Mahatma Gandhi And Kavi Rajchandraji Question And Answered

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Mahatma Gandhi and Kavi Rajchandraji Questions Answered":

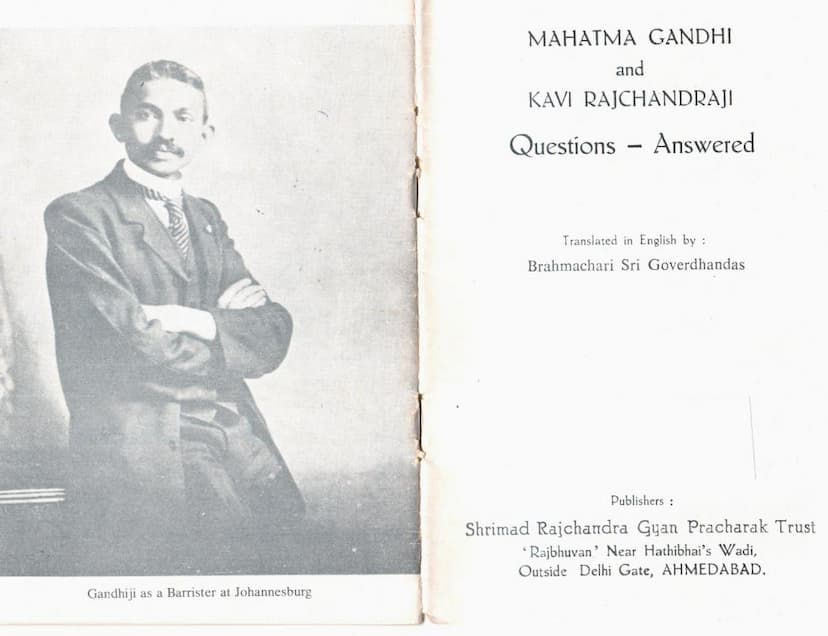

This book, translated by Brahmachari Sri Goverdhandas and published by Shrimad Rajchandra Gyan Pracharak Trust, presents a significant correspondence between Mahatma Gandhi and Kavi (Poet) Rajchandraji. Mahatma Gandhi himself acknowledged the profound influence of Rajchandraji on his life, particularly during periods of doubt about Hinduism. Their connection began in 1891 when Gandhi, upon returning from England, met Rajchandraji in Bombay. Gandhi was deeply impressed by Rajchandraji's wisdom and his remarkable ability as a "Shatavadhani" (one who can retain a hundred items in memory), despite Rajchandraji being only 25 years old, a student of vernacular classes, and without knowledge of English.

The core of the book consists of a series of questions posed by Mahatma Gandhi to Kavi Rajchandraji while Gandhi was in South Africa and experiencing a mental turmoil due to discussions with Christian missionaries. Gandhi sought clarity on various religious and philosophical matters, posing no less than 27 questions. The book reproduces a selection of these questions and Rajchandraji's detailed answers, highlighting the intellectual depth of both individuals.

Here's a breakdown of the key topics and answers discussed:

-

Soul and its Function: Rajchandraji explains the soul as a conscious substance, distinct from material substances. It is eternal and permanent, possessing inherent characteristics of knowledge, perception, and spiritual equanimity. In a state of ignorance, the soul can create negative emotions and, through its actions ("Karma"), can influence the material world, leading to the creation of objects. However, the soul itself is not the creator of these external things or emotions; rather, it is the creator of its own conscious characteristics. Karmas, performed in ignorance, have consequences that the soul must bear, leading to the cycle of birth, death, and suffering. Detachment and self-control are crucial for spiritual progress and Nirvana.

-

The Nature of God and Creation of the Universe: Rajchandraji defines Godhood not as an external creator but as the inherent state of the self when it is free from karmas, impurities, and bondages. God is characterized by fullness of peace, bliss, and knowledge. God is synonymous with the self; there is no abode of God outside the self. The universe and its elements are eternal and uncreated. God is not the creator of the universe, as it is impossible for the sentient (God) to create the insentient (atoms, space) or vice versa. The universe consists of both sentient (Jivas) and insentient elements. God is also not the giver of the fruits of actions.

-

Nature and Possibility of Moksa (Salvation): Moksa is defined as the absolute liberation of the self from negative propensities like anger, conceit, greed, and ignorance that bind the soul. This liberation is possible for an embodied soul. As the soul gradually sheds these binding emotions, it experiences a growing sense of freedom and the glory of salvation, even while residing in a physical body.

-

Transmigration in Lower Conditions of Life: When a soul leaves one body for another, it moves according to its accumulated karmas. This can involve taking on animal, mineral, or vegetable forms. In the mineral state, the soul experiences the fruits of its karmas through the sense of touch alone, appearing in a physical form akin to stone but remaining distinct from it. The soul's embodiment in a particular form is like wearing an apparel, not its inherent nature. The soul, not the physical form, is the doer of karmas.

-

The Nature of Dharma (Religion): "Arya Dharma" or sublime religion is defined as the spiritual path that leads to self-realization, a path claimed by various faiths. Rajchandraji expresses doubt that "almost all" religions originated from the Vedas, arguing that the knowledge of the Tirthankaras and other great teachers surpasses that of the Vedas. He asserts that while antiquity doesn't equate to truth, the eternal nature of principles from various faiths needs to be assessed for their strength and effectiveness in achieving life's aspirations.

-

The Vedas and the Bhagwad-Gita: Rajchandraji suggests the Vedas are old compositions and that scriptures, by their teachings, are eternal as their principles have been expressed in various ways throughout time. However, the physical form of a book is not eternal. Regarding the Bhagwad-Gita, he believes Veda Vyasa composed it and that the teachings originate from Lord Krishna. While acknowledging the teachings' eternal nature, he questions the concept of an inactive God composing a book, suggesting an active, embodied being as the composer. He considers scriptures containing divine teachings as "God's Book."

-

Bloody Sacrifice and Rationalism: Rajchandraji condemns bloody sacrifice, stating that causing pain or slaughtering animals results only in demerit. Associated alms-giving with himsa (violence) is also discouraged. He emphasizes the importance of reason in understanding Dharma, stating that teachings must be supported by valid reasons and should prove effective in destroying the cycle of births and deaths and leading to a state of purity and peace.

-

Christianity, Bible, and Jesus Christ: While possessing ordinary information about Christianity, Rajchandraji notes that Indian sages' methods of thought and achievement differ from those in Christianity. He finds Christianity less appealing due to its limited focus on the intrinsic nature of the soul and the causes and remedies for life's vicissitudes. He questions the belief that the Bible is the word of God and Jesus Christ is His son, as such claims cannot be proven and contradict the nature of a liberated God who is devoid of attachment and aversion. He believes Jesus can be allegorically considered a son of God but not rationally. He also questions the concept of miracles in the Bible, suggesting that while spiritual discipline can lead to powers, resurrection as described is impossible.

-

Prophecy and Miracles: Prophecies, even if they come true, are not sufficient proof of a divine incarnation, as they can be based on astrology or intuition. Similarly, miraculous powers might be attained through spiritual discipline but are inferior to the soul's omnipotent glory.

-

Past and Future Incarnations: Rajchandraji affirms that it is possible to know about past and future births through intuition and logical reasoning by observing the tendencies of a being.

-

Omniscient Teachers: The proof of omniscient teachers lies in their ability to inspire peace, bliss, and excellence in others, indicating their attainment of Moksa. Scriptures also corroborate this truth.

-

The Conditions of the Universe and Pralaya: Rajchandraji believes the universe is a continuous process of change, birth, death, integration, and disintegration. He considers the idea of total destruction or "Pralaya" of the universe to be impossible, as nothing is absolutely destructible. He also finds the concept of all souls merging into one without distinction to be untenable, as it would lead to a complete cessation of activity, and the subsequent restart of activity would be inconceivable.

-

Bhakti (Devotion) and Moksa: Bhakti leads to knowledge, which in turn leads to Moksa. While literacy is helpful, it is not compulsory for acquiring self-knowledge. Perfect knowledge is essential for Moksa.

-

Avatars (Krishna and Rama): Rajchandraji views Rama and Krishna as great personages who were souls and, if they achieved Moksa, were also God. He rejects the theory of a living being being a "part of God" as it undermines the distinction between bondage and liberation and would attribute nescient tendencies to God. He suggests they were "God in embryo" but questions whether the full glory of Godhood bloomed in them. Worshipping them can be fruitful if their teachings lead to the spiritual state of freedom from attachment, aversion, and ignorance.

-

Brahma, Vishnu, and Mahesh'a: Rajchandraji suggests these terms might represent fundamental functions of the universe (creation, maintenance, disruption) or allegorical aspects of a primeval Lord. He finds the Puranic accounts less appealing and prefers an allegorical interpretation that derives lessons without getting into controversial details.

-

The Problem of Ahimsa (Non-violence): When confronted with a dangerous situation like a snakebite, those focused on spiritual good should offer their body rather than kill the creature. For others, Rajchandraji advises against killing the snake, viewing it as a non-Aryan attitude. He encourages aspiring for freedom from such an attitude.

The book concludes with Rajchandraji's advice to Gandhi to study "Shatdarshan Samuchchaya" and ponder the answers seriously. He also suggests that meeting in person would be the best way to discuss these profound questions further. The text emphasizes the profound intellectual and spiritual dialogue between these two great figures of the 20th century.