Mahavir Ka Buniyadi Chintan

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Mahavir ka Buniyadi Chintan" based on the provided pages:

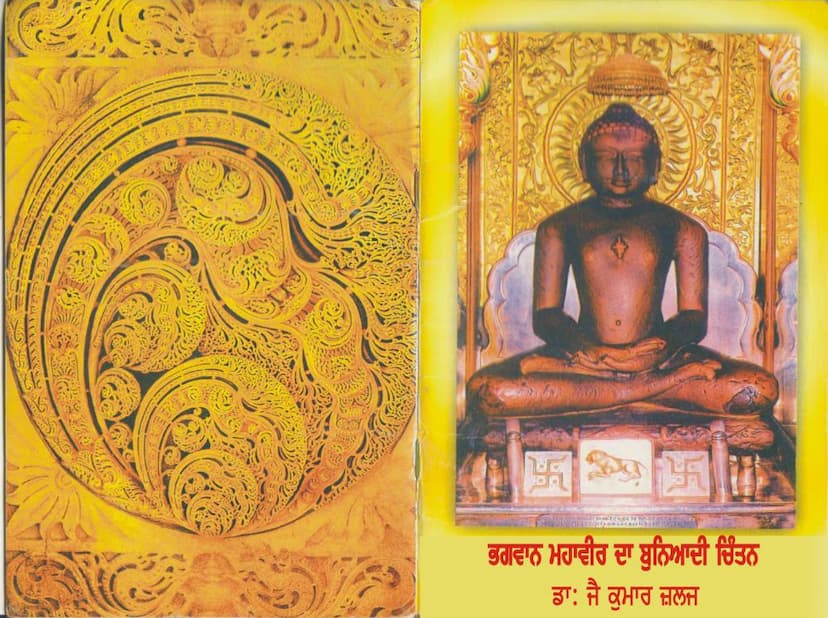

Book Title: Mahavir ka Buniyadi Chintan (The Fundamental Thought of Mahavir) Author: Dr. Jai Kumar Jalaj Translators: Ravinder Jain, Purushottam Jain (Malerkotla) Publisher: 26th Mahavir Janma Kalyanak Shatabdi Sahayojika Samiti Punjab

Overview:

This book, "Mahavir ka Buniyadi Chintan," aims to present the core philosophy and teachings of Lord Mahavir, the 24th Tirthankara of Jainism, in a concise and accessible manner. The Punjabi translation, by Ravinder and Purushottam Jain, highlights the book's importance and widespread recognition, having been translated into numerous Indian and foreign languages and going through multiple Hindi editions.

Key Themes and Concepts:

-

Mahavir's Life and Philosophy:

- Birth and Early Life: Born in 599 BCE in Vaishali, Kundgram, Mahavir belonged to a Kshatriya republic. His father was Raja Siddharth, and his mother was Trishala. His birth name was Vardhaman, and he was also known as Sanmati and Mahavir due to his intellect and valor.

- Republican Influence: Mahavir's upbringing in a republic instilled in him values of democracy, equality, freedom of speech, and transparency in decision-making processes. He observed these principles in the functioning of the Vajji confederacy, which included eight republics.

- Renunciation and Enlightenment: Mahavir's renunciation at the age of 30 was not an impulsive act but a result of deep contemplation. After 12 years of asceticism and meditation, he attained Kevala Jnana (omniscience) under a Shaal tree near the Rijukula river in 557 BCE.

- Fundamental Truth: Mahavir's core realization was the inherent greatness, independence, self-reliance, and multifaceted nature (Anekant) of all substances (Jiva and Ajiva). This understanding led him to advocate for respectful treatment of all beings and non-living entities.

-

The Concept of Substance (Vastu/Dravya):

- Multifaceted Nature: Mahavir emphasized that every substance has infinite qualities and aspects. This is the essence of Anekantavada (the doctrine of manifold aspects).

- Perspective and Relativity: What we perceive as true is often based on our limited perspective. Disagreements arise not from the substance itself but from the differing viewpoints of observers. Mahavir advocated for tolerance and leaving space for diverse perspectives.

- Change and Permanence: Substances are characterized by constant change (utpad, vyay) yet possess an enduring essence (dravya). The river, though always flowing and changing, remains a river. This unchanging essence is its inherent quality.

- Independence and Ownership: Substances are independent and not owned by anyone. The concept of ownership is a worldly convention.

-

Anekantavada and Syadvada:

- Anekantavada (Manifoldness): This is the fundamental principle that reality is composed of infinite aspects and perspectives.

- Syadvada (Conditional Predication): This is the linguistic expression of Anekantavada. The word "Syat" (perhaps/maybe) signifies that a statement is true from a particular perspective, while other perspectives may also hold truth. It acknowledges the limitations of language in fully capturing the totality of reality. Language is incapable of fully describing the vastness of substances; it can only present a partial, often imperfect, view.

-

Non-violence (Ahimsa) and Rights:

- Universal Rights: Mahavir's concern extended beyond human rights to the rights of all sentient and non-sentient beings. He considered environmental protection (water, forest, land) as crucial.

- Sentient and Non-sentient Beings: Mahavir classified beings into two types: Pranas (mobile, with one to five senses) and Sthavaras (immobile, with only one sense). The latter include earth, water, fire, air, and plants.

- Himsa in Non-essential Use: Causing suffering to Sthavara beings or their non-essential use is considered violence (Himsa) by Mahavir. Modern science is increasingly acknowledging the validity of Mahavir's perspective.

- The Essence of Himsa: True violence is rooted in internal passions like attachment (Raga), aversion (Dvesha), and delusion (Moha). Physical actions without these passions might not constitute severe violence. The intention and state of mind are paramount.

- Types of Himsa: The book discusses different types of violence: Arambhi (incidental, e.g., walking, bathing), Udyogi (occupational, e.g., farming, business), and Sankalpi (intentional, driven by greed, anger, ego, etc.). While the first two are difficult to avoid completely, Sankalpi Himsa is condemned as it stems from selfish desires and leads to spiritual downfall.

-

The Path to Liberation (Moksha):

- The Three Jewels (Triratna): Mahavir taught that the path to liberation lies in the attainment of Samyak Darshan (Right Faith/Perception), Samyak Jnana (Right Knowledge), and Samyak Charitra (Right Conduct). These three are interconnected and inseparable for achieving liberation.

- Samyak Darshan: This involves recognizing the true nature of the soul as distinct from the body and other substances, and having deep faith in the principles of Jainism.

- Samyak Jnana: This refers to accurate knowledge of the soul, reality, and the path to liberation.

- Samyak Charitra: This is the practice of righteous conduct, following the vows and ethical principles taught by Mahavir.

- The Role of Effort (Upadan and Nimitta): Mahavir emphasized that individuals are the primary cause (Upadan) of their own liberation. While external factors (Nimitta) can be supportive, they cannot replace individual effort. Trying to be the primary cause for others is a form of violence.

- Liberation from Karma: The soul is bound by karma. Liberation is achieved by stopping the influx of new karma (Samvara) and shedding existing karma (Nirjara) through spiritual practices and detachment.

- Detachment (Viraga): True liberation comes from detachment from worldly desires and passions, not just from actions. Even the desire for merit (Punya) can be an obstacle to ultimate liberation.

-

The Nature of the Soul (Atma/Jiva):

- Consciousness and Independence: The soul is the only conscious substance, inherently pure, infinite, and independent.

- Two Bodies: The soul is associated with two bodies: the gross physical body (Sthula Sharira) and the subtle karmic body (Sukshma Sharira or Karana Sharira), which is the repository of karma.

- Karma and Rebirth: The karmic body, formed by actions, determines the soul's journey through cycles of birth and death across various life forms.

- The Goal of Moksha: Liberation (Moksha) is the state of the soul becoming free from karmic bondage, realizing its true nature, and existing in a state of pure consciousness and bliss, detached from the physical body.

-

Mahavir's Teachings in Practice:

- Democracy and Equality: Mahavir's teachings reflect a deep understanding of democratic principles, evident in the inclusive nature of his spiritual assembly (Samosharan), which welcomed all beings.

- Language and Accessibility: Mahavir chose to preach in Prakrit, the common language of the people, making his teachings accessible to a wider audience.

- Beyond Ritualism: Mahavir opposed empty rituals, superstitions, and blind adherence to traditions. He advocated for rational thinking and self-effort.

- Compassion Rooted in Knowledge: Compassion (Daya) should stem from knowledge and understanding, not ignorance. Ignorant compassion does not lead to liberation.

- The Need for Balance: Mahavir's philosophy provides a balanced approach, advocating for individual responsibility while also recognizing the importance of supportive external factors. The concept of "Live and let live" (Jiyo aur Jine Do) encapsulates this principle.

- The Importance of Intention: The intent behind an action is crucial in determining its karmic consequence. Even unintentional harm can have karmic repercussions, but actions driven by malice have far greater negative impacts.

Conclusion:

"Mahavir ka Buniyadi Chintan" presents Mahavir's philosophy as a comprehensive and scientific system that addresses not only spiritual liberation but also ethical conduct, social harmony, and ecological consciousness. The book emphasizes the practical application of these principles in daily life, urging readers to strive for self-realization and a life of non-violence, truth, and detachment, thereby contributing to individual and collective well-being. The translators express hope that the Punjabi translation will effectively convey these profound teachings to a wider audience.