Jalpmanjari

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Jalpmanjari":

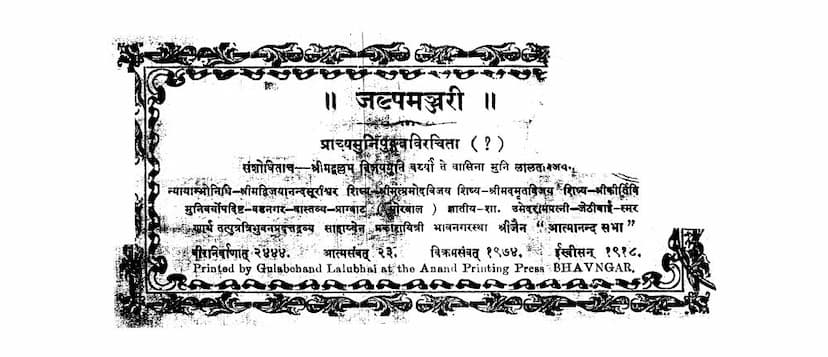

Book Title: Jalpmanjari Author(s): Pungav Prachya Muni (attributed), Lalitvijay (editor/compiler) Publisher: Atmanand Sabha Publication Date: Vikram Samvat 1974 (1918 CE)

Overview:

"Jalpmanjari" is a Jain text that appears to be a compilation or commentary, likely focused on philosophical and logical discourse. The title itself, "Jalpmanjari," can be broken down as "Jalp" (discussion, debate, argument) and "Manjari" (a cluster of flowers, a collection, a bouquet). This suggests the book is a collection of discussions or arguments, possibly related to Jain philosophy and logic.

Key Sections and Content:

The provided pages offer insights into several key aspects of the text:

-

Invocation and Dedication (Pages 1-2):

- The text begins with traditional invocations, paying homage to Jain Tirthankaras (specifically Vardhamana Jin) and revered spiritual guides (Suri).

- Page 1 indicates the publisher as the "Shri Jain Atmanand Sabha" in Bhavnagar. It also notes the financial support from the family of "Sha. Umadaram" and his wife "Jethibai," with the help of their son "Tribhuvandas." This suggests a philanthropic motive behind its publication.

- The publication date is given as Vikram Samvat 1974, which translates to 1918 CE.

- Page 2 contains a "Nivedan" (request/address to the reader). The editor, Muni Lalitvijay, expresses hope that the reader will accept this "unique gift" of the text and acknowledge the author's effort.

- Crucially, the editor admits that the original author and time of creation are unknown. He requests readers to provide any information they might have about the original author.

- The editing was done based on a single manuscript obtained from Muni Mahraj Shri Manvijayji. The editor acknowledges potential errors due to reliance on a single source and requests corrections.

- The publication was sponsored by Muni Maharaj Shri Amrutvijayji's disciple, Muni Maharaj Shri Kirtivijayji, in memory of his mother, Shrimati Jethibai, with the assistance of his brother Tribhuvandas of Vadnagar.

-

Introduction to Jain Philosophy and Other Darshanas (Pages 3-17):

- The text then seems to transition into a discussion of various philosophical schools (Darshanas) and their core tenets, likely as a prelude to or in contrast with Jain philosophy.

- Page 3-4: Starts with praise and questioning about the audience's knowledge, inquiring about their country, village, scriptures studied, and expertise in various fields like grammar, literature, prosody (Chhanda Shastra), and astronomy (Jyotish Shastra). It lists numerous grammatical treatises.

- Page 4-6: Continues the discussion on scriptures, delving into literary works and grammatical texts. It then introduces the six major Indian philosophical systems (Darshanas):

- Buddhist (Page 6): Describes Buddha as the deity, two pramāṇas (means of valid knowledge) – perception (pratyaksha) and inference (anumāna). Explains the three characteristics of inference (pakṣadharmatva, sapakṣasatva, vipakṣāsattva). Briefly states the Buddhist view of impermanence (anityata) and atomism.

- Nyaya (Page 6-8): Identifies God as Ishvara, the creator. Lists the sixteen categories (padārthas) of Nyaya, including pramaṇa, prameya, doubt, purpose, example, etc. It details the five members of an inference (pratijñā, hetu, udāharaṇa, upanaya, nigamana). It explains various fallacies of reasoning (hetvābhāsa) such as Asiddha (unproven), Viruddha (contradictory), Anaikāntika (indefinite), Kālatyāpadiṣṭa (belated), and Prakaraṇasama (balanced).

- Page 8-9: Continues the discussion on hetvābhāsa, explaining their sub-categories and examples. It also describes different types of sophistry (chala) and fallacies of argument (jāti).

- Sankhya (Page 12-13): Mentions that some Sankhyas believe in a God. Lists the 25 tattvas (principles) of Sankhya, including Purusha and Prakriti (with its three gunas: sattva, rajas, tamas). It defines liberation (moksha) as the separation of the soul from Prakriti. It states that all objects are eternal and that the means of knowledge are perception, inference, and testimony (āgama).

- Jainism (Page 13-16): Presents the Jain perspective.

- Deity: Jina.

- Core Principles: Jiva (soul), Ajiva (non-soul), Punya (merit), Papa (demerit), Āshrava (influx of karma), Samvara (stoppage of karma), Nirjara (shedding of karma), Bandha (bondage of karma), Moksha (liberation).

- Path to Liberation: Samyak Darshan (right faith), Samyak Jnana (right knowledge), Samyak Charitra (right conduct).

- Means of Knowledge (Pramāṇa): Two types: Pratyaksha (direct perception) and Paroksha (indirect perception). Pratyaksha is further divided into Mukhya (principal, e.g., Keval Jnana) and Sāṁvyavahārika (empirical, through senses). All other means (smaraṇa, anumāna, upamāna, āgama, arthāpatti) are considered Paroksha.

- Anekānta Vāda (Many-sidedness): The text strongly defends Anekānta Vāda, the Jain doctrine of manifold standpoints, as the solution to apparent contradictions found in other philosophies. It argues that seemingly contradictory qualities (like hot/cold, existence/non-existence, unity/diversity) can coexist in an object from different perspectives. It criticizes "ekānta vāda" (one-sidedness) as leading to fallacies.

- The text refutes the idea of mutual destruction (niṣedha) between opposing qualities in the context of Anekānta.

- Vaishēshika (Page 16): Identifies Shiva as the deity. Lists the six categories (padārthas): dravya (substance), guna (quality), karma (action), sāmānya (generality), viśēṣa ( particularity), and samavāya (inherence). Pramāṇas are perception and inference.

- Jaiminiya (Mimamsa) (Page 16): States they do not believe in God. Considers the Vedas as the ultimate authority (apaurusheya - not authored by humans). Defines Yajna (ritual) as dharma. Lists six means of knowledge: perception, inference, testimony (āgama), comparison (upamāna), tradition (aitihya), and absence (abhāva).

- Nastika (Materialism/Atheism) (Page 16-17): Believes there is no soul that transmigrates. Consciousness arises from the combination of the five elements (earth, water, fire, air, ether) formed into a body, similar to how intoxication arises from alcohol. They deny the results of merit and demerit.

-

Debate and Argumentation (Pages 17-22):

- Page 17: The text asks the reader to identify their own philosophical school, deity, guru, principles, dharma, and means of knowledge, and to list the scriptures they have studied.

- Page 17-18: Presents a five-membered syllogism (anumāna) as an example: "Fire is cold, because it is combustible." This is a deliberately fallacious argument designed to be refuted.

- Page 18-20: The "first party" (vādi) presents the argument and defends it against potential fallacies like Asiddha, Viruddha, Anaikāntika, Kālatyāpadiṣṭa, and Prakaraṇasama.

- Page 19-20: The "second party" (prativādi) refutes the argument, primarily targeting the fallacy of Kālatyāpadiṣṭa (belated or contradicted by time/evidence). The prativādi argues that fire being cold is directly contradicted by direct perception (pratyaksha) which shows it as hot and burning. It then enters into a detailed debate about the nature of heat and cold, cause and effect, and the role of divine influence (mantra).

- Page 20-22: The text then presents examples of self-praise and belittling opponents ("swotkarsha-paragarhna"), illustrating rhetorical techniques used in debates. It uses vivid imagery and metaphors, comparing the debaters to animals like lions, elephants, and snakes, demonstrating the aggressive nature of sophistry.

- Page 21-22: The text ends with a concluding verse that might summarize the overarching theme of the book, emphasizing the power of speech or argument, possibly within the framework of Jain philosophy.

Significance:

- Preservation of Knowledge: "Jalpmanjari" serves as a valuable resource for understanding the historical discourse on Jain philosophy and its engagement with other Indian philosophical schools.

- Methodology of Debate: The text illustrates the intricacies of Indian logic and debate, showcasing the structure of arguments, the identification of fallacies, and rhetorical strategies.

- Importance of Anekānta Vāda: The strong defense of Anekānta Vāda highlights its central role in Jainism for reconciling apparent contradictions and achieving a comprehensive understanding of reality.

- Editorial Endeavor: The editor's dedication to preserving and presenting this text, despite the challenges of a single manuscript and unknown authorship, is noteworthy.

In essence, "Jalpmanjari" is a significant Jain work that delves into philosophical debate, critically examines various darshanas, and ultimately upholds the Jain perspective, particularly its principle of Anekānta Vāda, as the most logical and comprehensive approach to understanding reality.