advocates for Ahimsa (non-violence) as the highest principle, which naturally extends to a vegetarian diet. It critiques the violence inherent in meat production and consumption.

- Historical Misinterpretations: The author criticizes the misinterpretation of ancient texts that led to the justification of meat-eating.

-

Role of Jain Ascetics (Shramanas): The book extensively details the strict lifestyle and principles of Jain monks (Shramanas). It covers:

- Qualities for Monasticism: Rigorous requirements for aspiring monks, including age, physical and mental health, freedom from debt, and absence of servitude.

- Monastic Practices: The stringent rules regarding diet (Madhuakri Vriti - begging for alms from various households without prior arrangement), conduct, clothing (minimal and simple), use of only essential utensils, and the strict adherence to Ahimsa in every action.

- Types of Monks and their Rules: Discussion on different categories of monks (e.g., Jinakalpika, Sthavirakalpika) and their varying levels of austerity and possessions.

- Tapasya (Austerities): A detailed explanation of various rigorous penances and fasting practices undertaken by Jain monks for spiritual purification and karma reduction.

- Paryushana Parva: The practice of observing periods of intense fasting and austerity.

- Samlekhana: The voluntary cessation of eating and drinking at the end of life as a final spiritual discipline.

-

Comparison with Other Traditions:

- Vedic Tradition: While appreciating the core vegetarian principles found in early Vedic texts, the author critiques the later introduction of animal sacrifice and the justification of meat consumption by some Vedic scholars.

- Buddhism: The text discusses the evolution of Buddhist practices, noting that while Buddha emphasized non-violence, the later Buddhist tradition, especially in some regions, became more lenient towards meat consumption. The author highlights the potential for exaggeration in Buddhist scriptures and the deviation from Buddha's original teachings, particularly regarding diet. The criticism of meat consumption within Buddhism is also presented.

-

Critique of Erroneous Interpretations: The author addresses and refutes the interpretations of scholars like D.D. Kosambi and Hermann Jacobi who, based on selective readings of scriptures, suggested that Jain monks and early Vedic Brahmins consumed meat. The text provides counter-arguments and contextualizes these scriptural passages to demonstrate their non-literal or specific meanings.

-

Linguistic and Textual Analysis: The book engages in detailed etymological analysis of various Sanskrit and Prakrit words related to food and substances, demonstrating how their meanings have evolved or been misinterpreted over time.

Structure of the Book: The book is divided into six chapters, each exploring a specific aspect of the human diet inquiry:

- Chapter 1: Human Natural Diet: Discusses the inherent vegetarian nature of humans based on Jain, Vedic, and scientific perspectives.

- Chapter 2: Early Vedic Sacrifices: Examines the nature of Vedic sacrifices, arguing for their original vegetarianism and the later introduction of animal sacrifice.

- Chapter 3: Decision on the Meaning of "Meat": Focuses on the linguistic analysis of terms like "mansa" and "amisha" in Jain and Vedic literature, arguing for their original non-animal flesh meanings.

- Chapter 4: Jain Ascetics as Pure Food Eaters: Details the rigorous lifestyle, vows, practices, and austerities of Jain monks, emphasizing their pure vegetarianism and non-violence.

- Chapter 5: Non-Violent Vedic Ascetics (Parivrajaka): Explores the life and principles of Vedic renunciates (Vanaprasthas and Sannyasins), highlighting their adherence to simple living and vegetarianism, and critiquing later deviations.

- Chapter 6: The Shaakya Monk (Buddhist Monk) as a Receiver of Commanded Food: Discusses the history of Buddhism, its dietary practices, the evolution of rules, and offers a critique of later Buddhist traditions, particularly concerning meat consumption, and the alleged exaggeration in their scriptures. It also analyzes the final meal of Buddha, arguing it was likely a vegetarian dish rather than "pig's flesh."

Conclusion: "Manav Bhojya Mimansa" is a scholarly defense of vegetarianism rooted in Jain philosophy, Vedic heritage, and supported by scientific evidence. It aims to correct historical misinterpretations and guide readers towards a diet that is ethically sound, beneficial for health, and aligned with spiritual progress.