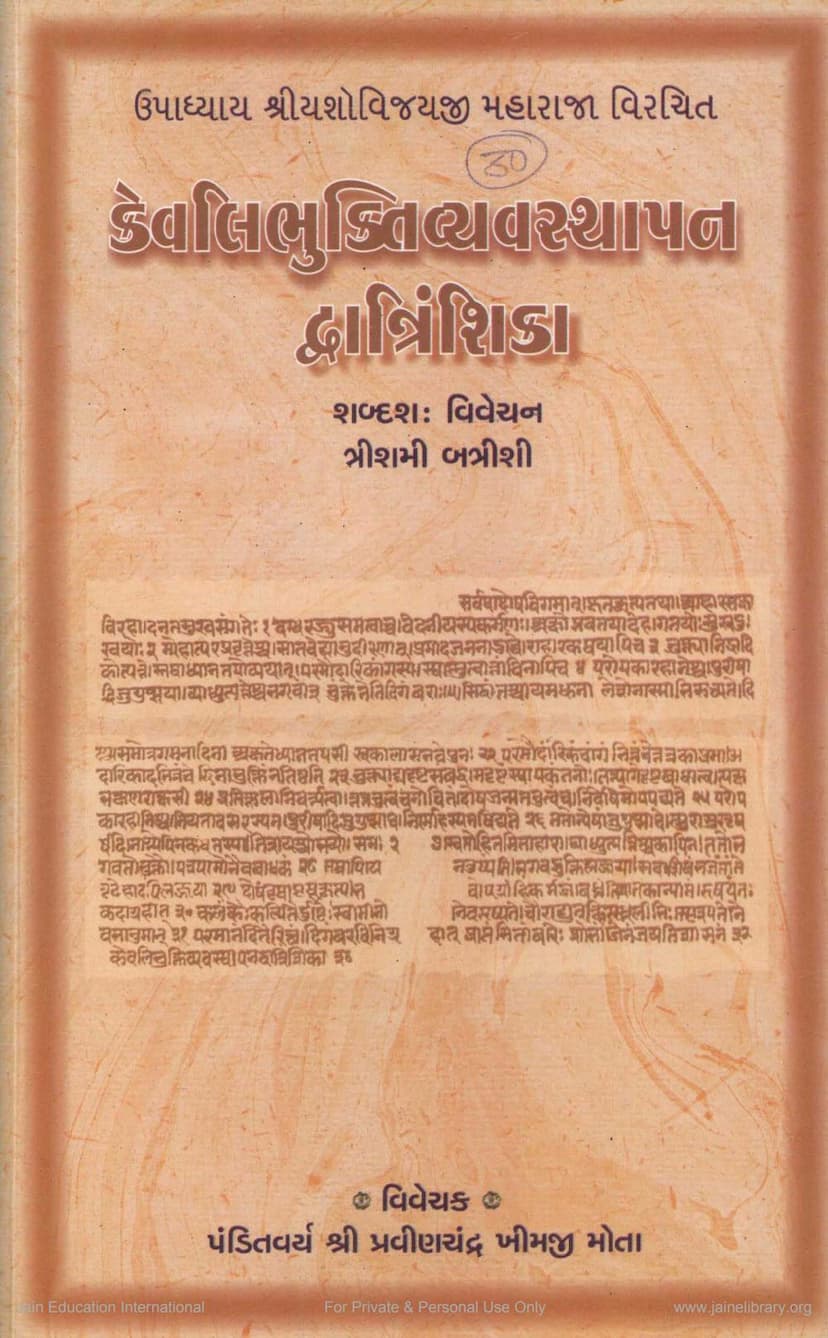

Kevalibhukti Vyavasthapana Dvantrinshika

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Kevalibhukti Vyavasthapana Dvātrinśikā" by Upadhyay Shri Yashovijayji, based on the provided pages:

Title: Kevalibhukti Vyavasthapana Dvātrinśikā (Meaning: Establishing the Practice of Food for the Omniscient)

Author: Upadhyay Shri Yashovijayji Maharaj (a prominent Jain scholar of the 17th-18th century)

Commentator: Panditvar Shri Pravinchandra Khimji Mota

Publisher: Gitarth Ganga

Core Subject:

This text is the 29th chapter (Dvātrinśikā) within a larger work by Upadhyay Yashovijayji titled "Dvātrinśad Dvātrinśikā" (Thirty-two Chapters of Thirty-two Verses). The specific chapter, "Kevalibhukti Vyavasthapana Dvātrinśikā," addresses a significant theological debate within Jainism concerning whether an Kevali (an omniscient being who has attained liberation) partakes in food (Kevalibhukti or Kavalāhāra).

Central Argument and Context:

The text focuses on refuting the Digambara sect's assertion that Kevalis do not consume food. The Digambara viewpoint is that Kevalis are entirely free from all defects, have achieved all their goals (Kṛtakṛtya), have no desire for sustenance (Āhārasañjñāviraha), and possess infinite bliss, all of which, they argue, preclude the possibility of eating. They believe that partaking in food would be a defect or a sign of incomplete achievement.

Upadhyay Yashovijayji, representing the Shvetambara tradition, argues for the contrary, asserting that Kevalis do consume food. He counters the Digambara arguments by:

- Deconstructing "Defect-Free": While Kevalis are free from ghati (obscuring) karmas, they still possess aghati (non-obscuring) karmas, such as Vedaniya (feeling). The experience of hunger (Kṣudhā), arising from Vedaniya karma, is not considered a defect in the same way as the passions like anger or ignorance arising from ghati karmas.

- Reinterpreting "Kṛtakṛtya": Even though Kevalis have achieved their ultimate goal of liberation, they still possess the physical body (audārika śarīra) due to the remaining aghati karmas. The maintenance of this body, even for the purpose of the body's natural functions or the benefit of others (like teaching), is not seen as diminishing their achieved state.

- Challenging the "No Desire" Argument: While Kevalis are free from the desire driven by passions (moha), the natural functioning of the body due to remaining karmas, such as the need for sustenance, is not considered a "desire" in the same negative sense.

- Addressing the "Infinite Bliss" Argument: The infinite bliss of a Kevali is not negated by the physical sensation of hunger or the act of eating, as these are related to the remaining physical existence, not to the state of liberation itself.

- Analyzing the Role of Karmas: The text meticulously analyzes the nature of Vedaniya karma (feeling), specifically the experience of hunger. It argues that while the cause of hunger is Vedaniya karma, the experience of it does not diminish the Kevali's omniscience or liberation.

- Using Analogies: The text employs analogies, such as a burnt rope (dagdharajjū) to explain the nature of remaining aghati karmas, and the interaction of senses with objects, to illustrate its points.

- Critiquing Digambara Logic: Yashovijayji systematically dismantles the Digambara reasoning, pointing out logical fallacies and misinterpretations of Jain scriptures. He highlights that if minor bodily functions or sensations are considered disqualifying for a Kevali, then even their mere existence in a physical form (human body) would be a defect.

- Emphasis on Shvetambara Tradition: The text implicitly and explicitly supports the Shvetambara view that Kevalis consume food, which is described as a reflection of the glory and purity of the Jain tradition.

- Philosophical Depth: The text engages with profound philosophical concepts like the nature of karma, the distinction between ghati and aghati karmas, the state of liberation, and the nuances of perception and knowledge.

- Debate with Other Schools: While primarily addressing the Digambara viewpoint, the text also engages with general philosophical arguments relevant to ascetic practices and spiritual attainment, drawing upon principles found in various Indian philosophical schools.

Key Arguments Refuted (Digambara Claims and Yashovijayji's Rebuttals):

- Digambara Claim: Kevalis are free from defects (like hunger).

- Yashovijayji's Rebuttal: Freedom from ghati karmas doesn't mean freedom from all physical sensations arising from aghati karmas like Vedaniya. Hunger is a sensation from Vedaniya karma.

- Digambara Claim: Kevalis are "Kṛtakṛtya" (accomplished all goals).

- Yashovijayji's Rebuttal: Kṛtakṛtya applies to the ultimate goal of liberation from all karmas. The body, maintained by aghati karmas, still has natural functions.

- Digambara Claim: Kevalis have no desire for food (Āhārasañjñāviraha).

- Yashovijayji's Rebuttal: They are free from desire driven by passion (moha), not from the body's natural needs. The mention of aghati karmas like Vedaniya implies the possibility of sensation, not necessarily passionate desire.

- Digambara Claim: Eating would violate their infinite bliss.

- Yashovijayji's Rebuttal: Physical sensations are distinct from the pure, unalloyed bliss of the soul, which is not affected by bodily needs.

- Digambara Claim: Food leads to sleep, indigestion, etc. (defects).

- Yashovijayji's Rebuttal: The text argues that these are not inherent to food but depend on how it's consumed and the state of the body. Kevalis, by their perfect knowledge, would avoid any negative consequences. The text also counters specific claims about food leading to sleep, improper knowledge (rasanmatijñāna), or violation of īryāpatha (path of movement).

- Digambara Claim: Food expenditure (bhukti) would waste their meditation and austerity.

- Yashovijayji's Rebuttal: Their meditation and austerity are in their very nature and state of being, unaffected by the bodily need for sustenance.

- Digambara Claim: Kevalis are free from shame regarding bodily waste.

- Yashovijayji's Rebuttal: The text argues that if purity is the standard, then even the existence of a human body would be shameful, and if nakedness is not shameful due to divine attributes, then bodily waste from a Kevali, especially if unseen or naturally occurring, shouldn't be either.

- Digambara Claim: Food causes disease.

- Yashovijayji's Rebuttal: Kevalis eat only what is beneficial and in moderation, naturally free from disease.

Significance:

This text is a vital contribution to Jain theological discourse, offering a rigorous, logical, and scripturally supported defense of the Shvetambara position on the nature of the Kevali state. It showcases the intellectual prowess of Upadhyay Yashovijayji in resolving complex doctrinal disputes through detailed argumentation. The commentary by Pandit Pravinchandra Mota makes these intricate arguments accessible to modern readers.