Karmgranth Vivechan

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

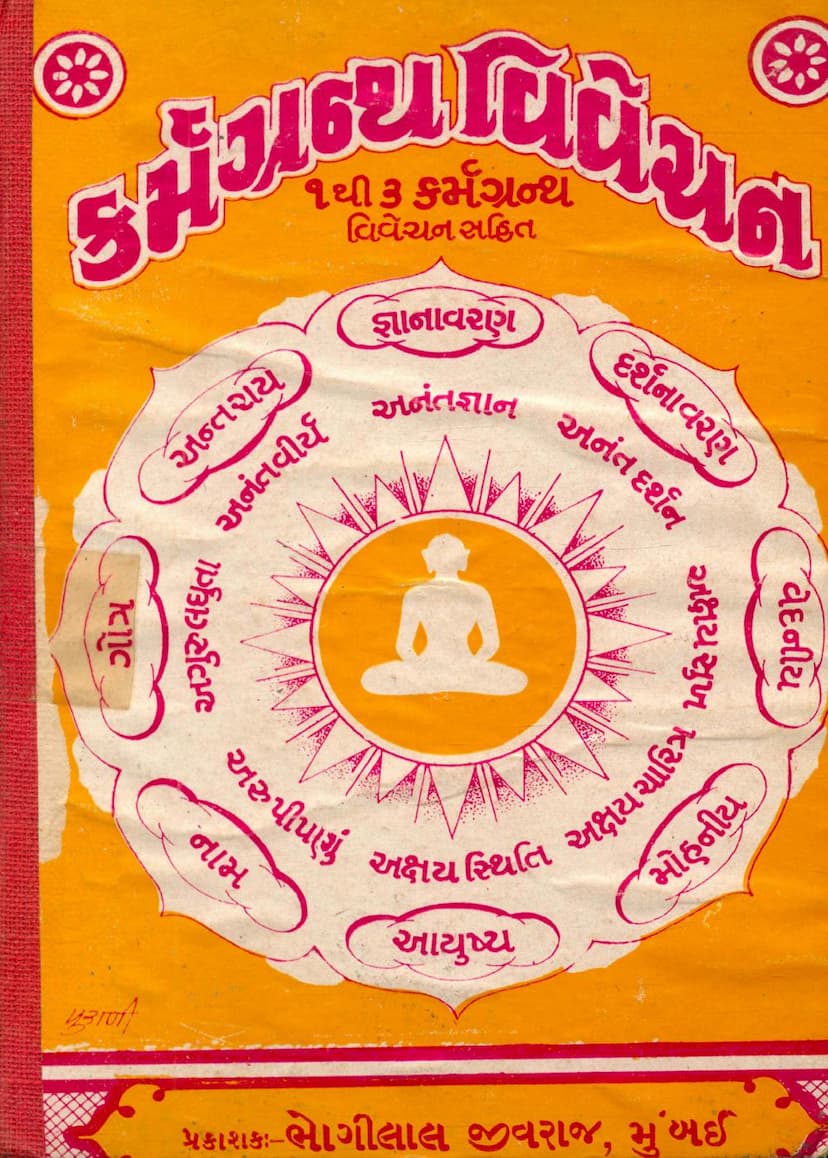

The book "Karmgranth Vivechan" (Vol. 1-3) by Acharya Shri Devendrasuri, with commentary by Pandit Bhagwandas Harkhchand, is a comprehensive Jain text that delves deeply into the concept of karma. Published by Bhogilal Jivraj in Mumbai, this work aims to provide a thorough understanding of karmic principles within Jain philosophy.

Here's a breakdown of the key themes and content covered in the provided pages:

Core Jain Philosophy and Karma:

- Karma as a Cause: The book emphasizes that karma is a primary cause for the various states of happiness and suffering, knowledge and ignorance, gain and loss, victory and defeat, prosperity and adversity experienced in life.

- Rejection of an External Creator God: Unlike other philosophies that attribute the creation and functioning of the universe to God, Jainism posits that the world is eternal and self-regulating. Jainism does not believe in an Ishvara (God) as the creator or controller of the universe. The universe is considered to be in a state of constant transformation and does not require divine intervention for its existence or evolution.

- Karma and Free Will: Jainism stresses that individuals are responsible for their actions. Just as a living being is free to perform actions (karma), they are also independently responsible for experiencing the consequences of those actions. Jainism does not rely on an external divine entity to dispense karmic fruits.

- Addressing Counter-Arguments: The text systematically addresses common arguments made by those who believe in an Ishvara (God) as the creator and dispenser of karma. These include:

- The argument from creation: Just as man-made objects require a creator, the universe, being a grand creation, must also have a creator.

- The argument from morality and justice: Since no one desires bad results from their actions, there must be a divine power that guides karma to dispense just rewards.

- The argument from divine attributes: Ishvara, being eternally free and possessing superior qualities, cannot be equated with liberated souls, and thus the idea that all souls can become Ishvara-like upon liberation is questioned.

Rebuttals and Jain Perspectives:

- Eternal Universe: The Jain view is that the universe is eternal and infinite, not created at any point. It undergoes transformations, some of which do not require the intervention of a creator.

- Inherent Power of Karma: While karma is considered inert, it gains a unique power through its association with consciousness (the soul). This inherent power, when activated by the soul's intentions (adhyavasaya), leads to the manifestation of results at the appropriate time. Karma does not require external divine inspiration to yield its fruits.

- Soul's Purity and Liberation: The difference between an ordinary soul and God lies in the coverings of karma that veil the soul's innate powers. When a soul sheds these karmic coverings through righteous conduct and effort, its inherent powers are fully revealed, making it equivalent to God. The difference is considered an "upadhik" (accidental) state caused by karma. Once karma is eradicated, the soul becomes Ishvara-like. All souls are inherently divine, but their manifestation in various forms is due to karmic bondage.

Utility and Importance of Karma Theory:

- Psychological Consolation and Understanding: The karma theory provides immense solace and understanding when individuals face adversities. Instead of blaming external factors or others, a thoughtful person realizes that their current suffering stems from their own past actions, sown like seeds and nurtured by favorable inclinations. This self-reflection leads to the elimination of enmity towards others and fosters inner strength.

- Personal Responsibility and Self-Purification: The doctrine of karma promotes self-introspection, personal accountability, and the pursuit of self-purification.

- External Recognition: The text cites Dr. Max Müller's thoughts on the impact of the karma theory, highlighting its effectiveness in reducing human suffering, fostering resilience in the face of adversity, and encouraging ethical living for a better future. Dr. Müller praises the karma theory as the most widely accepted ethical doctrine that has alleviated human suffering and encouraged individuals to bear present difficulties and improve their future lives.

Historical and Traditional Context of Karma in Jainism:

- Traditional View: Jainism and the concept of karma are considered inseparable and beginningless. The flow of karma is an intrinsic part of the Jain religious tradition.

- Historical View: The foundational figures of Jainism, Lord Parshvanath and Lord Mahavir, are considered the originators of the karma doctrine. Modern historians trace the history of Jainism to Lord Parshvanath, suggesting the karma principle is as ancient as his teachings. The principles of Lord Parshvanath and Lord Mahavir on karma were essentially the same, with only minor variations in rituals and practices based on time and place.

- Comparison with Other Religions: The text contrasts Jainism's karma theory with that of Vedic and Buddhist traditions. While Vedic and related philosophies acknowledge karma, they often involve God's role in dispensing karmic results. Buddhism accepts karma but includes the concept of "momentariness," which Jainism argues is incompatible with the idea of personal karmic responsibility and the continuity of the soul.

Evolution and Structure of Jain Karma Literature:

- Three Divisions: Jain karma literature is categorized into three main divisions:

- Purvatmak Karma Shastra: The oldest layer, found in the Fourteen Purvas, with specific sections dedicated to karma. Though its original form is lost, its essence is believed to be preserved in later texts.

- Uddhritakashastra from Purvas: Texts derived from the Purvas, smaller in scale but substantial for modern students. Both Śvetāmbara and Digambara traditions have such texts.

- Prakaranik Shastra: Contemporary works comprising various chapters and treatises on karma, which are currently the most widely studied and form the basis for understanding the earlier texts. These were compiled between the 8th and 16th centuries CE.

- Languages of Karma Literature:

- Prakrit: The language of the earliest Purvatmak and Uddhritak texts, including ancient commentaries (chūrṇis).

- Sanskrit: Used for later commentaries, explanations, and some original Prakaranik texts.

- Regional Languages: Gujarati, Kannada, and Hindi were used for translations and original works, with Gujarati being prominent in Śvetāmbara literature and Kannada and Hindi in Digambara literature.

Purpose of Karma Shastra:

- Spiritual Goal: Karma Shastra is an integral part of Adhyatma Shastra (Spiritual Science), aiming to impart true knowledge of the soul's ultimate (paramārthik) and phenomenal (vaibhāvik) nature.

- Understanding the Phenomenal State: It primarily focuses on the soul's phenomenal state, which is conditioned by karma. By understanding the current karmic states and their causes, one can then work towards eliminating them to achieve the ultimate spiritual state.

- Distinguishing Soul from Matter: Karma Shastra delineates the soul's true nature from its karmic impurities, highlighting the soul's inherent purity and its distinctness from physical (pogalik) karma. This understanding is crucial for attaining self-realization.

Detailed Explanation of Karmic Concepts:

- Dravya Karma and Bhava Karma: The text explains the two fundamental types of karma:

- Dravya Karma: Physical karmic particles (pudgals) attracted by the soul's passions.

- Bhava Karma: The soul's internal states of passion (rāga-dvesha, etc.) that lead to the attraction of dravya karma. These are mutually causative and have been occurring since beginningless time.

- Eight Types of Karma: The book systematically details the eight primary types of karma (mūla prakruti) and their numerous subdivisions (uttar prakruti):

- Ghāti (Obscuring) Karmas: Jñānāvaraṇīya (knowledge-obscuring), Darśanāvaraṇīya (perception-obscuring), Mohaniya (delusion-causing), and Antarāya (obstacle-creating). These directly veil the soul's essential qualities.

- Aghāti (Non-Obscuring) Karmas: Vedanīya (feeling-producing), Nāma (name/body-forming), Gotra (status-determining), and Āyuṣya (lifespan-determining). These do not obscure the soul's intrinsic nature but influence external circumstances.

- Bondage and its Causes: The text explains how karma binds to the soul through causes like Mithyātva (false belief), Avirati (non-restraint), Kashāya (passions), and Yoga (activity of mind, speech, and body).

- Stages of Karmic Manifestation: It elaborates on the four stages of karma: Bandha (bondage), Udaya (fruition), Udīraṇā (premature fruition), and Sattā (co-existence).

- The Eight Karmas and their Subdivisions: The book provides detailed explanations of each of the eight karmas, including their nature, the types of sub-categories (uttar prakruti), and the specific causes leading to their bondage. For example, it details the eight types of Mohaniya karma (four kashāyas, three vedas, and six no-kashāyas) and their respective impacts.

Specific Examples and Analogies:

- Modak Analogy: The text uses the analogy of a sweet dish (modak) to explain the four types of bondage: Prakruti Bandha (nature of the ingredients), Sthiti Bandha (how long it remains edible), Rasa Bandha (taste), and Pradesha Bandha (amount of ingredients).

- Analogy of Eye Covering: Jñānāvaraṇīya karma is likened to an eye covering, and Darśanāvaraṇīya karma to a curtain, illustrating how they obscure the soul's perception and knowledge.

- Analogy of Poisoned Food: The impact of karma is compared to consuming poisoned food; even if one doesn't desire the result, the effect is inevitable.

The Role of Intention and Character:

- Intention is Key: The text emphasizes that the intention behind an action, particularly the purity or impurity of the mind (bhava karma), is crucial in determining the karmic outcome.

- Strength of Character: It highlights that strong-willed individuals can overcome the influence of unfavorable circumstances (hetu) by maintaining equanimity and not succumbing to negative mental states, thereby preventing new karmic bondage.

The Book's Structure and Content (based on the Index):

The detailed index (vishayanukram) reveals the comprehensive nature of the content. It covers:

- Karmavipak Vivechan: Detailed explanation of karmic principles, types of karma (dravya and bhava), reasons for believing in karma, and solutions to philosophical queries.

- Types of Bondage: Prakriti Bandha, Sthiti Bandha, Rasa Bandha, and Pradesha Bandha.

- Eight Karmas and their Subdivisions: Detailed descriptions of Jñānāvaraṇīya, Darśanāvaraṇīya, Vedanīya, Mohaniya, Āyuṣya, Nāma, Gotra, and Antarāya karmas, including their numerous subdivisions.

- Types of Knowledge (Jñāna) and Perception (Darśana): Explanations of Matijñāna, Śrutajñāna, Avadhijñāna, Manahparyāvjñāna, and Kevaljñāna, along with their respective Darśanas.

- Kashāyas and No-Kashāyas: Detailed discussion of the four primary passions (kashāyas) and their subdivisions, as well as the nine no-kashāyas.

- Lifespan Karma (Āyuṣya Karma): Explanation of the four types of lifespan karma.

- Name Karma (Nāma Karma): Extensive breakdown of the 103 subdivisions of Nāma Karma, including categories like gati, jāti, śarīra, etc.

- Gotra Karma: Explanation of the two types of Gotra Karma.

- Antarāya Karma: Details on the five types of obstacle-creating karma.

- Causes of Karma Bondage: Specific factors leading to the bondage of each karma type.

- Special Treatises (Parishishta): Appendices discussing various aspects of karma, including the interpretation of karmic classifications in Digambara literature and comparative analysis of different schools of thought.

- Karmastav and Bandhasvāmitva: These sections delve into specific hymns and the owner (svāmī) of bondage in different karmic states and soul stages (guṇasthāna).

- Guṇasthāna Analysis: A significant portion is dedicated to explaining the fourteen guṇasthānas (stages of spiritual development) and how different karmas are bound, undergo fruition, mature, or remain in potentiality at each stage.

In essence, "Karmgranth Vivechan" is a profound and systematic exploration of the Jain theory of karma, providing a detailed framework for understanding the mechanics of karmic influence on the soul's journey and offering guidance for spiritual liberation.