Mahavira Jivan Vistar

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Mahavira Jivan Vistar" (An Elaboration of Mahavira's Life) by Bhimjibhai Harjivandas, based on the provided pages:

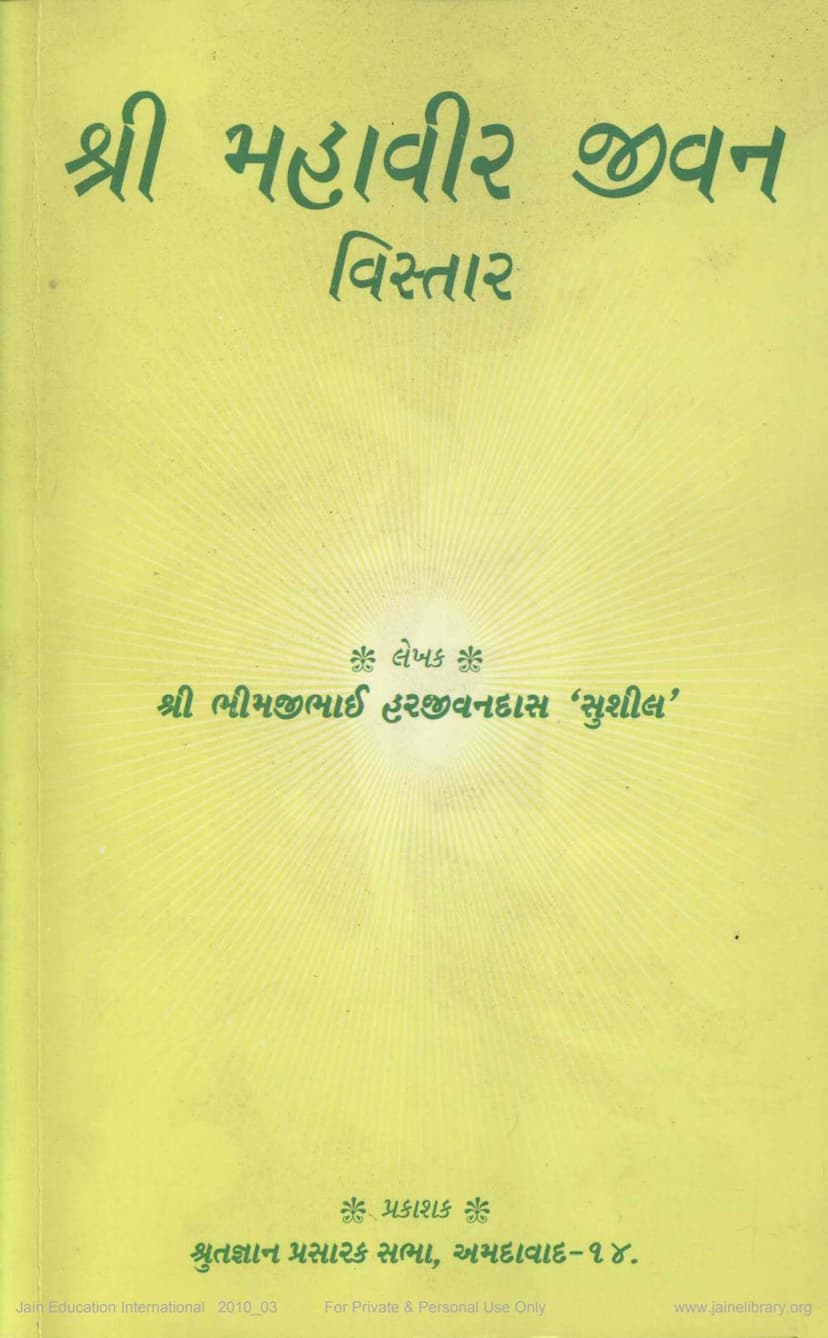

Book Title: Mahavira Jivan Vistar (An Elaboration of Mahavira's Life) Author: Bhimjibhai Harjivandas 'Sushil' Publisher: Shrutgyan Prasarak Sabha, Ahmedabad Publication Year: 2010 (2nd Edition mentioned as Vikrami Samvat 2065, implying the first edition was much earlier, around 1958 based on preface)

Overall Theme: "Mahavira Jivan Vistar" aims to provide a detailed and reflective account of the life of Lord Mahavir, the 24th Tirthankara of Jainism. The book delves into various aspects of his life, from his childhood and spiritual journey to his encounters with societal challenges and his profound teachings. It emphasizes the inner strength, detachment, and profound philosophy that guided his actions, often drawing parallels with the author's own insights and the context of the time.

Key Aspects and Chapters Summarized:

-

Introduction & Author's Background (Pages 1-7): The initial pages introduce the book and its author. Bhimjibhai Harjivandas 'Sushil' is described as a respected writer, journalist, and translator, known for his progressive views and contributions to Jain literature. He passed away at the age of 73. The publisher expresses the intent to re-publish his valuable works, recognizing their enduring relevance.

-

Publisher's Foreword (Page 9): The publisher emphasizes the inherent power within the soul and how Lord Mahavir's life exemplified this, demonstrating the potential for spiritual liberation. They state the book's purpose is to reiterate the teachings, similar to chanting a mantra for a specific benefit, and praise the author's skillful writing.

-

Introduction to the Second Edition (Pages 11-16): The author's colleague, Parmanand Kunvarji Kapadia, writes a preface. He notes the passage of 35 years since the book's first publication and acknowledges the evolution of thought. He highlights that the book presents a critical analysis of key events in Mahavir's life, from childhood to enlightenment, free from sectarian biases. He also mentions that the book includes an essay by Bhimjibhai on "Maha Deviyos" (Great Goddesses of Mahavir's era), specifically the stories of Devananda and Sunanda.

-

Foreword by Bhimjibhai Harjivandas (Pages 17-21): The author himself provides a foreword that is significant for its candidness and intellectual honesty. He addresses the potential for disagreement with his views within the Jain community, stating that he has presented his thoughts fearlessly and rationally. He acknowledges that if his interpretation clashes with established beliefs, readers should extend him kindness. He emphasizes that his writing is based on reasoned thought and not blind faith. He welcomes criticism that is constructive and polite, asserting his responsibility for the content and his willingness to accept the consequences of his writing.

-

Chapter 1: Childhood and Marriage (Pages 22-36):

- The author begins by quoting from the Acharanga Sutra about the non-discriminatory nature of birth and the futility of casteism.

- He offers salutations to Lord Mahavir, acknowledging the transformative impact of his teachings over 2484 years.

- The author addresses the divine interventions described in scriptures regarding Mahavir's birth (transfer from Devananda's womb to Trishala's by Indra). He acknowledges the difficulty of accepting such miraculous events in the scientific age but suggests that the underlying message is about the consequences of pride (like Mahavir's past life as Marichi) and the importance of humility.

- He details Mahavir's birth celebration, the descent of celestial beings, and the divine aura surrounding him. The name "Vardhamana" (increasing prosperity) is explained by the prosperity that followed his birth.

- Despite his divine nature, Mahavir's parents, Siddhartha and Trishala, arranged his marriage due to their parental affection. He married Yashoda, and they had a daughter named Priyadarshana.

- After his parents' death at 28, Vardhamana consoled his elder brother Nandivardhana and requested permission to renounce worldly life. Nandivardhana's plea to delay his departure is accepted, and Vardhamana spends an additional two years in domestic life, maintaining a detached yet exemplary life of austerity. The author highlights the exceptional nature of such conduct, contrasting it with ordinary individuals.

-

Chapter 2: Household Life and Acceptance of Asceticism (Pages 30-36): This chapter elaborates on Vardhamana's detached life within the household. His heart was detached from worldly pleasures, living like a lotus in water. He spent two years beyond the initial period requested by his brother, observing strict vows like celibacy, meditation, and minimal, pure food intake. His adherence to principles even in ordinary life is highlighted. Upon his departure for asceticism, he renounced his worldly possessions, family, and status without regret, symbolizing the ultimate detachment required for liberation.

-

Chapter 3: Tradition of Ordeals (Upasargas) (Pages 39-48):

- This chapter focuses on the intense hardships (upasargas) Mahavir faced during his 12 years of asceticism. The author emphasizes that these physical sufferings were not experienced with the same inner pain by Mahavir as they would be by an ordinary person, due to his advanced spiritual state and detachment (kshina mohaniya karma).

- He explains that great souls undergo suffering to exhaust their past karma and provide an example for others. The author notes that these hardships were not "unnecessary" but crucial for Mahavir's spiritual development and the karmic cleansing.

- He recounts specific incidents, like a cowherd’s cattle grazing near Mahavir, the cowherd's subsequent anger and search for his lost cattle, and Indra's intervention to explain Mahavir's divine nature. Mahavir's response to Indra's offer of help highlights his self-reliance and the principle that liberation is achieved through one's own efforts, not external aid.

- The author explains the nature of karma – some can be mitigated by spiritual practices, while "nikachita" (fated) karma must be endured. Mahavir's acceptance of suffering without regret is attributed to his understanding of this cosmic law.

- The chapter discusses the importance of empathy and mutual support, while also cautioning against interference that hinders an individual's karmic progression.

-

Chapter 4: The Glory of Silence (Mauna) (Pages 37-48):

- This chapter focuses on Mahavir's 12 years of silence following his initiation. The author posits that this period of silence was a deliberate choice to achieve his ultimate spiritual goal and provide a crucial lesson on self-improvement before becoming a spiritual guide.

- He critiques the tendency of some individuals to preach without having achieved their own spiritual perfection, comparing it to using a dirty cloth to clean another. The author stresses that true guidance comes from personal realization and exemplary conduct.

- He contrasts Mahavir's approach with the impulsive tendency of some modern preachers who share knowledge without deep personal experience, often leading to criticism and a lack of genuine impact. The author emphasizes the importance of mastering oneself before attempting to guide others.

-

Chapter 5: Ghoshala: The Ajivika Thinker (Pages 52-56):

- This chapter introduces Ghoshala, a contemporary spiritual leader and rival of Mahavir, who founded the Ajivika sect.

- The author defends Ghoshala against accounts in some Jain texts that portray him as foolish or deranged, suggesting that historical context and sectarian biases may have distorted his portrayal. He notes that Ghoshala was influential enough to be recognized by kings like Ashoka and that Ajivika philosophy, though now extinct, had significant tenets like compassion for all living beings.

- The author speculates that a philosophical disagreement, likely concerning determinism versus free will (Niyati vs. Purushartha), led to Ghoshala becoming an opponent of Mahavir.

-

Chapter 6: Initiation in Non-Aryan Territories (Pages 57-62):

- After 8 years of his ascetic life, Mahavir decided to move into "non-Aryan" (Anarya) regions, meaning areas less familiar with or less influenced by existing Aryan customs and teachings.

- The author suggests this was not to seek suffering but to avoid the potential pitfalls of excessive praise and comfort that he had received in his familiar surroundings. It was a deliberate choice to remain uninfluenced by external adulation and to provide an example of humility and detachment from honor.

- The chapter also touches upon the changing social landscape of the time, where the distinction between "Aryan" and "non-Aryan" was becoming less about lineage and more about conduct and civilization.

-

Chapter 7: Tejasleshya (Pages 63-68):

- This chapter describes an incident where Ghoshala, seeking to attain "Tejasleshya" (a fiery aura or power), confronted a tapas (ascetic) who was practicing intense austerities.

- Ghoshala's rude questioning led to the tapas generating intense heat (Tejasleshya), which threatened Ghoshala. Mahavir, observing this, generated "Sheetleshya" (cooling power) to protect Ghoshala.

- Ghoshala was amazed by this display of power and sought to learn the method from Mahavir. The author explains the concept of "Tapa" (austerity) as the control of desires and the channeling of willpower, which can manifest such powers.

- However, the author notes that Ghoshala, upon gaining this power, became arrogant and challenged Mahavir's spiritual authority, leading to his eventual divergence from Jain principles.

-

Chapter 8: The Severe Ordeal of Sangama (Pages 69-77):

- This chapter details a severe ordeal inflicted by a demon named Sangama (or according to some texts, a devata named Sangama). Sangama subjected Mahavir to immense physical suffering, including torturing him with poisonous insects and striking him with a heavy iron ball, causing him to sink into the ground.

- The author reiterates the principle of karma, stating that Mahavir endured this suffering because he had karmically caused a similar hardship to Sangama in a past life (as King Trisprastha who unjustly punished his attendant).

- The author also discusses the role of external forces like Indra, who, despite knowing Mahavir's advanced state, felt compassion and offered help, which Mahavir gently refused, emphasizing self-reliance.

- The chapter highlights Mahavir's unwavering equanimity and detachment, his ability to remain undisturbed by suffering, and his deep understanding of the karmic chain of cause and effect.

-

Chapter 9: Bhavana Bhavanasini (Contemplation that Destroys Existence) (Pages 78-88):

- This chapter uses the example of Jinadatta, a devoted but poor follower, and a wealthy merchant to illustrate the significance of "Bhavana" (contemplation/intention) over mere ritualistic action.

- Jinadatta yearned to offer Mahavir a meal, prepared with great devotion and austerity. However, Mahavir went to a wealthy merchant who offered him simple alms without genuine devotion.

- Jinadatta was distraught, but a wise monk explained that Jinadatta's pure intention and deep contemplation earned him a higher spiritual reward than the wealthy merchant's action, even though the latter offered better food.

- The author emphasizes that the quality of intention and inner state is paramount in spiritual practice, more so than outward actions or material offerings. He criticizes the superficiality of some modern religious practices that lack genuine devotion.

-

Chapter 10: Karna and Jo (Ear and Eye) (Pages 90-98):

- This chapter recounts two incidents illustrating Mahavir's unwavering composure and his understanding of karma.

- The Shepherd Incident: A shepherd asked Mahavir to watch his cattle. Mahavir, absorbed in meditation, didn't respond. The cattle strayed, and the shepherd, assuming Mahavir's complicity, tried to harm him. Mahavir's calm endurance, even when the shepherd tried to pierce his ear with a thorn, is highlighted. The author links this to Mahavir's past life as King Vasudeva, who unjustly punished his attendant by pouring molten lead into his ear. The current suffering was the karmic consequence.

- The Eye Ordeal: The text describes Mahavir enduring a painful ordeal related to his ear, possibly involving molten lead or a piercing. The author notes that this suffering was extreme, perhaps the most intense he faced, but Mahavir's detachment remained steadfast. The author reflects on the karmic implications of past actions and the nature of suffering, emphasizing that true understanding comes from detachment and non-attachment to the physical body.

-

Chapter 11: Devananda Mata (Mother Devananda) (Pages 105-110):

- This section focuses on Devananda, Mahavir's biological mother from a previous birth and the woman who carried him for the first 82 days before Indra transferred the embryo to Trishala.

- Devananda, a Brahmin woman, had auspicious dreams indicating the birth of a great soul. However, her joy was short-lived when the embryo was transferred.

- The author explains this transfer as a karmic consequence of Mahavir's past pride and Devananda's past act of stealing a jewel from Trishala.

- Despite the loss, Devananda is presented as a woman of acceptance and inner strength. Years later, Mahavir, during his public discourse, identifies himself to Devananda, reawakening her maternal feelings.

- Following this recognition, both Devananda and her husband, Rishabhdatta, embrace the Jain path and attain liberation.

-

Chapter 12: Sunanda (Pages 111-126):

- This is a narrative about Sunanda, a devoted disciple of Devananda and a young woman living in a Jain Ashram.

- Sunanda deeply revered Devananda, finding solace and guidance in her image. She struggled with worldly desires that arose, particularly after a vivid dream of family life.

- Unable to reconcile her aspirations with her monastic vows, Sunanda leaves the Ashram, seeking to fulfill her worldly desires. She encounters Jayant, a wealthy merchant, and they eventually marry and have children.

- Despite her worldly happiness, Sunanda remains spiritually inclined. Years later, she feels a call from Devananda and the Ashram. She leaves her family and worldly life, renouncing her possessions and returning to the Ashram, where she is accepted with compassion.

- The narrative emphasizes the enduring power of spiritual upbringing and the inherent spiritual nature of the soul, which can re-emerge despite periods of worldly indulgence. It highlights the conflict between worldly desires and spiritual aspirations and the ultimate triumph of devotion.

Conclusion: "Mahavira Jivan Vistar" provides a spiritual and philosophical exploration of Lord Mahavir's life. It emphasizes the importance of inner strength, detachment, the consequences of karma, and the ultimate path to liberation through self-effort and righteous conduct. The author's reflective style and willingness to engage with complex philosophical ideas make the book a valuable resource for understanding Mahavir's teachings and their relevance.