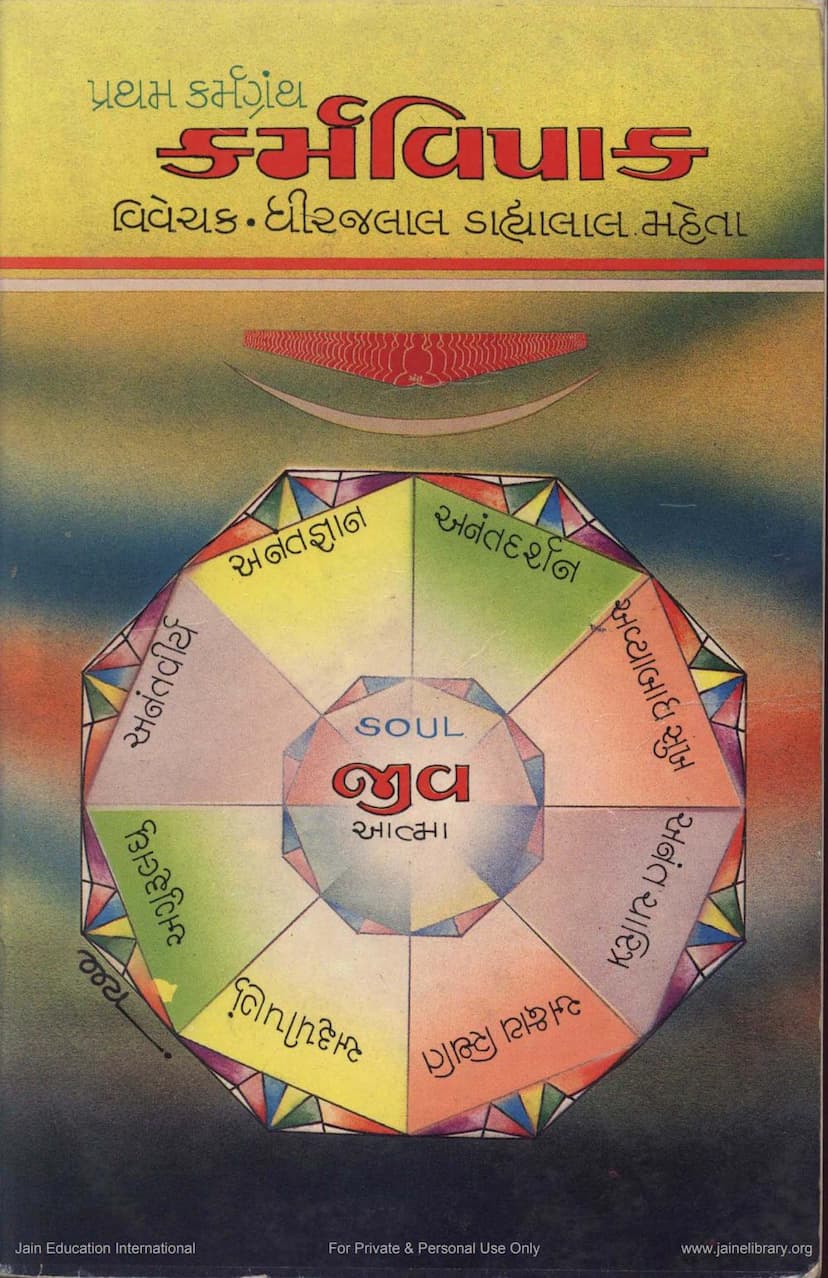

Karmagrantha Part 1 Karmavipak

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

This Jain text, "Karmagrantha Part 1 Karmavipak," authored by Devendrasuri and elucidated by Dhirajlal Dahyala Mehta, published by Jain Dharm Prasaran Trust, Surat, is a comprehensive exploration of the Jain concept of Karma. The catalog link provided is https://jainqq.org/explore/001086/1.

The book, as per the provided text, is written in Gujarati and aims to explain the intricate principles of Karma in a simplified manner. It includes the original verses (Gathas), Sanskrit translation, word-by-word meaning, verse-wise meaning, useful commentary, and a glossary of technical terms. It also features an appendix by Muni Shri Abhayshekhar Vijayji.

Here's a summary of the key concepts discussed in the initial pages and the introduction to the text:

1. The Nature of Karma:

- The text begins by stating that Karma is an unseen force, the primary cause for the varied conditions of beings in the world – be it happiness or suffering, health or illness, royalty or poverty.

- When external causes for these states are not apparent, humans often attribute them to Karma, Fate, or Destiny.

- The Soul (Atma) is described as a conscious substance, inherently pure, intelligent, immaculate, like a crystal, and independent.

- The Soul has two states:

- Impure State (Ashuddhavastha): When entangled with Karma.

- Pure State (Shuddhavastha): When devoid of Karma.

- All beings in the eternal cycle of existence (Samsara) are in an impure state, meaning the Soul and Karma have been associated since time immemorial.

- Karma itself is defined as a physical substance (Pudgal Dravya), external to the Soul, inanimate, and possessing attributes like color, smell, taste, and touch. However, it is extremely subtle and imperceptible to the eyes.

- The analogy of dust clinging to a wet or oily body is used to explain how subtle karmic particles (Karma Vargasnas) from the Lokakash (cosmic space) attach to the Soul when it becomes tainted by actions (Yoga) and passions (Kashaya).

2. The Soul's Agency and Responsibility:

- When the Soul is in a pure, Karma-free state (like the Soul in Moksha), it neither binds nor experiences Karma. It is an non-doer and non-experiencer.

- However, when the Soul is in an impure, Karma-laden state, it becomes the doer and experiencer of Karma. The body and senses are merely instruments.

- The text clarifies that those who claim the Soul is merely a knower-seer and not a doer/experiencer are only describing the state of Vitaraga (passionless) or liberated beings. For beings in Samsara, this claim is rooted in ignorance, as they are indeed doers and experiencers of Karma due to their impurity.

3. The Importance of Understanding Both States:

- From a spiritual perspective (Adhyatmik Drishti), it's crucial to understand the Soul's pure state to achieve it, and equally important to understand the impure state to avoid it and escape it.

- Just as one needs to know desirable qualities for engagement, one also needs to know undesirable qualities for renunciation.

- The text emphasizes the necessity of knowing Karma and its constituents thoroughly, just as one needs to know the qualities of gems while purchasing them, and also be aware of their flaws or artificiality.

4. Karma in Different Indian Philosophical Systems:

- The introduction highlights that various Indian philosophical systems (except Charvaka) accept the concept of Karma, albeit with different terminology.

- Systems that believe in rebirth (Punarvabhava) and past lives (Purva Bhava) inherently accept Karma.

- Nyaya-Vaisheshika, which believe in an Ishvara (God) as the creator, also accept Karma by positing Dharma (merit) and Adharma (demerit) as qualities that determine one's destiny. When questioned about an all-merciful God creating diverse experiences, they attribute it to the good and bad Karma of beings.

- Samkhya philosophy posits Purusha and Prakriti, with Prakriti being the source of worldly manifestations. The Soul (Atma) experiences actions and consequences through association with Prakriti, which is equated to Karma.

- Buddhist philosophy identifies mental, verbal, and physical consciousness as Karma, the cause of Samsara, and categorizes it into four types: Janaka, Upastambhak, Upapidak, and Upaghatak.

- Mimamsa philosophy accepts Karma through the concept of Avidya (ignorance of reality), which leads to Karma bondage. The power of Karma is called 'Apurva'.

- The text notes that while other philosophies acknowledge Karma, Jainism possesses an exceptionally vast and subtly analyzed literature on Karma, including its transformations like Udvarta and Apavartana, which are not found elsewhere.

5. The Jain Tradition and Karmagranthas:

- The text emphasizes that Jainism has a rich tradition of literature on Karma, created by numerous scholars from Ganadhar Bhagwantos to the present day, in Sanskrit, Prakrit, Gujarati, and Hindi.

- Lord Mahavir Swami's enlightenment ignited the lamp of Shrut Gyan (scriptural knowledge), which has been sustained by scholars through their scriptural creations.

- The introduction then outlines the major Jain traditions: Shvetambar and Digambar, both of which have produced significant works on Karma.

- It then lists various historical Karmagranthas, differentiating between "Ancient Karmagranthas" and "Modern Karmagranthas."

- Ancient Karmagranthas: Mentioned are "Karmavipak" (by Garg Rushimuni), "Karma Stav," "Bandh Swamitva," "Shadashiti" (by Jinvallabh Gani), "Shatak" (by Shivsharma Suri), and "Saptatika" (by Chandrarshi Mahattaracharya or Shivsharma Suri).

- Modern Karmagranthas: Refers to five Karmagranthas compiled by Shri Devendrasuri, following the subjects of the ancient texts and are currently more prevalent in study.

- The book being summarized is "Karmavipak," the first in the modern series by Devendrasuri.

6. The Author and the Purpose of the Book:

- Acharya Shri Devendrasuri (author of the modern Karmagranthas) lived in the Chandrakul tradition and passed away in Vikram Samvat 1327.

- The author, Dhirajlal Dahyala Mehta, states his motivation for writing this commentary is to present the complex subject of Karma in a simpler language, building upon existing Gujarati commentaries, for his personal study and for the benefit of others.

- He acknowledges the contributions of previous commentators and institutions, including Shri Yashovijayji Jain Sanskrit Pathshala, Mehsana, and Pandit Bhagwandas.

- He expresses gratitude to Muni Shri Abhayshekhar Vijayji for his review and valuable additions.

- The book is presented as a guide to understanding Karma, its causes, and its effects, ultimately aiming to help readers achieve spiritual liberation.

7. Introduction to the Textual Analysis (Pages 20 onwards):

- The text then delves into the foundational aspects of Karma, beginning with the definition and nature of Karma Vargasnas (subtle matter particles that form Karma).

- It elaborates on the eight types of Vargasnas: Audarik, Vaikriya, Aharak, Taijas, Bhasha, Shvasochhvas, Manovargasna, and Karmanyavargasna.

- The initial four Vargasnas are gross (Badar) and visible, while the latter four are subtle (Sukshma) and invisible.

- The text addresses questions about how inanimate matter (Karma) can adhere to the Soul and impart suffering or happiness, drawing analogies to explain the interaction between the Soul's passions and karmic particles.

- It clarifies that the connection between the Soul and Karma is beginningless (Anadi).

- The text poses and answers fundamental questions about Karma, such as its nature, its origins, its binding principles (Mithyatva, Avirati, Kashaya, Yoga), and how it differs from other philosophical views.

- The initial verses of "Karmavipak" are presented, defining Karma and its four aspects: Prakriti (nature), Sthiti (duration), Ras (intensity/effect), and Pradesh (quantity). These are explained with the analogy of a Laddu (sweet ball).

- The eight main types of Karma (Gnanavaraniya, Darshanavaraniya, Vedaniya, Mohaniya, Ayushya, Nama, Gotra, Antaraya) are introduced with their respective subdivisions, totaling 158.

- The order of the eight Karmas is explained based on their impact on the Soul's core qualities (Jnan, Darshan) and their sequential unfolding in the spiritual journey.

- The text then begins a detailed explanation of the five types of Jnan (knowledge) in Jainism: Mati, Shrut, Avadhi, Manahparyav, and Keval Jnan, further breaking them down into their numerous sub-categories and providing analogies to clarify their meaning.

In essence, this book serves as a foundational text for understanding the complex and central doctrine of Karma in Jainism, presented in a scholarly yet accessible manner.